“I can concoct a special smoothie for you to help you quickly gain enough weight to outweigh Berenice," Melvin said. "Then you’ll have your title back and you’ll get to stay at Caldini’s forever.”

And suddenly, as if he had delivered the solution to a long-sought-after puzzle, a wash of light streamed over her face. She enclosed his small body in her two massive hands and gave him a squeeze that almost crushed his tiny lungs. “Melvin, you are brilliant!”

Caldini had explained to Olga that she would be housed until the end of the week, until she was to permanently leave the premises. Meanwhile, Berenice the Behemoth was an even greater success than Olga had been. The papers were bustling with stories of the public’s sheer amazement at unprecedented human capacities. People came in from hundreds of countries just to see her. And with each hour of success that Berenice had, Olga continued to fume with rage. This meant that Melvin had to work quickly. He was up late into the morning, swirling beakers, flipping through the pages of his medical journals in the amber candlelight, tasting and remixing, writing copious notes. Until the next morning he presented Olga with a beaker filled with an electric green liquid.

“Drink this. If my calculations are correct, it will make you gain up to two hundred pounds in just one night!”

“Oh, thank you Melvin, thank you!” And she snatched the beaker from his hands and guzzled the contents like a ravenous hippo.

Melvin had a hard time sleeping that night. He had wondered if the whole thing would work, and if it did, how revered he would be in the medical community. But if it didn’t, if it had somehow killed Olga, how miserable and wretched his conscience would be. He never admitted to feeling jealous of Olga’s fame, but he did wonder what it would feel like to be loved and recognized by a wide, respecting community rather than a public of peanut-throwing critics. If he succeeded, he would undoubtedly be hired by any practice he liked, regardless of his short stature. He would go down in history from Melvin the Miniature to Melvin Garland, Medical Doctor. He and Olga would live together in a small village and have many perfect children. The world would wonder how such a small man managed to have such a beautiful wife, and how he had magically transformed her overnight. He smiled peacefully as he dreamed.

The next morning, Olga opened her eyes and felt strange. She felt her lungs expanding fully, as if they were no longer pressurized by inches of fat and skin. She felt a tremendous new agility and energy, like she had been a happy, buoyant child again. She got up with surprising ease from her bed, walked over to the mirror, and seeing herself, screamed.

Melvin was awoken immediately by the scream, which echoed fiercely throughout the tent, and beyond. His small heart began beating very quickly as he ran to her. “What is it darling? Olga?”

She turned around and he saw her. His body filled with warmth and he began to tremble as he beheld her, in full stature, gleaming. She was another woman entirely. The most beautiful woman he had ever seen. It was as if her shell of blubber had melted away to reveal a perfect, golden core. Her cheeks were raised toward the sky, her arms long and elegant, her lips thin and fair. The hideous larva had transformed into a breathtaking butterfly.

And the butterfly screamed, “What have you done to me!”

She began to cry. And her tears were not tears of joy at her newfound beauty, but tears of rage. Melvin couldn’t understand. He had done it. He had figured out the world’s greatest diet elixir, and here Olga was, crying and crying that she was finally, miraculously, beautiful.

“Olga, why are you crying?”

“What have you done to me?” She repeated, more solemnly now, behind her sobs.

“I couldn’t let you gain any more weight. You were going to die. Now we can live the life we’ve always dreamed of, get out of this freak show and have a family. Isn’t that what you wanted?”

But her sobs grew so great that Melvin’s joy of his own success quickly faded to pity and fear for Olga’s transformation. She was so loud that she stirred the other performers from their sleep. After a few minutes of sobbing, Caldini came bursting through the tent with a flourish, his face flushed with pink. Caldini informed them that Berenice the Behemoth had been committed to the hospital and due to die any day now, and that Olga was to reclaim her title as the fattest woman in the world. “Where is Olga?” Caldini said. “ I must tell her! My business depends on it!”

Melvin gestured sadly to the woman by the mirror.

“That’s Olga,” said Melvin. “That’s your Olga the Oaf.”

Caldini was silent, and took in her silhouette from afar, stepping back in shock at the sight of the woman. “That’s not Olga,” he said, then whispered to himself, “That is a beautiful stranger.” At this, Olga turned, dewy-eyed, to see him. Caldini walked over to her slowly as she sniffled in her tears and looked into his warm eyes. Caldini brought his hand to his mouth as he observed her from every angle, like a new species of Olga. His face drained from pink back to cream. He grasped her newly slender hands in his and smiled brightly. She smiled back, letting out a delicate hiccup. “It’s true,” Olga said. “Look what Melvin has done to me.”

Upon hearing her voice, it was at last beyond a doubt.

Caldini cried, “Can it be, that inside such a hideous creature can lie such precious beauty?”

***

Revenues had never been as high at Caldini’s after Berenice had passed away. In fact, now the business was once again plummeting to its defeat. With health crazes going mad across the country, and no more fat ladies in sight, Caldini decided to nix the freak show business entirely and take Olga as his wife. She accepted and they had three children together. Melvin was despaired. Although he had succeeded at making the world’s greatest diet elixir and was hired by the finest hospital in the country as lead dietician, he could not bear to imagine Olga and Caldini living together, neither of whom would ever again be called “Freak.”

The End

Kaila Allison is a recent graduate of New York University. Follow her on twitter and find more of her work here.

Elle DioGuardi is an artist and photographer living in Boston, MA.

Olga McNaulty was the fattest woman alive. At one thousand eighty-two pounds, standing six feet, three inches tall, she was the star of Caldini’s Freak Show. Never before had Caldini acquired such remarkable revenues from travelers far and wide who were both delighted and disgusted by the mass of skin and limbs that was the wonder, Olga the Oaf.

Olga had come along at such a perfect time, too, because the very day Caldini was on the train to Seraville to declare bankruptcy on his show, he spotted the enormous woman seated on a bench at Gerard Street Station. The bench was invisible beneath her giant parachute dress, which gave her the appearance of floating. Caldini decided to get off the train, approached the woman confidently, and completed the deal.

The deal was that Olga was to be his main act, that she would get paid handsomely and fed the most delectable meals one could imagine.

Olga was reluctant. The reason she was at the train station had not been to become a circus star, but to kill herself. However, when Caldini’s train had approached she could not even muster enough strength to get up from the bench, much less to hurl herself onto the tracks.

Caldini was warm-eyed with dazzling teeth, which he flashed at Olga in order to seal the deal. Seeing her soften, he shook her swollen paw and said, “I better call a tractor to haul you out of here.”

For one thing, Caldini was right about the meals. They were plentiful and delicious. Olga would get used to a diet of five greasy rotisserie chickens, three pounds of rich baked beans, ten cans of creamed corn, and for dessert, fifteen fresh strawberry-rhubarb pies.

Olga’s first appearance as “Olga the Oaf” was on a sticky Saturday night in August. Caldini had her dressed in a red and white gown that he had masterfully quilted from his extra supply of old curtains, tablecloths and circus tents. To Olga, who had never been so pampered in her life, the gown was beautiful enough to wear to the opera. Caldini put curlers in her hair and applied thick red lipstick to her puffy lips.

“Stunning.”

People from all over the United States and Europe had come to see Olga the Oaf as she lay, elbow propped and flab jiggling, eating handfuls of grapes and bushels of bananas on her extra-large chaise lounge. It was terrible at first, seeing the gawkers, the children. Olga had been in hiding her whole life, and now she was as on display as one could ever be. In her timidity that first night, she tried to be polite; not to belch, not to roll over in too unflattering a way, but Caldini coached her that the public didn’t want “polite.” They wanted to see Olga the Oaf, and Olga the Oaf they would get.

Olga’s reviews were astounding. Every paper had a picture of Olga on the front cover, with such headlines as “Caldini’s Back in Business, This Time with Heifers!” and “World’s Fattest Woman: Someone Give Her a Pie, or Ten.” Compared to what Olga was used to, these media insults were merely Grade One, and she took no offense by them. On the contrary, she was flattered by the existence of such sudden attention, and even more by the volume of it. Scientists came from the top universities to measure her dimensions, to give her blood tests, and sample her urine and DNA. Writers would sit in corners crafting stories about her. Artists would draw her, filmmakers would film her, musicians would serenade her. In return, Olga indulged them by posing with a giant Viennese sausage in her mouth, and they loved her. They whistled and they hollered for more. Olga thought that perhaps she had made the right choice after all. She would soon belch without hesitation, scratch herself and jiggle the fat of her arms freely. The audience roared in excitement. They loved the speckled white lines on her stomach and legs, her purpled dinosaur feet, her majestic flapping ears. And by the end of the first week, she thought that if it hadn’t been for Caldini, she might have made the foolish decision of killing herself.

Although the train incident had not been her first attempt at suicide. The first attempt was when Olga was twelve years old and told that she was not allowed to go on the field-trip to the hospital because there were no scrubs or lab coats large enough to fit her. At this point she had been a mere four hundred twenty-nine pounds. That night at home, she had fastened her belt around her neck and attached it to the ceiling fan in her bedroom, but upon descent, had only succeeded in ripping the ceiling fan out of the wall.

Olga’s lodgings at Caldini’s were modest, yet comfortable. She was housed with another of Caldini’s performers, Melvin the Miniature, in an extra-large tent. How they met was by Olga almost sitting on him after her initiation meal. She heard a voice small as tin screaming, “Don’t sit,” and they became instant friends.

Olga and Melvin exchanged their stories by candlelight. Olga told Melvin of the days of her merciless playground tortures at school, to which he could relate. How the kids would see in a test of strength who could push Olga over from a standing position. No one ever succeeded, even from a running start. Melvin’s torture came from being the designated fetcher of lost gymnasium equipment that had retreated to unreachable playground nooks. He was never allowed to play in the games. Olga told Melvin of sixth grade sex-ed, when Jerry Barnabie said, “I bet her vagina’s the size of a watermelon.” Melvin told Olga of his tryouts for the baseball team, when the Coach Carl said, “Are you trying out to be the ball?” They laughed together and they cried together. They both had no family left, and little hope for a family in the future. They also both had dreams.

Melvin had always wanted to be a doctor, fascinated by the wonders of the human body since an early age, when he would analyze the organs of dead animals his father brought back from hunts. Naturally, he took an interest to the never before seen bone structure and asymmetry of Olga’s body. He wondered how much her heart weighed, the fat content of her liver, the functionality of her reproductive system under the stress of gravity. He would scribble observations in his notebook while watching her from afar. Olga told him about her failed field- trip to the hospital and she became sullen. She said all she wanted was to have a legacy, and now it seemed for the first time, possible.

For three months Olga enjoyed her constant fame at Caldini’s. She was witty and found a profound pleasure in being looked at. She was invited to parties and conferences along with the other most incredible freaks of the world, among them Fern the Fertile (who gave birth to forty-two consecutive children) and Peter the Pin-Faced (who had stuck three-hundred forty-nine pins in his face). Yet Olga never ceased to charm the crowd. Special ten-course meals were served to her as she sat comfortably in her custom made chairs. She received constant letters and requests for autographs. Some even asked her to belch for them. Back in her tent, she would spend hours in front of the mirror puffing out her cheeks and tripling her chins, while Melvin would be curled on his miniature dog-bed around a book twice his size called Gray’s Anatomy. Melvin thought about Olga, and how she was the first woman who voluntarily talked to him. His first real friend, and not a sympathy friend, but one with genuine care. He remembered the night he swore he fell in love with her.

It had been after the mid-season festival, when both Olga and Melvin had been fully inebriated (Olga with forty-eight shots of whiskey and Melvin with half a glass of wine), and Olga had plopped on the bed and asked Melvin, “Do you ever dream of having children?”

“I think everyone does at some point. Don’t you?”

“I dream about it all the time. Just imagine, little fat cows running around the house! And they can all be their own stars one day, just like their momma.”

Melvin gave Olga a loving glance. “I wonder, Olga, if I may ask you a question. Do you know if you are...fertile?”

And to this she snapped up, jiggling, and smiled. “We could find out.”

Melvin was entranced in his reverie while he read Gray’s Anatomy beneath the warm amber glow of candlelight, peeking over at Olga’s nightly repetitions as he went to turn each page.

“I am the fattest woman alive,” Olga whispered to the mirror.

Until one day, she was no longer. The news came to Caldini on a Saturday in November. Another woman, Berenice the Behemoth, had just been discovered in Alabama, weighing in at one thousand, two hundred twelve pounds. At a full one hundred thirty pounds heavier than Olga, Berenice was the new fattest woman alive. And as soon as Caldini put down the phone confirming the news, Olga was stripped of her title, and plans were arranged for Berenice to be shipped in.

Olga was told that she was being let go, that Caldini didn’t need her anymore and that she should go back home and make something new of her life.

That afternoon, Olga stomped into her tent in a fury, causing Melvin to bounce up from his dog-bed, and his book to flutter to the floor with a thump.

“But I don’t want to make something new of my life!” She screamed.

Melvin gathered his book and laid it on the nightstand. “What is it, Olga? What are you talking about?”

In an attempt to cross her arms in fury, they only came, tragically, halfway around her stomach. “Have you heard of this Berenice the Behemoth?”

Olga plunged face down onto the bed, crying, making it creak and bounce loudly. Melvin jumped up next to her, bringing a hand to her hot, wet cheek. He couldn’t think of what to say to console her, so remained silent.

“No one cares about the second fattest woman alive!” She bellowed.

Olga attempted to turn herself around to see Melvin’s reaction, resembling a pot-bellied pig burrowing into a mud puddle. He looked contemplative.

Melvin had grown so close to Olga in these past few months that he hadn’t been prepared for such a hasty departure. But he also knew that Olga was going to die soon, that there was no human way her heart could support the stress of her massive body - an inevitability he purged defensively from his scientific mind. But this inevitability he had understood, nonetheless. Olga was against dieting. She thought it was a fad that was only for the obsessive teenage bullies of her youth. And every time that Melvin told her to watch what she ate, to limit the bad carbs and greasy fats, she had rolled her eyes at him, saying, “What’s another couple’a pounds?” He had been experimenting late at night with weight-loss potions and elixirs, and thought Olga was in a state helpless enough to agree to be his test subject.

“I have an idea,” Melvin said.

To be continued...

***

Kaila Allison is a recent graduate of New York University. Follow her on twitter and find more of her work here.

Grandmother let me help her set the table. Billy pulled out the leaf to make it bigger when there were lots of people. "We will use the linens for the guests — our best tablecloth, Ellen."

I enjoyed polishing the silver with the bluish cream and the soft blue cloth. She set up my work shop on the porch at a table covered with newspaper. This way I could smell the ocean, hear the seagulls squawking, and watch the boats going by. I counted the boats, forgetting to work.

"She's dreamy, Esther," I could hear her telling her sister in whispered tones on the black phone in the kitchen. I could imagine great aunt Esther saying something creepy about me. Mommy used to turn up her shoulder when Aunt Esther came to town. She had the same look when we ran into Mr. Wicker, her boss at the bank, when we met him at the grocery store . "Mr. Wicked" was her name for him. She said that to her friends in her quiet voice.

I remember only pieces of the day it happened. My neighbor Sarah, in the middle of balloons the scary clown was shaping into animals. I snuck an extra piece of cake when nobody was looking, as sugary treats were new to me. When I saw the policeman talking to Sarah's Mom, I thought I was in trouble for my theft. His big hand felt like sandpaper as he guided me to the fancy living room where no kids were playing. Sarah's Mom stood behind the purple chair, it's edge too plump for her fingers.

I do remember my grandmother coming to Sarah's to get me. Policemen held on to her and the clown bumped into her. "Accident. Hospital. Heaven."

I think I heard those words, or maybe learned them in the meetings I had with the nice lady who lived near grandmother. In the year since it happened, I saw the lady a lot. "Ellen" she would say to me, when I couldn't look at her, "Tell me how you feel." I loved Gam so much, I was afraid to tell the lady how sad I was. How much I missed Mommy.

The day my grandmother agreed to a nickname was sunny. We had come to the porch to play cards and watch the ocean. "Gam. I want to call you Gam," I said, looking at the ocean. She pulled back her lower lip and said. "Ellen, Gam it shall be!"

Gam turned little things into a celebration.

"How many flowers are on that tree?"

"Who cares if the recipe says cinnamon? No need sending Billy out for that."

Billy lived next door. One of the Gilligans. They had a lot of kids. He went to a special school. Gam paid him for the chores she needed done since Grandpa died. Gam's voice changed when Billy was around. She left spaces like Reverend Miller did after his stroke.

Gam and I brought dinners to the Millers. She would leave them on their doorstep. She let me clang the hanging bell on the door as a signal. Even though Gam was sad Reverend had to retire, she still played word games with me on the sandy road to their cottage.

"Let's pick new names for everything we see, Ellen."

"The gifts of sight and speech ... and your imagination. Use them! Enjoy them!"

Miss Dixon didn't like Gam's games. She called Gam into school to meet with her. I wasn't allowed to go, but I knew it wouldn't be fun. Miss Dixon didn't like fun. Or me.

"Esther, she wants her to color between the lines," Gam said, not bothering to whisper.

I was kind of confused because I was good at coloring. Even Miss Dixon said so.

Then Gam started whispering again. I tip-toed through the hall, careful not to step on the noisy floor board.

"Not one word of sympathy about my Julia. Nothing." Gam got quiet. I think she was crying. Julia was Mommy. Oh how I missed Mommy! I stood still as a statue. Mommy used to be little like me. It was hard to picture Mommy jumping rope or coloring.

I wanted to ask Gam all about Mommy, but I didn't want to make her cry, like Miss Dixon did. But Miss Dixon didn't ask about Mommy. I knew that made Gam sad. Everything about Mommy made us sad.

The next day I asked Miss Dixon if she liked my coloring.

"It's good, Ellen. But we're doing subtraction now."

When we got to poetry, Miss Dixon told me to sit down and study it better. I had said sparrow for bird and violet for purple. I remembered that Miss Dixon wasn't Gam.

That evening Gam and I played cards on the porch. The waves were big and loud, and the birds were squealing like crazy. Gam lifted her tea cup and smiled at me."I dropped off the peach pie we made to the Reverend today. Mrs. Miller told me she didn't feel up to planning a birthday party for him. I'd said we'd do it, Ellen."

Just then, a big white bird landed on the porch railing. It was as big as me, and had a pink tail. "Our first guest, Ellen! A spoonbill!"

After Gam read me a bedtime story, I crept over to my encyclopedia, to look up spoonbill. It wasn't a made-up name. There was a pretty picture of it. I needed to get things straight for Miss Dixon.

Gam walked me to the Millers more than usual, to ask about the party.

One windy day, we passed Danny Gilligan, Billy's older brother, opening the car door for his mother, just like the movies. He wore bright red sneakers that came up to his ankles. They had a white star near the top.

"I wish I could drive a car. When I get bigger, I will."

"Don't wish your life away, Ellen. There is a time for everything."

"No ... church ... people, " Reverend said to us. Mrs. Miller's face got red like mine when Miss Dixon corrected me. "He doesn't want to exclude anyone. Or make you work too hard," she said to Gam.

"Then we'll have a small luncheon. We'll invite the Gilligans and my sister, Esther."

Oh no, I thought. Aunt Esther could ruin anything. Later that evening, I was happy to hear Aunt Esther couldn't make it. Then I felt bad because she was Gam's sister. And Mommy's aunt.

The day of the party was sunny and bright. Billy came over early to pull out the leaf to make the table big enough. Gam and I put on a light brown table cloth with pretty yellow flowers.

I folded the linen napkins and placed the silverware I polished where Gam had taught me.

Billy opened the windows. He had put in the screens earlier that week.

Gam and I baked a big square birthday cake for Reverend Miller.

The Gilligan family were our first guests. I was disappointed that Danny couldn't come. His Mom said he had to work. Danny was nice to little kids. Billy told me Danny's job was with kids, when he wasn't in school.

Mrs. Miller pushed her husband's wheel chair up to the table. She asked Gam to sit down and relax. "You've done enough. Sit down and enjoy this fine food," she said.

We said grace and began to eat. There was a knock on the front door. Billy answered it.

I noticed Danny's sneakers as he walked into the room. He had a big red bulb on his nose, and a costume like a clown. I thought of the clown the day Mommy died, but remembered it was Danny. He said hello to everyone and waved his squirt bottle.

Gam screamed and pushed away from the table. She let out a sob so loud, it nearly broke my heart. Her shoulders shook as she put her hands to her face. "Julia," she said through her hiccups.

Mrs. Gilligan led her family from the table. Mrs. Miller put her arms around Gam.

"I'll read you a story, Gam. I'll make you tea," I said.

Mrs. Miller looked over at me, and I knew it was time to be quiet. I listened to the noisy seagulls outside. I made up stories that they told each other. Stories I would tell grandmother later, when her shoulders stopped shaking.

I could picture Gam in her porch chair smiling, drinking tea, sitting up straight and still.....still, like the spoonbill who visited us before the party.

Edith Gallagher Boyd is a graduate of Temple University. She lives in Palm Beach County, Florida.

"There is so little light, from the warmth of the sun" - Outside, Digging by James Vincent Mcmorrow. Accompanied by: Adam Melchor This song is for the brown boys. Those who have been victim to police brutality, those who fear it, and those who have yet to be born.

Amy Leon is a an actor, poet, singer, and Harlem Native. She recently graduated from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts and has been leading her life as a full time creative mind ever since. She recently self-published her first collection of poetry, the water under the bridge, and is currently on the Nuyorican Slam Team. She just returned from her first European poetry tour and is happy to be back in NYC! The mantra: Love loudly, Give quietly, Listen always.

(via Soundcloud)

Amy Leon is a an actor, poet, singer, and Harlem Native. She recently graduated from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts and has been leading her life as a full time creative mind ever since. She recently self-published her first collection of poetry, the water under the bridge, and is currently on the Nuyorican Slam Team. She just returned from her first European poetry tour and is happy to be back in NYC! The mantra: Love loudly, Give quietly, Listen always.

First single from jazz/hip hop songwriter and storyteller, Elbows, featuring raps by Brooklyn emcee, SKRD. Home LP coming Fall '15.

Elbows is a Brooklyn-based jazz/hip-hop storyteller. His first LP, Home, is coming in the fall.

This is my protest. Because brown. Because black. Because innocent. Because unarmed. Because child. Because father. Because human.

Amy Leon is a an actor, poet, singer, and Harlem Native. She recently graduated from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts and has been leading her life as a full time creative mind ever since. She recently self-published her first collection of poetry, the water under the bridge, and is currently on the Nuyorican Slam Team. She just returned from her first European poetry tour and is happy to be back in NYC! The mantra: Love loudly, Give quietly, Listen always.

Yes, Officer, I - I know, that is, uh, I’m fully aware of all that but–and this is kinda hard to explain–it doesn’t take into account our sexual problem. Well, more accurately, uh, my sexual problem because in all honesty it’s my problem and not some shared–not hers and mine together. It’s just my ego and her politeness that made it “ours.”

See Officer, my problem was, uh, a real relationship killer until I met Her. Not many women can handle the odd intimacy neurosis – let alone what I suffer from – but She could, which, uh, I guess is really the worst part of this whole fiasco. ‘Cause now, whatever happens, I don’t have that sort of accepting partner to “come home to” as it were. Though it’s a bit discomforting at the same time now because, uh, I’m wondering if that was all that kept us together. My problem, that is. We didn’t have a whole hell of a lot in common –

Hmm? Oh, sorry. I get off in tangents, just feel free to interrupt me. But anyway, getting back to my problem...

I’d like to point out I am not a pervert, despite how this may all sound. I just, uh, have desires and whatnot that, let’s say “differ” from the vast majority of people. See, I can’t really get off when I’m with a woman without following a, uh, pretty complex procedure. You’re probably thinking this would cause me some problems and you’d be absolutely right. Not many woman – well, people – are willing to accept some minor “kink” and I’ve got one, uh, hell of a “kink” thing. Used to be I wouldn’t even bring it up until later in a relationship and that was just really uncomfortable. I was actually with this one woman for, uh, about a year before telling her. A – a whole goddamn year – year of faking orgasms and jerking - off in the shower. That’s no way for a man to live, Officer.

I know... I’m getting to it...

My problem is essentially this: First, uh, I need my significant other to run naked around the bed sort of like an ostrich – her arms straight down and legs kicking out behind – while I, uh, lie on the bed and masturbate. Then, she has to crawl on top of me and say in as deep a voice as possible “I am the walrus!” and I, uh, respond “Coo - coo - cachoo!” It’s this call and response thing and we do it a few times –

Please, Officer. As I said at the very beginning, I’m no pervert or monster. I just have, uh, tastes that may differ from you or other people. A Coke or Pepsi sort of thing. Besides, I wasn’t finished...

So, up until this point I’ll, uh, venture to guess most women would be willing to play along, even if they thought it was, uh, kind of silly. See, the part that turns most women off is what comes next. I don’t suppose you were, uh, there or you heard – Oh, you weren’t? Didn’t hear about it? Uh, okay, then. This may be a bit hard to explain...

You see Officer, I use this special harness – or swing, I guess – to get both the woman and, uh, myself in the right positions. I actually had to make it myself, you can’t buy it anywhere. Well, you can buy plenty of “sex swings,” but nothing that would really, uh, fit. Do you see what I’m saying?

So, basically the, uh, harness holds my partner and I together in, you know, the normal position – I mean, uh, missionary but not really. We’re kinda joined at the hips, you know, but suspended in the air, sort of. Now this – this isn’t the actual sexual problem.

See, Officer, I can’t climax unless my partner is suspended in the air with a rope tying her arms back so they’re, uh, sort of looped. Now, what I do, see, is slide my arms through hers, like so, so I can reach the rope and, uh, pull myself into... you know, the whole thrusting thing. I know it’s complicated, but what works, uh, works.

So, this time – as in right before I was brought here, Officer – I was having some trouble and just wanted to finish for her sake. I’m not some deviant sex fiend, you know. I respected her as, uh, a human being.

– Now I should, uh, explain something here: The harness has this part that loops over my partner’s neck. No, no, it’s not a noose or anything, just enough to arch her back and – really, it’s, uh, integral to the whole slipping-my-arms-through process and never intended as some form of autoeroticism or whatnot...

So this particular time, when I’m having trouble, I start pulling on that part of the harness–which, honestly, doesn’t even go all 360º around her neck so it cannot be considered a noose, you know... I start pulling myself more into the thrusting to get more out of it and finish and I finally, uh, orgasm and I think that’s when it happened because I yell “choo-choo” really loud when it – my orgasm, not it – when it happens so I probably didn’t hear the, uh, snap...

Officer, I know what you must be thinking. I mean, uh, I’m aware of how this sounds – I’m a degenerate, I’m a horrible person, yadda yadda – you know, it’s not like I don’t think these things of myself. Oh, not because of my sexual problem, I’m perfectly fine with all that. It’s just that she’s not, uh, “here” I guess is the thing...

Trevor Kroger is an independent author and scholar residing in Brooklyn, NY. His novels Fiend and One Nation Under God are available onAmazon and Smashwords.

(via Bandcamp)

Amy Leon is a an actor, poet, singer, and Harlem Native. She recently graduated from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts and has been leading her life as a full-time creative mind ever since. She recently self-published her first collection of poetry, the water under the bridge, and is currently on the Nuyorican Slam Team. She just returned from her first European poetry tour and is happy to be back in NYC! The mantra: Love loudly, Give quietly, Listen always.

Pay No Mind

Pay no mind to the fishing boats, the seanight must swallow them. The fisherman will still send us the sadness locked in his calloused hands. Hidden in the stinging wind, and marching with the drowning waves.

And if you must call out to him, wring your hands and wail some new song, some untold melody. For the solitude and the tides and the gasoline have almost deafened him.

Pay no mind to those stars there. They are relics, they have nothing new to say. I will ask them their ages. I will translate for you.

And if you pulsate, if you must radiate your own cosmos, turn off all of the lights above and whisper it to me.

And those pebbles you pass between your toes, pay them no mind either. They are weary from their travels and wish only to rest here on the shore.

But if you must ask them where they have been, lay down your head on my chest and let my aching breaths fill the gaps of their stories, between wavebreaks, for I know them well.

And my tears now that come, pay no mind to them. No, not when there is all this. Count the wave crests. Let the mist paint with you and the moon. I would swirl his grays and your oranges.

But if you must ask, I weep for you to join me. For the sea to somehow spill me into you, like the breakers flood the tidepools. For it to crash upon you with my cyclones and my surges, for it to devastate you with me. As you have broken me, your onslaught.

And then I could love again. The stories of the pebbles . The secrets I have for stars. The lights on fishing boats.

Did It Rain

Did it rain the night I watched the candlelight pour over your shoulders and collect like honey in the bowls of your collar bones?

And softly you sang to tomatoes all of the notes that will stay locked in my skin, harbingers of your songs.

Seeds

and red pith.

Persimmon shades over

bones and melodies.

Did it rain the night your eyes made the dark a fortress of my quickened breaths and my threadbare lips?

And softly you kissed my eyelids and made of them shields to bear away my rasping heart.

Fires

burned and burning.

Your mouth

names me

to ashes and coals.

Did it rain the night when I needed stars and winds to hold me, like the guardians I have made them to be?

And softly the clouds hung there, and with compassion they painted my blood a wonderful bluegrey.

Droplets

and cloudbursts.

Cinereal condensation

on my windowpanes.

Did it rain the night I knew I had lost your treacle-sweet taste, and the clamor of your touch?

And softly you left me, as raindrops fall from the lamina of young birch leaves. Silent and penitent, to the drifting brook below.

Rain

through my palms

over knuckles

fallen away.

John Rossi lives and works in Brooklyn, and is inspired by angry train people and humanity in general. He works in event production, and travels the country plying his trade at various film and music festivals.

A visualization of one's struggle to find comfort and beauty in the skin she's been taught to fear. OFFICIAL SELECTION OF THE 2015 LANGSTON HUGHES AFRICAN AMERICAN FILM FESTIVAL. Directed and Produced by Matthew Puccini and Tyler Rabinowitz; Original Poem by Amy Leon; Cinematography by Matthew Puccini; Edited by Matthew Puccini; Production Design by Tyler Rabinowitz; Sound Design by Rom/Toby.

Amy Leon is a an actor, poet, singer, and Harlem Native. She recently graduated from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts and has been leading her life as a full time creative mind ever since. She recently self-published her first collection of poetry, the water under the bridge, and is currently on the Nuyorican Slam Team. She just returned from her first European poetry tour and is happy to be back in NYC! The mantra: Love loudly, Give quietly, Listen always.

I had seen him before, doing crotch-tearing splits in the middle of our only pedestrian street. Burlington, Vermont is a city of enigmas; there is Kornbread, rapper, coke dealer and impromptu comedian; Birdman, with his gaunt face and oversized sunglasses, known for wheeling around a stolen grocery cart filled with spray painted trash; there’s the fat widower who parades through town wearing lopsided heels and a dirty tutu—a thick, Joker-esque line of lipstick demarcating his mouth; there’s the seven foot schizophrenic that cups his balls over his sweatpants and mumbles profanities to passersby; the regal Jamaican who hangs out in front of the kabob shop with his massive bouquet of dreads and gnarled walking stick; the crust punks with their two liter Sprites and gaggle of leashed cats; the obnoxious seasonal accordionist; the court jester with the ladder; the masked didgeridoo player; the slow-walking, Bangladeshi monk; then there’s Karl.

I met Karl at Starbucks. The normal demographic of imitation hipsters and basic bitches that Starbucks typically attracts is upset by Burlington’s homeless population—those who order a single black coffee and use that as license to stash their three trash bags full of clothes and fold-up mattress in shop. Karl is one of these squatters. He has been coming to Starbucks for so long that he has laid claim to one of the tables on the far right by the window. He has pseudonymed this table his “desk.” I tended to sit at the table adjacent from his, by pure happenstance, often because it was the only one left unoccupied. It was at that table that I had my first real encounter with Karl. Karl was a point of intrigue: a case study into the surreptitious underbelly of Burlington that I had always hypothesized about. In my experience, it is not abnormal for people to demonize the homeless: to make up narratives about them that they are lazy and weird and dangerous and underserving of a few bucks and a friendly hello. It seems that more often than not, there is a necessary dehumanization that defines our interactions with homeless people. Moreover, it is easier for people to deny their humanity than to confront the guilt that would come with treating them as equals. I have always been saddened by this reality, by our survivalist, self-preserving approach. Maybe that explains why when Karl struck up conversation with me, I did not write him off or debate changing tables: I listened.

***

“You know who I am?” he whispered.

Karl removed the black Beats by Dre from around his neck and stared at me through translucently rimmed glasses. I looked down at his hands resting on the white marble table. His knuckles were scabbed, clad with turquoise rings and charred from cigarette ash.

“I don’t believe I do,” I said, quietly anticipating his answer.

“I’m a writer. I’m a poet. Sometimes I’m a dragon. I’m whoever I want to be.”

There was a lubricative quality to Karl’s voice; his delivery was smooth and free flowing, slick as black ice. One could appreciate his bravado. In seconds, he grabbed a rogue chair and scooched closer to me to tell me about the book he was writing.

“It’s called Bending Steel. It’s a lil’ somethin that’s never been done before. Never before in history, I don’t think. Lemme tell you, honey. I went to four jails and visited inmates. I recorded their stories and I did this crazy thing. I made poems out of them.”

I told him I liked the title and the concept, unsure if my reaction was adequate, too cavalier.

“Ain’t nobody gonna read shit without a good title, cept course’ if they forced to. You in school?”

“I am in school, studying English…hopefully graduating in May.”

Karl cocked his head back and smirked, like I had just said something whack.

“You’re what…?”

“Studying English…?”

“That’s right! And I’m so glad you said that, cus now I know we’re gonna get along.”

And we did. From that point on whenever I’d run into Karl he’d give me a wry smile and extend his arm for a fist bump. He told me about his peripatetic lifestyle: his years on the gum-covered streets of Harlem, the heroin binges, the jail time, the gentrification, his eventual relocation to Vermont. He spoke in bullet points, but I wanted specifics: the full, uncensored story. I was a writer, moved by a magnetic inquisition. Karl was a writer too. We had that in common. Yet, it seemed as though the particulars of Karl’s life came second to his art, to the now. He knew who he was and didn’t need to go outlining that for people. And because our friendship was nascent, albeit foreign, I remained judicious. As much as I wanted to probe Karl about his past, I couldn’t shake the politics of race and social class that made my harmless curiosity feel like an act of condescension. I didn’t want to play ethnographer, but it felt like no matter how I engaged with Karl, that was what would come across.

Karl was conservative with his words. He spoke through actions; one time in October he handed me a melty, broken Butterfinger wrapped in a napkin. I unfolded it to find: I think I like you. You get me, written in messy cursive on the inside of it. I turned to Karl who stuck out his brain-pink tongue at me jokingly and left to go dance in the street. Karl moved like a limbless being. He exited buildings like a cephalopod.

After about a few days into our friendship Karl calmly ordered me to friend him on Facebook. He had a lot of friends (over 3,000), a figure he prided himself on. I deleted him a while back because he kept crowding my newsfeed with scantily dressed women, horoscope advertisements and Candy Crush invitations. Gauging from our pleasant exchanges following the deletion, I don’t think he has noticed the minus one.

A few weeks later I ran into Karl again. He was wearing a white button-up, Nike High Tops, a backwards hat and ratty suspenders. He is probably one of the only middle-aged men I know that looks natural in that street wear. As soon as I got closer to him I realized he had a monstrous black eye. His legs were bruised like a maltreated apple and one of his arms was in a sling.

“Karl, what the heck happened?” I exclaimed.

“Girl, six guys beat the shit out of me because I tried to cash a fifty-dollar bill at a convenience store. I woke up in ICU and I’m all SHOOK UP!”

“I’m so sorry man, that’s awful.” I didn’t know what else to say. Karl didn’t want my pity. He didn’t want to be seen as a victim, but my prescription was telling me otherwise. Why did this sting? What was the problem? I looked back at Karl leaning against a storefront window and wondered how he was seeing me, if he too was seeing archetypes…power. I felt naked. I didn’t want him to see the white girl, the student, the you-have-it-so-easy kid.

“Look, I’ve been shot twice, stabbed in the back, kicked down, socked with brass knuckles, backhanded with a frying pan, slammed against the hood of a cruiser…this is kids stuff. It’s crazy bein’ black in Vermont…bein’ black anywhere. I’m tellin’ you lady, it’s going to be the little shit that kills me. I’ll slip on a banana peel tomorrow or choke on my own spit and croak. ”

“Damn, Karl. From the sounds of it, I’d say you were immortal.”

“I’m not immortal, girl. I’m just Karl.”

***

Karl was like no one I had ever met before; he was groovy and earnest and incredibly unpredictable. With each interaction we had, I got to piece together a little more of his narrative. The interest was mutual. Our passions were too.

“Hey, go online. I want you to see something.”

Karl liked showing me things online: articles, mind-blowing images, and by and large, things that had to do with him. Karl was not a narcissist by any means. He was just extremely proud of his work and eager to share it with people.

Karl commandeered my laptop and pulled up his profile on some random poetry database. The website had ancient graphics that resembled pop-up spam. He gave the computer back to me and asked me to scroll down the page.

“Look at that. What’d I tell ya. I’ve written over 750 poems and I’m not quitin!”

He proceeded to recite one of his favorites, Dear Daddy, about the childhood death of his father. I listened attentively to each verse, watching precarious tears loiter in the crevices of his glassy eyes:

From the day of conception, my daddy was dead.

No man to man talks and the truth was not said.

To lead my life without his teaching or guidance,

But, I figure my voice, so I could not be silenced.

Karl had heart and so did his poetry; it had a pulse. And knowing that made it so much harder to acknowledge that the probability that it would leave his ratty notebooks or the outskirts of the Internet and be published—printed on glossy pages with his name on it and sold in Barnes & Noble chains nationwide—were next to none. I heard my privilege in his recitation, echoed back at me like a cave-scream.

“Thank you so much for sharing that with me. That’s a really impressive body of work. I hope I can get there someday.”

Karl let out a raspy laugh, flipping through the pages of one of his frayed composition books.

“He that lives upon hope will die fasting. Benjamin Franklin said that, I think? I’ve done so many fucking drugs I could be misquoting. Shit…Anyway, don’t hope, just do. You gotta’ start writing, girlie.”

The last time I saw Karl his face was wrapped in gauze; he told me that he was going blind—that he had already started to. He had multiple sclerosis: an often-debilitating disease of the central nervous system. Throughout my four years living in Vermont, I had passed Karl on the street on a daily basis. And despite his constant presence in my life, I didn’t really understand him for who he was. And in this way, there was something darkly ironic to his diagnosis—that just as Karl was beginning to loose his vision, I was truly beginning to see him, to individuate him as someone real and complex, someone that transcended his three, preassigned adjectives: unknowable, flexible, homeless.

***

“I’m goin’ down to New York next week to pick up my guide-dog. And ya know what, honey?”

“What, Karl?”

“They better give me a fuckin’ Doberman."

Elena Robidoux is a writer of prose poetry and creative nonfiction from Boston. Her work has appeared in Pulp Metal Magazine, Wu-Wei Fashion Mag, Potluck Mag, Purple Pig Lit, and Jerkpoet.

Before we got married, my wife and I spent most of our dating time riding around in my car, the yellow Firebird I inherited from my maiden aunt. We’d drive the hills and back roads around Knoxville, TN, back in those days when gas cost lest than $1.50 a gallon. We were students, a label synonymous with poor. She was in Human Services and I in English, career paths that were much straighter and more predictable than the roads we drove. On these drives we talked, held hands, got to know each other. I was a native of small-town Alabama, she, a native of big city Tehran. That’s Iran. Iran before the revolution. She got out just before the Islamic regime clamped down. It turns out that we arrived in Knoxville the same month of the same year: July 1979. Our fated road.

When I felt sure that she’d say yes if I asked her to stay with me forever, I planned a date to an intimate restaurant somewhere in the wilds beyond Lenoir City, fifty miles outside of Knoxville. The restaurant was run by a husband and wife team, and I had been there exactly one other time for a deliciously unorthodox meal. I remembered the way, for one benefit of driving backroads for fun is learning various routes. So on this evening, bottle of champagne in tow, the ring my parents had fashioned from diamonds in my mother’s family comfortably resting in my pocket, we drove. And when we arrived, the one flaw in my plan made itself clear.

The restaurant was closed.

Why it never occurred to me to call for reservations, or at least to learn of its operating hours, I can’t say. Maybe it was just that I was in love. Doesn’t that answer all seemingly useless questions?

How many people would have gone catatonic at this development? Lapsed into despondency? My soon-to-be-wife, however, looked at life both then and now as something to be entirely enjoyed. So she did what she always does in such moments: she laughed:

“Oh well. What do you want to do now,” she asked.

So I did what any sensible guy in love would do. I reached into my pocket and gave her the ring. Then I opened the champagne and we drank richly, straight from the bottle.

She wasn’t surprised by my offer, though I think the beauty and history of the ring took her aback. We laughed and kissed and enjoyed another unusual moment in our history. And then we drove back to Knoxville and ate dinner at an Italian place on Kingston Pike: Naples. I ordered a peppered shrimp dish for us, and we shared another bottle. I drove her home afterwards to her parents and returned to my basement apartment.

We got married a few weeks later at the Knoxville courthouse—in back of the courthouse actually, in a maintenance tool shed. The man officiating was called The Bishop. He looked about eighty.

And drunk.

He couldn’t pronounce my wife’s name: Azadeh. After he mispronounced it three or four times, she asked if he could just go ahead and pronounce us. This relieved him and he did as she suggested, a good move I’ve come to learn. I gave him $5.00 for his trouble, though he asked for ten. Ten was all I had, though, and I was saving the rest for a glass of champagne. We left the shed happy, even delirious, and certainly married.

The one thing about us that marriage didn’t altar a bit was our love of driving. So on many nights that summer after our wedding, we’d get in my car and drive a circuitous route talking and listening to the radio. Bruce Springsteen was big back then. You know. “Thunder Road” and other assorted gems.

We’ve been married now for over thirty years, and I’m realizing just how integral driving has been to us. I shouldn’t be surprised because in her family at least it all comes so naturally. She tells stories of how her father would drive her, her two sisters, and their mom from Iran to France and back. In fact, not long after her parents married, they made such a drive and bought an imported American car, a Pontiac Tempest, in France. Her mother didn’t know how to drive, but learned on the road from Paris to Tehran. My wife’s father passed away twenty-five years ago. Her mother, in her mid-eighties now, still wants to drive, though after a few accidents, we don’t think it’s such a good idea anymore. But I get the impulse, the independence driving conveys. I feel it as intensely as I do anything else.

In our years together my wife and I have driven far. Once we moved to our current home in upstate South Carolina, we both got jobs fifty-plus miles from our house, and twenty miles away from each other. So five days a week, we drove from 180-200 miles round trip, depending on who got dropped off first. It was more wearing on our car than us, because we were together on these trips, listening to Radio Reader on NPR or to mix tapes I made on weekend days. When my wife became pregnant, we’d have to leave even earlier to account for all the stops we had to make to let her get sick in McDonald’s restaurants or on the side of the road. She quit her job when the baby came, though the day before she went into labor, she drove us that entire distance, and when we got back to our town, we decided to go to a movie.

Driving Miss Daisy.

After our first daughter was born, we learned other late night driving routes. She often had ear infections that made sleeping difficult. So our doctor advised that along with the antibiotics, we should put her in the car and drive her around until she fell asleep. So the three of us would journey to the beaming red neon of Krispy Kreme, load up on sugar and caffeine and then venture into the wilds of Greer or Duncan, San Souci, and Woodruff. We’d put in the soundtrack to Twin Peaks, and something about Angelo Badalamenti’s lush tones and the rhythm of the road soothed our baby. When she was two, we made a cross-country trip and wore that tape out somewhere in Utah, a state where I was also stopped on a mountain road by a trooper. I was switching lanes without signaling, he said, something I like to do when I’m descending curvy mountain roads. He looked in our front seat and saw a rolled up brown paper bag.

“What’s in that?” he asked.

“Here, I’ll show you,” I said.

My wife likes to make a nut and raisin trail mix for our drives.

The officer laughed and let me off with a warning.

The rest of the trip was uneventful until we drove past Kansas City.

“Keep going,” my wife commanded. “I don’t like this place and whatever you do, don’t stop!”

I had never intended to stop in Kansas City anyway, but after that warning, well, I never plan to visit that town, and I don’t care what it offers.

We did stop, though, back in Wyoming, when we saw a sign advertising deep-fried cheeseburgers. I don’t know about you, but as a native southerner, the thought of someone deep-frying a cheeseburger for me is somewhat akin to offering me a free ticket to an Alabama-Auburn game. I’m 58 years old now, and cholesterol being what it is, I probably will never have another deep-fried cheeseburger. But I had one once, and it was among the five best things I’ve ever tasted. The other four? Fried oysters; my mother’s spaghetti and meatballs, recreated from our Italian neighbor’s recipe; seafood gumbo from the Bright Star in Bessemer; and a cup of café con leche somewhere west of Madrid as we were driving through the Spanish countryside.

*****

So, it might have dawned on you that many of our road trips are accompanied by or end with some sort of food. And it’s true. That may be the point of this story, or it may just be what happens along the way. But for me, the point is this:

My wife can’t cook, or rather, she can but doesn’t enjoy it. She likes multi-tasking, and I’ve learned through the years that the one way you shouldn’t cook is when you’re trying to do four or five other things. Once, my wife decided that while something she was cooking was in the oven, it was imperative that she run out to Home Depot. Which she did.

We ate out that night.

On our earlier road trips, she also liked to pack us sandwiches, fruit, and other goodies so that we wouldn’t have to get our food by chance. Maybe she didn’t enjoy that deep-fried cheeseburger as much as I did.

But lately I’ve noticed that she’s easier about our trips, what we pack and where we stop. Maybe that’s because both of our daughters are grown and she doesn’t have to worry about the lack of nutrition they might be getting at roadside inns. She also seems more willing now to let me lead us to places I know about or have read about. Is this an indulgence or a form of love?

Recently, we took a trip to Mississippi where I was the keynote luncheon speaker for a Faulkner heritage event. I know that when you tell some people you’re going on a vacation to Mississippi, they look at you like you want to force-feed them deep-fried cheeseburgers. But as she usually does, my wife looked on this trip as an adventure. After we got to Birmingham, we were able to take backroads the rest of the way. And on US 78 West, thirty miles outside of Birmingham in a town called Dora, my wife allowed me to lead us to one of “those places”: Leo and Susie’s Green Top Café specializing in pit-cooked barbecue. Pork. Now while my wife isn’t Moslem, she did grow up in a land that fears the pig. So she got the BBQ chicken while I indulged in the large pork plate. She did order a big plate of fried onion rings, so I’ve corrupted her that far at least.

When we first walked into Leo and Susie’s, though, it was one of those strange encounters with the locals. Everyone in the place stopped talking and turned to look at what had walked in the door. There are plenty of people who would have left at that point and found the nearest Zaxby’s. Not me, and more importantly, not the person with me who trusts me as much as I love her. For how many people would take this chance with me, follow me on this long road? In fact, in getting there I missed the turn because sometime in the last decade, the state thought it expedient to build a new four-lane highway that bypasses Dora and Sumiton and Jasper. Neither Mapquest, nor my Alabama barbecue guidebook thought to inform me of this new turn. So it was my wife who calmed me down when I realized my mistake. It was my wife who Googled the directions to Leo and Susie’s, and who successfully drove us there. She made photos of the place and sent them to our daughters, too.

As we left the cafe, driving in the early November dusk, I pointed out to her a turn which led to the house of a girl I dated back in college. For the short time I dated this girl, I’d have to drive the sixty mile round trip twice to get her, take her into Birmingham for dinner and a movie, and then back again to her home before returning to my parents’ home in Bessemer. When I told my wife all this and pointed to that road, though, she just smiled and said, “Uh-huh.”

I took her hand then as we drove. “You know, one of the things I love most about you is that you’re the kind of person who’ll get lost with me as we try to find a BBQ joint I’ve read about somewhere.”

“I know,” she said. “I always have.”

Once when I was especially anxious about some event—a doctor’s visit or an impending financial decision--she told me that in such moments I should search my mind for “that comfort place,” that place that makes me happy. Full disclosure: my wife is a psychotherapist.

I take her advice often. And when I do get anxious, the place I go to is that road, that piece of state highway near Dora, or the one beyond Lenoir City, or somewhere in Greer, or Wyoming, or even Pleasantburg Road by the Krispy Kreme.

In that place I’m never alone and I’m always comforted. Because she’s always there, just as she said she would be when we were standing in that maintenance shed all those years ago.

Terry Barr's essays have appeared or will soon appear in Red Fez, The Museum of Americana, Drunk in a Midnight Choir, The Rain, Part, and Disaster Society, and Belle Reve Literary Journal. Barr is a two-time Pushcart nominee and lives in Greenville, SC, with a wife and daughters.

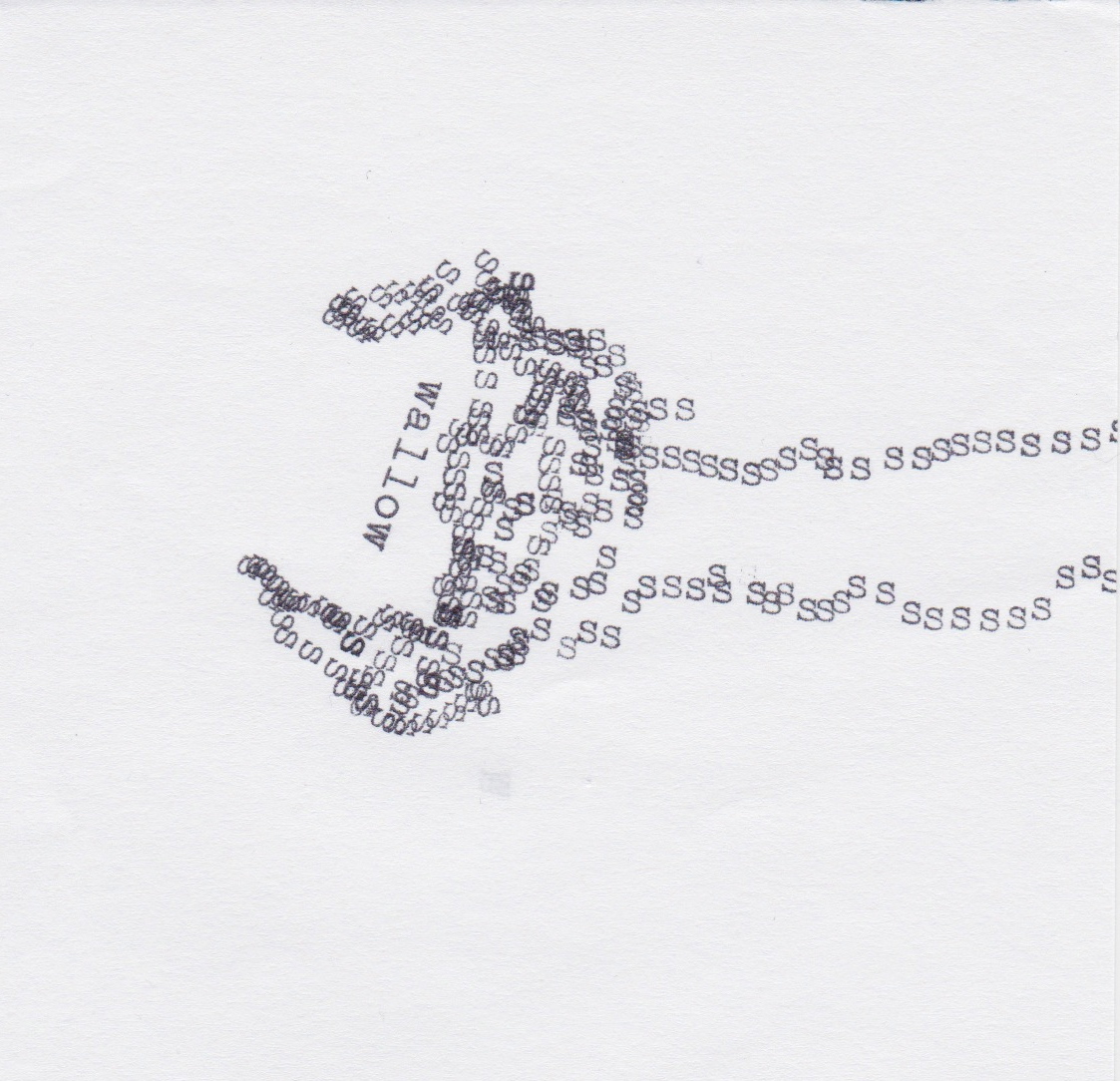

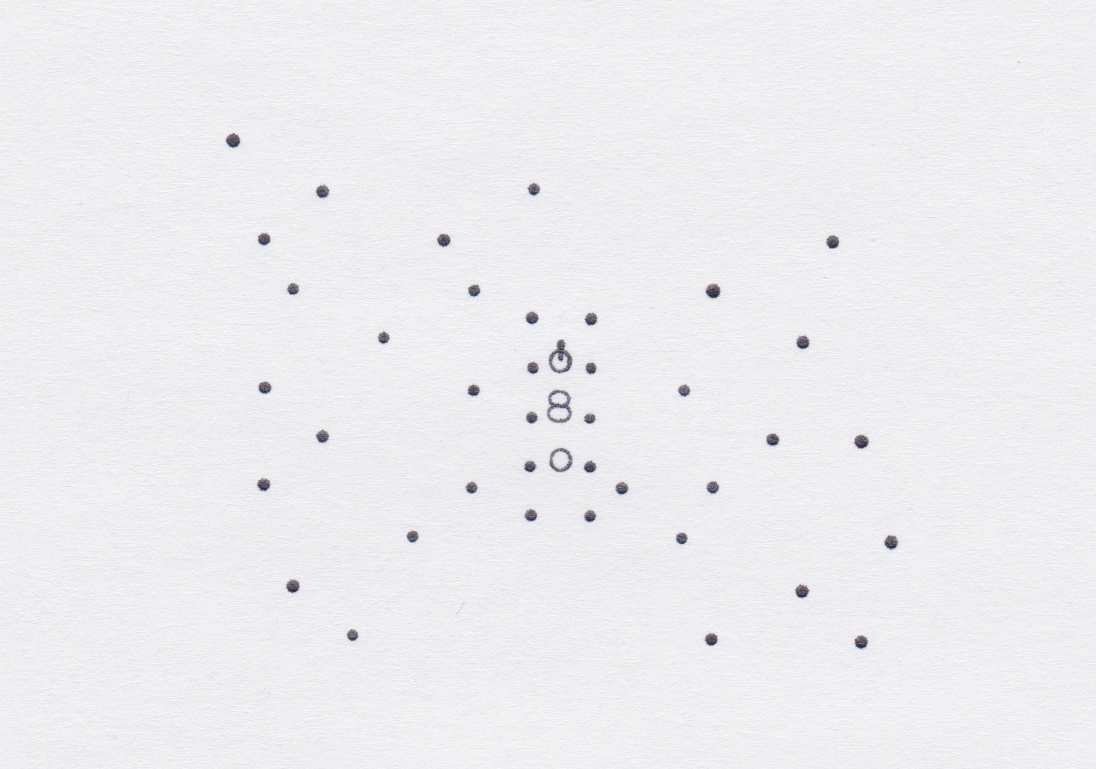

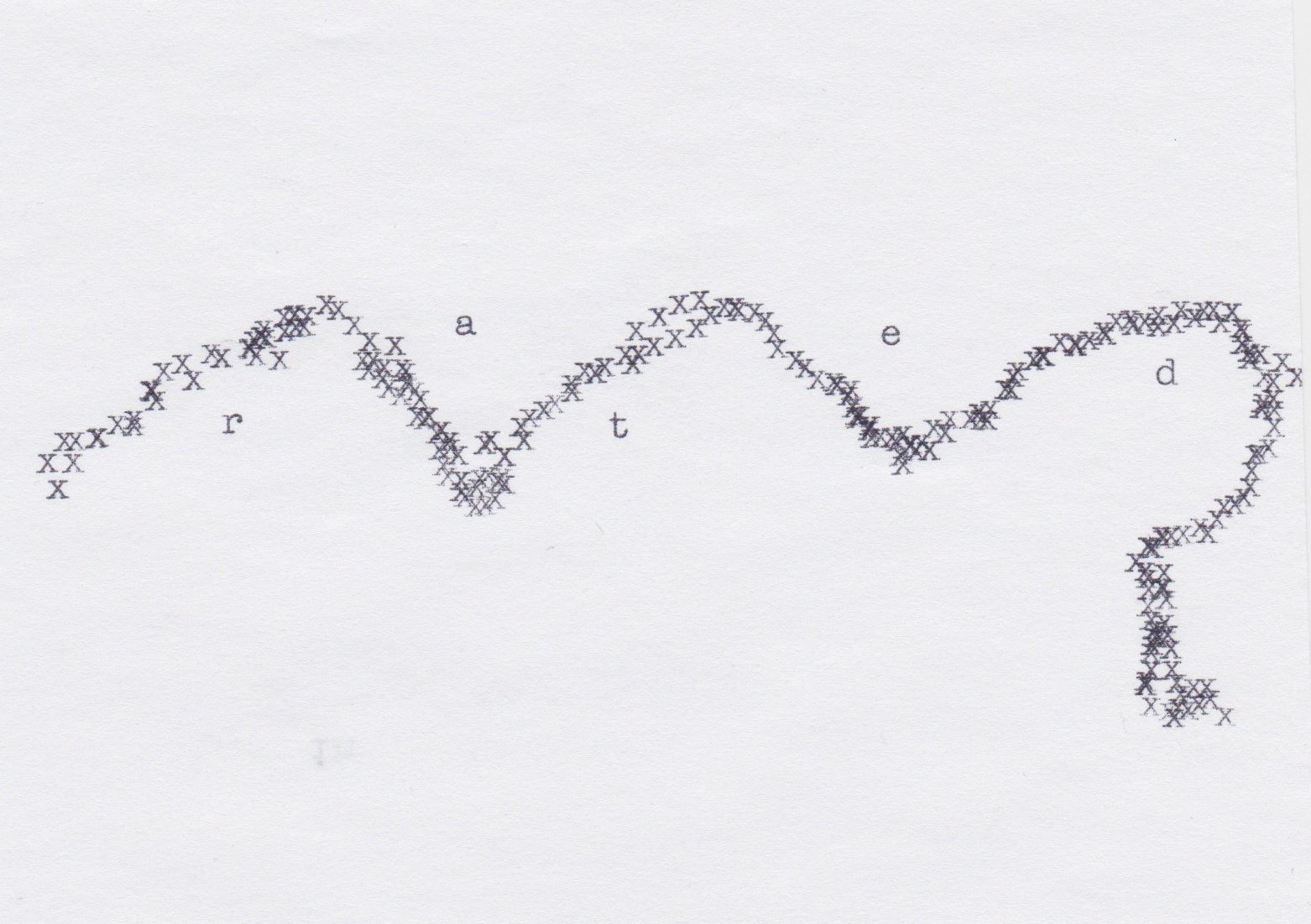

"horse to the left"

"swallow"

Michael Prihoda is a poet and artist, born in the Midwest. He is the founding editor of After the Pause, an experimental literary journal. He enjoys nature and the feeling of falling asleep. He tweets @michaelprihoda and blogs at michaelprihoda.wordpress.com.

Michael Prihoda is a poet and artist, born in the Midwest. He is the founding editor of After the Pause, an experimental literary journal. He enjoys nature and the feeling of falling asleep. He tweets @michaelprihoda and blogs at michaelprihoda.wordpress.com.

Fishing on a Wisconsin lake

and what I remember is the sunlight

on the pier, the rot of the boathouse

and how you could sit and wait,

and I never could, and neither of us

caught a thing.

Carving a pumpkin

and what I remember is the sweetness

of it, the feel of the knife

in the flesh, the shape

it took, the taste it offered

a tongue too eager.

Fishing in Georgian mountains

and what I remember is hard

earth, the sound of water

in its yearning for the sea, and

the smell of browning butter

and nothing like a fish.

Ordering pizza in Washington

and what I remember is a hotel

room on a cracked asphalt lot

you in uniform, lies pinned

to your chest, some you told yourself

some you told me.

Sharing a girl I brought home

and what I remember is how old

you seemed, and how young

we felt, and how you looked at her

like a starving child, with tears

in your eyes.

Swimming in a Florida pool

and what I remember isn't the pool

at all, it's the end

of that thing you made with my mother

that thing that made me

that thing you fled from

like everything else, like me.

Singing an opera while making spaghetti

and what I remember is the taste

of the meatballs, the sound

of our singing, off-key,

off-point, off-task, not

nearly of-ten

enough.

Standing by your bed

and what I remember is the sound

of the monitor and the intimacy

of its echo eleven years later

as I lay staring at a different

same ceiling, listening to a different

same sound, and living.

Standing by your bed, a breath later

and what I remember is the speed

of it, how everything slowed down,

how your wife looked away, and the roar

of rage that filled my head,

that still fills my head

the sound of you

and your going.

Peter BG Shoemaker writes nonfiction, fiction, and poetry from a mountainside in the desert Southwest. More at petershoemaker.com.

Michael Prihoda is a poet and artist, born in the Midwest. He is the founding editor of After the Pause, an experimental literary journal. He enjoys nature and the feeling of falling asleep. He tweets @michaelprihoda and blogs at michaelprihoda.wordpress.com.

A Lapsed Applause

An apprehensive comic.

A boondoggle to the entertainment sphere.

An emphatic crowd, a boon to this, the entertainment titan.

The first joke trickles from the stage and into the ears and amygdalas of those who’d spend $30+ on a Night Out at a Comedy Club to chuckle at the words

“Everyone fudges figures in the clerical sweets shop.”

The den’s light sustains its staid and nonjudgmental glow and before the crowd reacts the light continues to hue the place as a purpled center of cultural feed. Laughter resounds but backstaged, crossarmed contemporaries pile their remarks. How his hair so fits his dress. How his cadence mirrors Hicks. How the inept fillers who’ve infused the den with their staleness know nothing of the tough roads trekked to craft such auditory mood alternators. They smother and sully their closers. They nibble nails to quell the distant froths of expiration.

Compact pills of marginal relief go swallowed by a personage who’d drive thirteen blocks, circle three more for a Spot, and pay $33 to giggle at the words

“When I shop for new pants, I always trust Jean-Clad van Denim’s.”

In a review posted a week later to a Relevant Website, the material is praised for its honesty and visceral collar-grabbing velocity, and the words “erupt” and “laughter” are joined in tight proximity as a summation of the night’s tone.

Comic & Crowd journey home,

each to perform rites of differing intensities

in step with the sparked chords of a twisted carol.

Boredom & Bedroom sums the crowd, Replay & Refine, the comic.

In the still latitudes before sleep, both parties weigh the night’s value, their place in the coming closer, and snicker at the words

“We could cut pallbearer fees if we held deadlift competitions in the graveyard.”

Electric Eye

Adjusting the furnace’s electric eye I caught my thumb in its guard’s rusty hold. Observing the mess, I saw its squeeze had yanked my pad in reverse. Quickening with a stale mind and the wit of a dolt, I forced the effort and detached the turgid stub from its place on my hand.

Hearing my pain, the customer’s daughter entered. Acknowledging the pooled mash and my gunky shirt a surgical cheesecloth, she made a motion to aid. Mistaking the finger’s strength with a brawny boulder’s, she bent it swift and I hollered. Gasping the action, she retreated.

Pondering my state alone, I solved she would return with the others. Jogging from the land lot, I questioned if the customer would note what I made my own that day: three hundred paper towels and a lesson in cautionary motion.

Pal LaFountain lives life in threes. This explains the number of capital letters in his name.