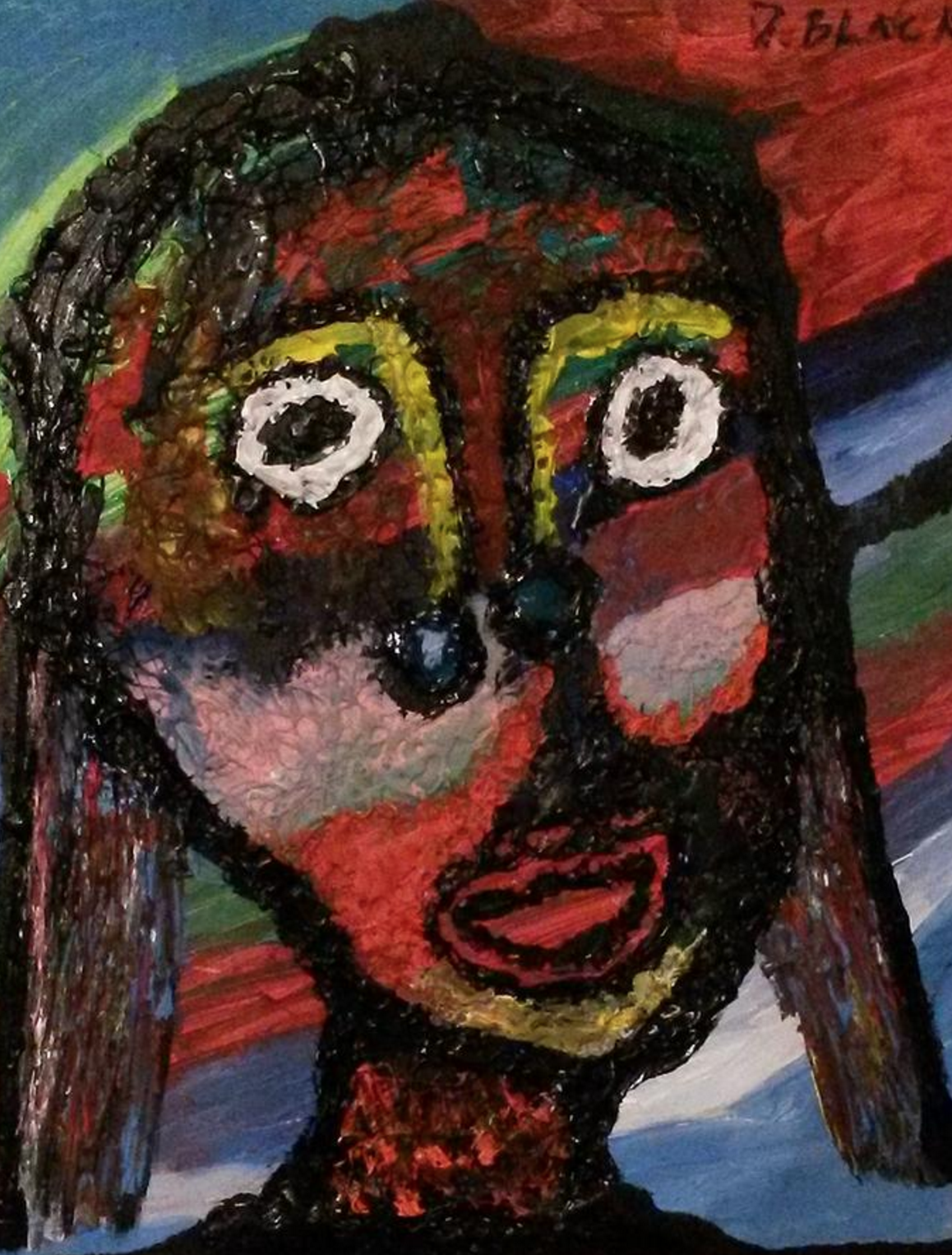

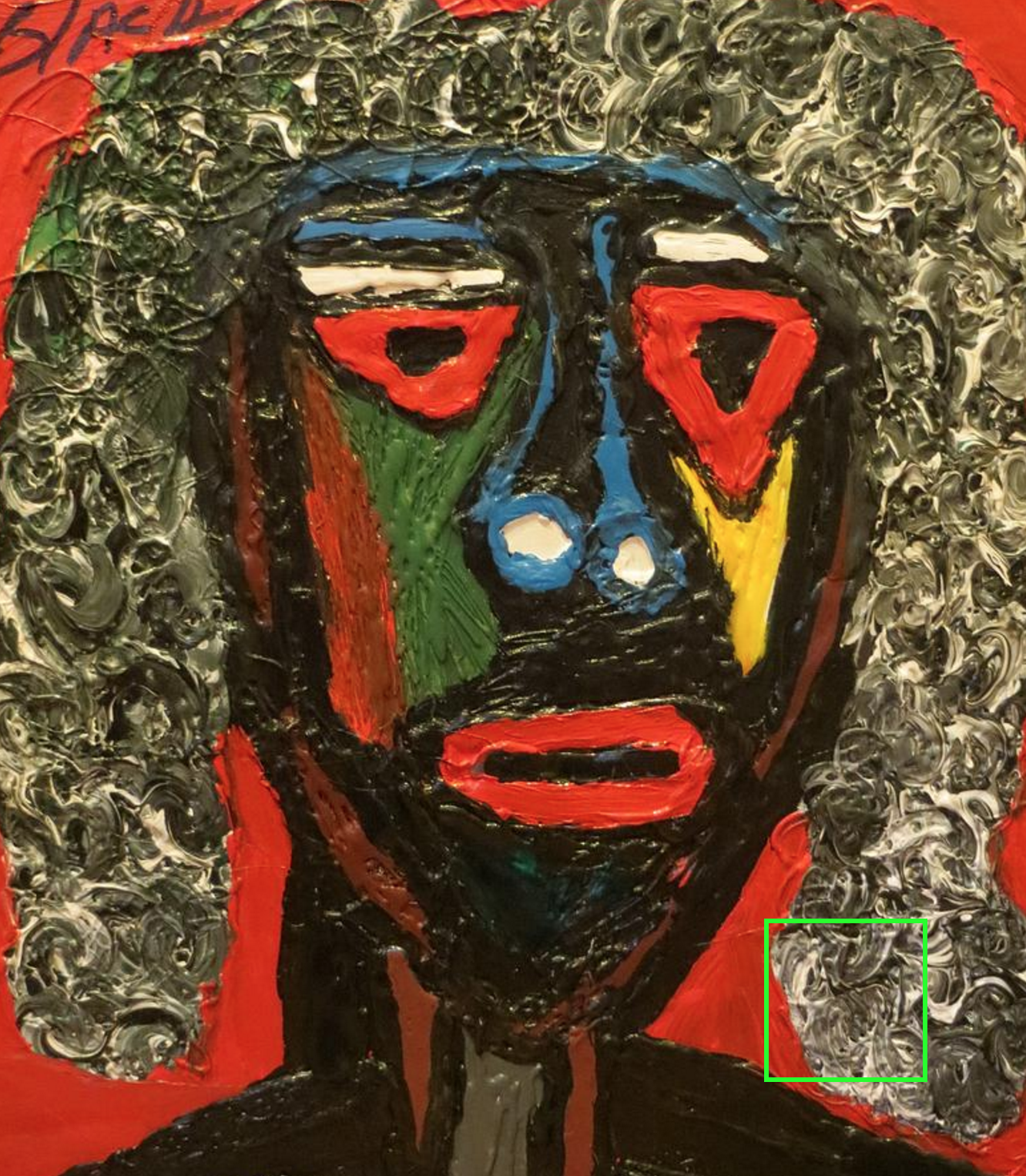

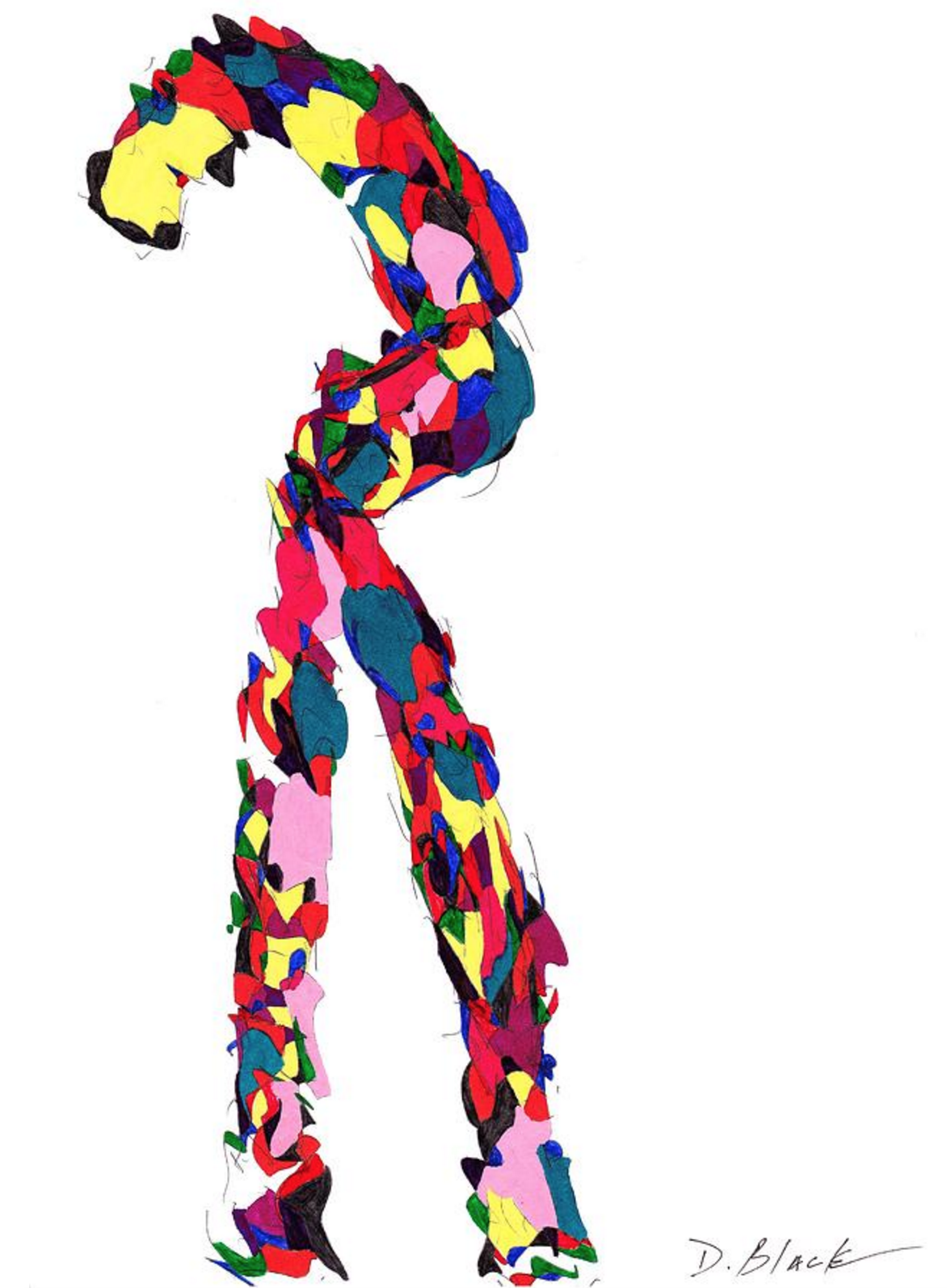

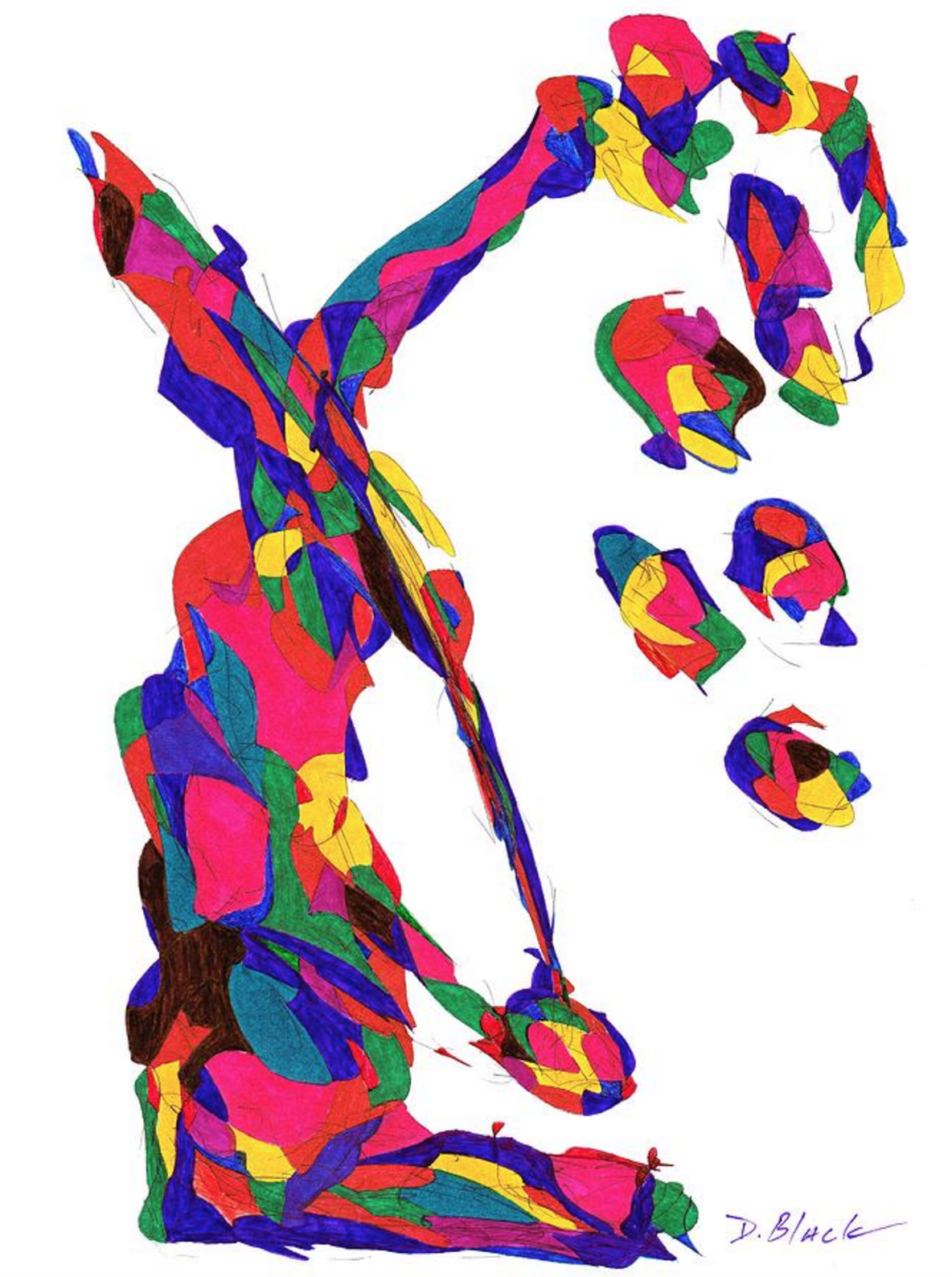

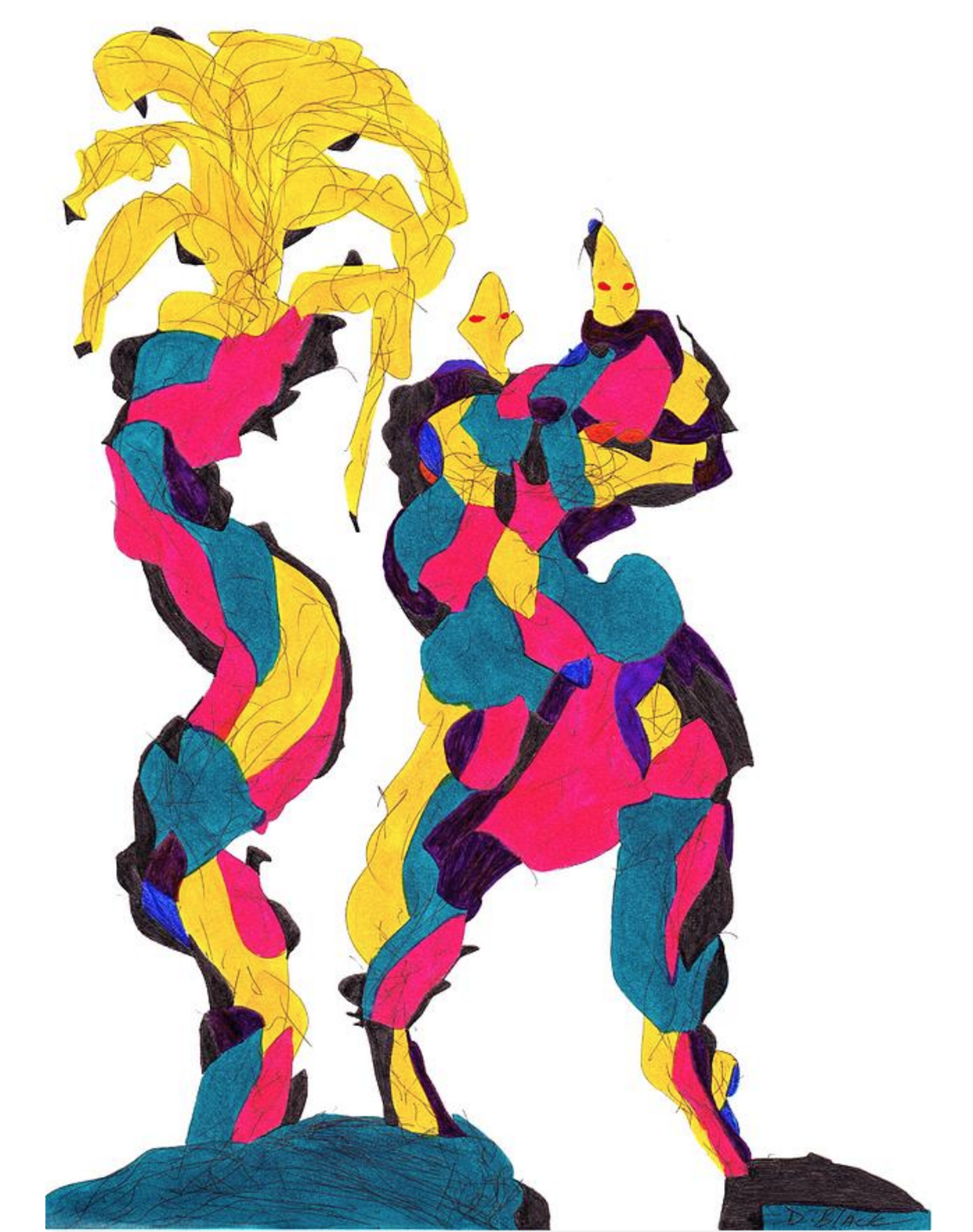

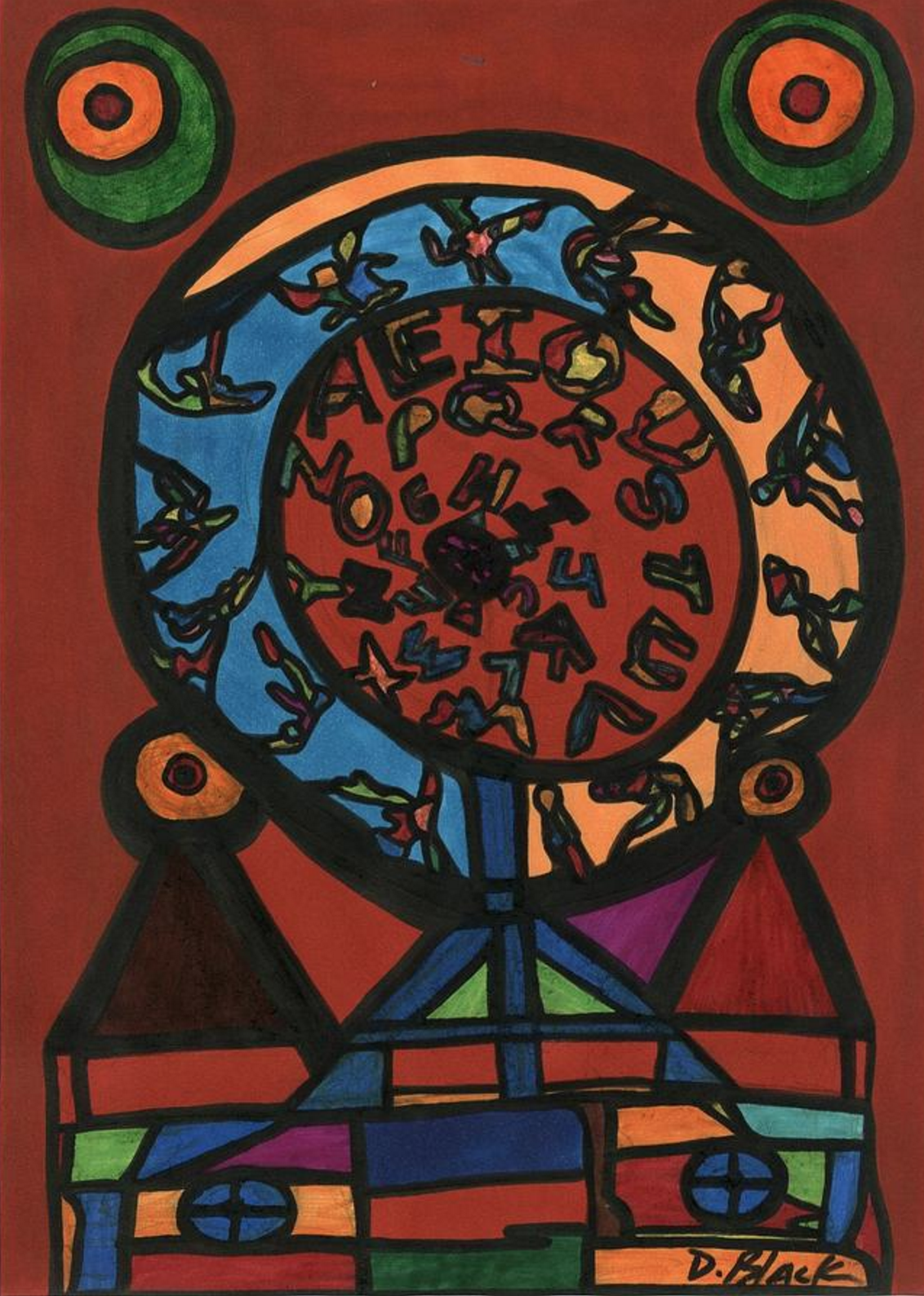

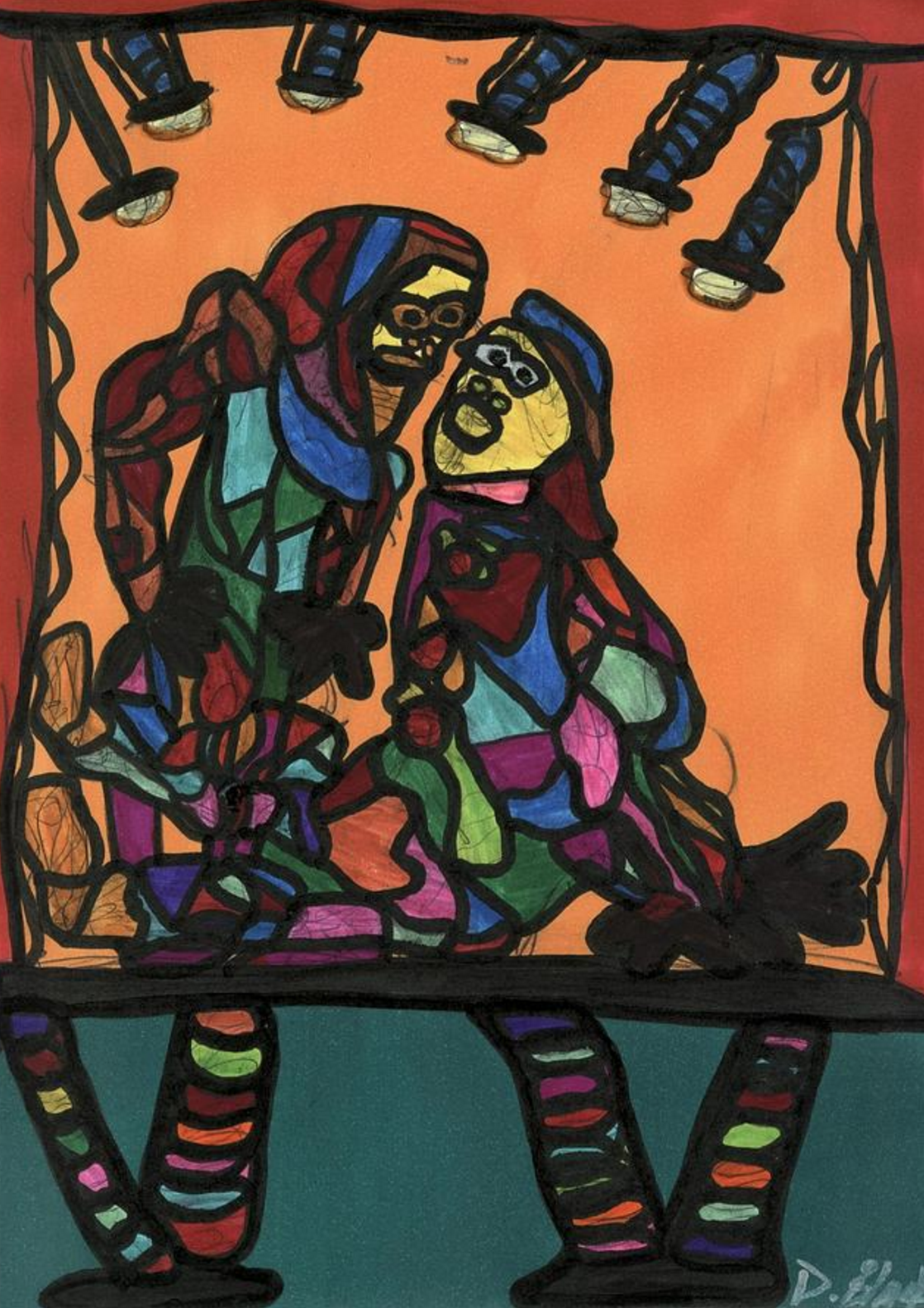

Darrell Urban Black is a visual artist living and working in Frankfurt, Germany. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, where his artistic pursuit started at five years old. He has participated in many local, national and international group art exhibitions, and has artwork permanently displayed in a number of art galleries, museums and other institutions in the U.S. and Germany.

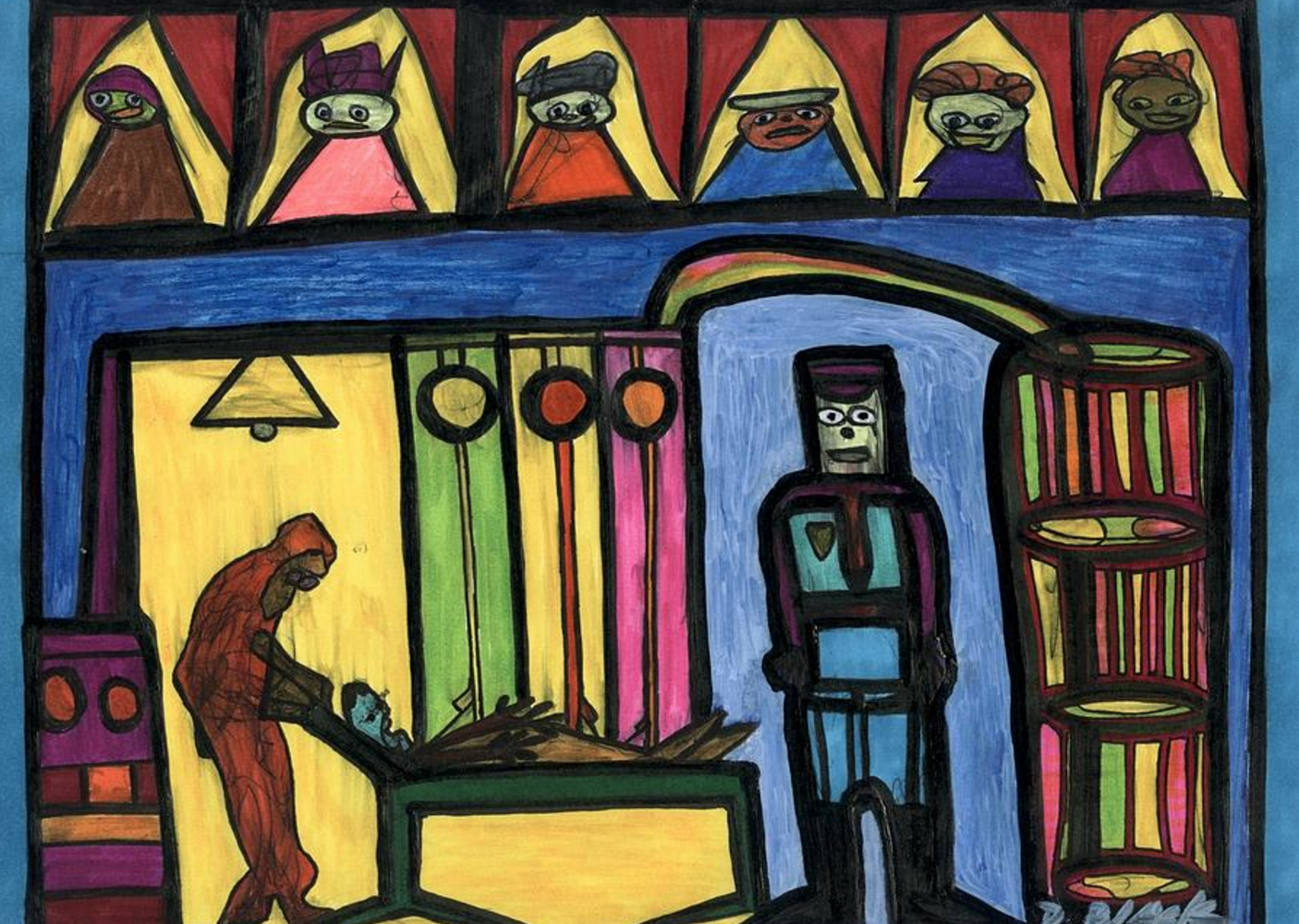

DAY FOUR: Selected Artwork /

Darrell Urban Black is a visual artist living and working in Frankfurt, Germany. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, where his artistic pursuit started at five years old. He has participated in many local, national and international group art exhibitions, and has artwork permanently displayed in a number of art galleries, museums and other institutions in the U.S. and Germany.

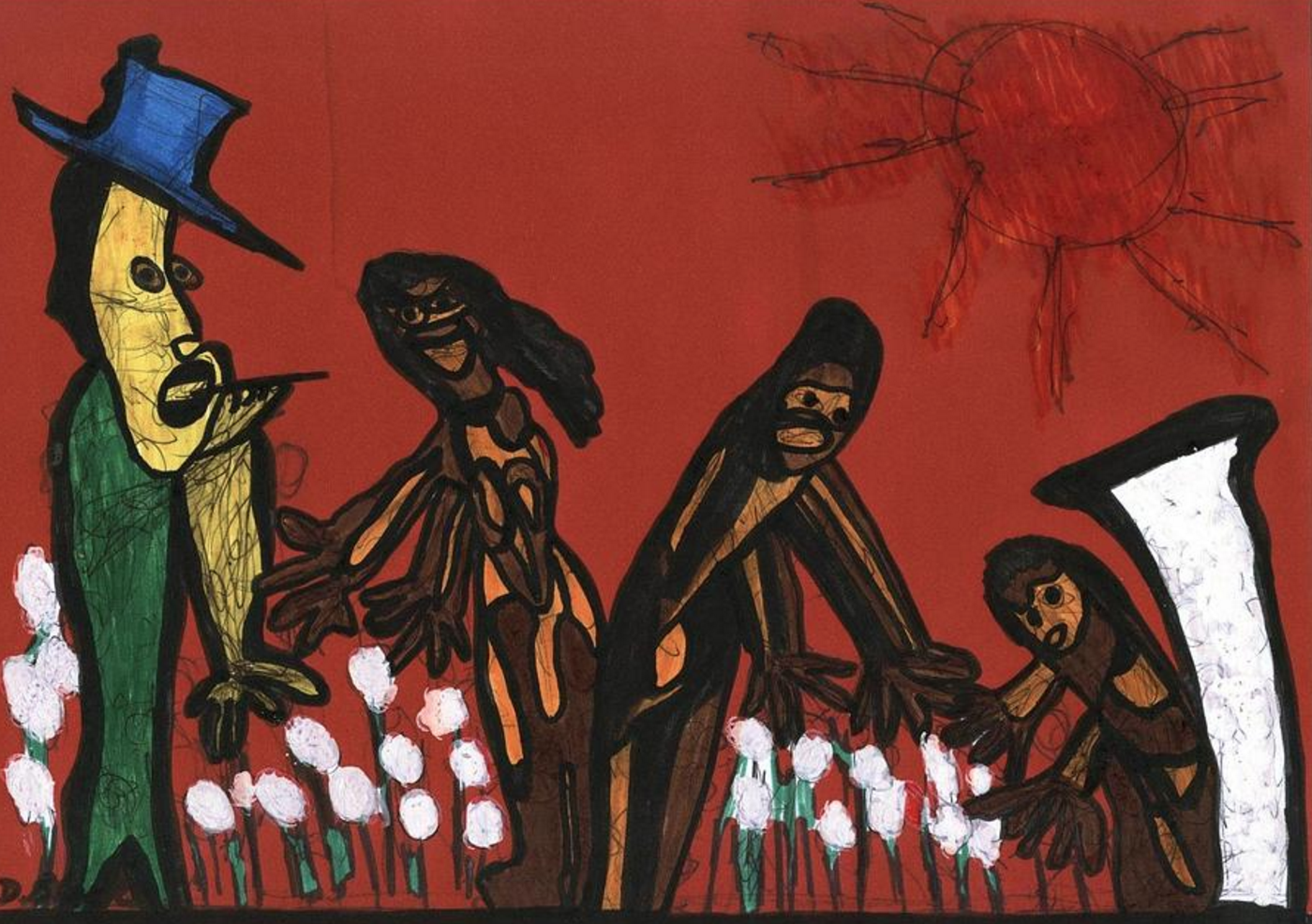

DAY THREE: Selected Artwork /

Darrell Urban Black is a visual artist living and working in Frankfurt, Germany. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, where his artistic pursuit started at five years old. He has participated in many local, national and international group art exhibitions, and has artwork permanently displayed in a number of art galleries, museums and other institutions in the U.S. and Germany.

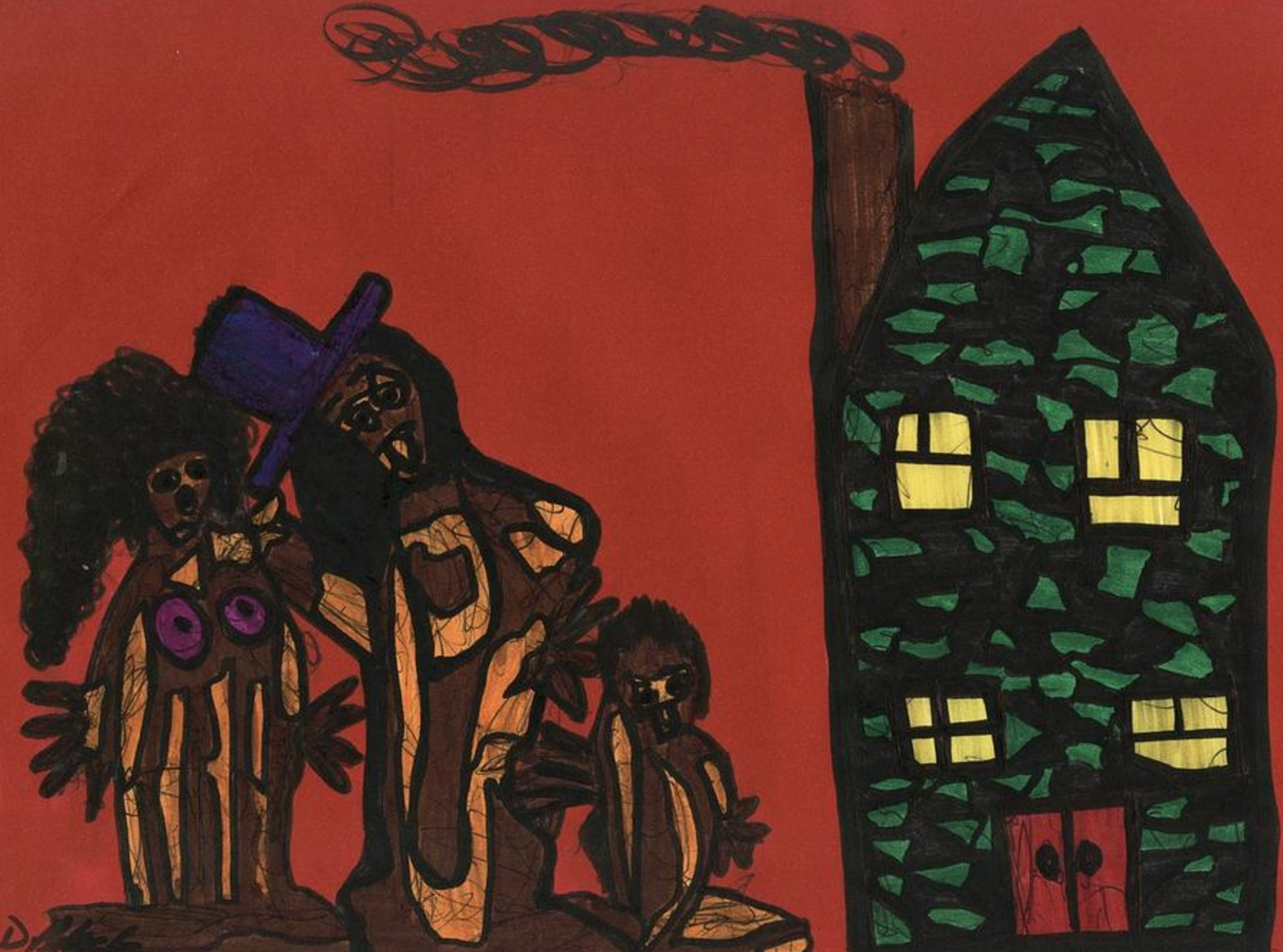

DAY TWO: Selected Artwork /

Darrell Urban Black is a visual artist living and working in Frankfurt, Germany. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, where his artistic pursuit started at five years old. He has participated in many local, national and international group art exhibitions, and has artwork permanently displayed in a number of art galleries, museums and other institutions in the U.S. and Germany.

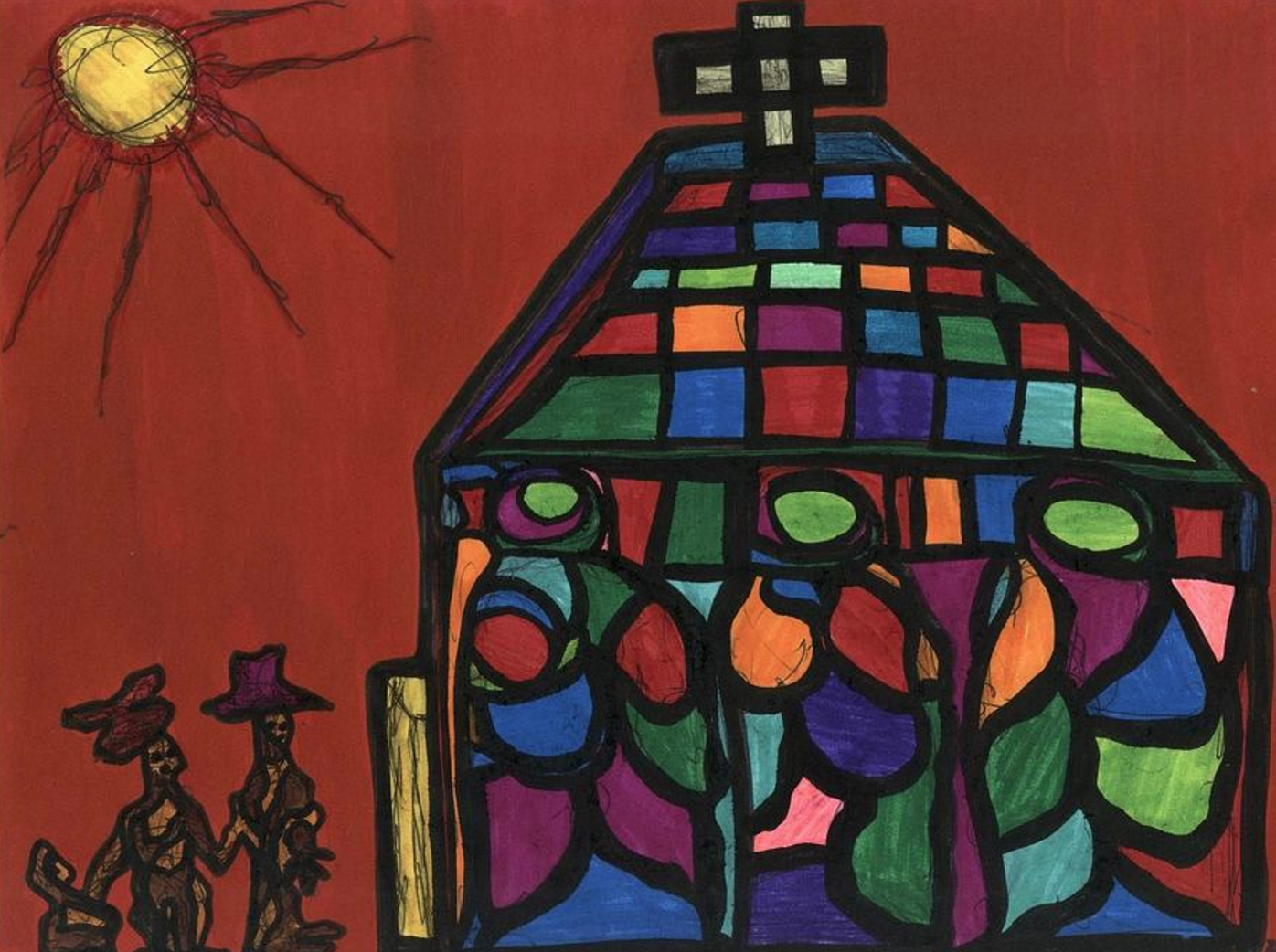

DAY ONE: Selected Artwork /

Darrell Urban Black is a visual artist living and working in Frankfurt, Germany. He was born in Brooklyn, New York, where his artistic pursuit started at five years old. He has participated in many local, national and international group art exhibitions, and has artwork permanently displayed in a number of art galleries, museums and other institutions in the U.S. and Germany.

The Red Bike /

His elbows on his knees, he stared down at the laces on his shoes. How long had he known the old man? He remembered he'd just celebrated his tenth birthday when his mom had ushered him into the store to meet Mr. Feldman, and a deal had been struck. The grocer needed a boy to sweep the store afternoons and Saturdays, and in return for his services, his mom could select slightly aged produce at reduced prices, still good, but not good enough for the daily trade. And, she was allowed to buy day-old bread at half price.

"He was a fair man," a bass voice echoed from the front of the chapel. Will watched his scuffed shoes swing under the pew as his lips silently repeated the phrase. He was a fair man. He could imagine a hand reaching down with a piece of penny candy, but never recalled an instance when this had actually occurred.

Will had been taught to make himself scarce when shoppers came into the store. He was to keep the floor free of dust and debris, dust the shelves, but never to be seen by the shoppers. Some days he'd have long waits behind the back room curtain watching transactions and exchanges of pleasantries at the counter. And when he heard the bell over the door, he'd peer out to see if the store was empty and, if so, he'd continue his daily tasks.

This routine had continued unchanged for a couple of years until one day he was called into the old grocer's small, cluttered office in the back of the store.

"Will, you are old enough now to deliver groceries to the back doors of our customers, those who are unable or unwilling to come into the store. How would that suit you?" he said.

"Fine, I mean, I'd like that Mr. Feldman."

"Now Will, because of our need to make multiple deliveries time to time, you will need a bicycle with a basket to carry groceries, and—"

"I don't have a bike," Will interrupted.

The old man paused and peered over his glasses at the boy.

"Well, do you suppose you could get one?"

Will felt perspiration dance across his neck, his hands searching his pockets for some unknown purchase.

"I…I don't know, sir, I could ask around."

The old man nodded and reached for a pencil that rested over his ear and used it to scratch the back of his neck. He smiled at Will's wide eyes and winked, "Where there's a will, there's a way."

The boy looked puzzled, but said nothing. He sensed that the meeting had ended and returned to his duties in the store. And he wondered what he would do now. He knew the cost of a bike was beyond him, even with his mom's help. And to his knowledge, none of his friends owned one. Everyone he knew walked to school.

Up front two men in black suits closed the casket. Everyone rose in silence as the dusky apparatus was wheeled down the aisle. Will squeezed his eyes shut just as he had when his mom insisted they go down front to view the body. He could hear the old man's words as if he'd spoken them yesterday! Where there's a will, there's a way.

Once they were home from the funeral his first order of business was to kick off his shoes. It was summertime, bare feet weather. Leather shoes always hurt a kid's feet. Now back in his overalls Will sat at the kitchen table eating lunch, graham crackers and milk. It would be the same each day until school started in the fall. Then his mom would place a peanut butter and jelly sandwich in his school lunch sack. And this suited him. PBJs were standard fare for all kids.

The bike was on his mind. He and his mom had canvassed the neighborhood for days looking for someone who owned a bike and would loan it to him. But no one had a bike. Even the adults, for the most part, depended on bus service for daily commutes. All appeared hopeless to him until Mr. Feldman proposed a solution. He would furnish a bicycle to the boy and Will would pay him a quarter out of his new dollar a week wages until the debt was settled. And before the old man presented the bike to Will, he'd had it painted bright red.

Will soon became the talk of the neighborhood. Everyone wanted a ride, and he would quickly oblige anyone who could scrounge up two cents for a trip to the end of the block and back.

Will knew he still owed money on the bike, but to whom? The old grocer had been a widower and had no children as far as anyone knew. He finished his milk and shambled out onto the front porch to inspect his treasure. It stood gleaming in the light, safely secured by a chain to the banister. Too easy for someone to steal it otherwise. Nothing of value would survive a night outside in this area of town unless it was protected in some way. He bent down to take a closer look at the tires. There was plenty of tread left, but he could see small cracks in the rubber. It wasn't a new bike, but new to him and a good bike, too, he thought.

His mom came out of the house and passed him in a blur, shouting instructions. She had a job as a dispatcher for a commercial truck terminal from noon until midnight and today she was late because of the funeral.

"Will, remember to sweep the front porch and empty the kitchen trash before I get home. And don't stray too far from the house. You know what we talked about earlier."

Will recalled the lecture about the gangs in the area and how they recruited kids to become drug mules. The money would be good, she'd said, but the end result would be a prison term or a violent death. She'd preached this so often Will could almost recite the speech himself. And he could hear her continue to rattle off tasks for him to do as she scooted up to the street toward town.

His summer afternoons had been filled with grocery deliveries, but no more. He rode his bike up to the store and peered in the dark windows. Who would buy it now, he wondered? And would the new owner hire him? And would his mom have the same deal with the new grocer? So many unanswered questions.

The late sun bore down and he could see no one out to play. He chained the bike to the porch, flopped down on the sofa and flipped on the television set. Soaps, melodramas. He didn't know those terms, but what he did know was that every episode was filled with adults, sometimes in bed, engaged in endless conversations that made no sense to him. He'd no clue what the attractions of these programs might be, but when the subject arose at home, he recalled his mom had mentioned the woman across the street. Every evening he'd see a stream of men come and go, and Will had been told to stay away from her house and not to speak to the men who visited the woman.

The afternoon heat warmed the house and Will soon fell asleep. His dreams were filled with rides through the streets and across the park on his bright red bike. And days when he'd wave to other children on his way to important deliveries.

He awoke with a start when he heard noises toward the street, and raced to the door. Outside in the dark he could see links of the chain curled on the porch in the early moonlight. He ran to the curb and looked up and down the empty street, then hurried to the nearby corner, his heart thumping. But the only movement he saw was a dog with his head buried in an overturned trash bin down a nearby alley.

His head down and shoulders slumped, Will made his way back toward home when an old pickup truck, its innards rattling, pulled up next to him and stopped.

"Will, that you?"

"Yes sir, Mr. Simmons," he said. Moses Simmons was a neighbor who painted houses dawn to dusk, seven days a week.

"You don't look too good, boy. What's up?"

"Somebody stole my bike," he chuffed.

"You see who did it, Will?"

"No sir, I was asleep."

"Well, get in and let's circle the block. Maybe we'll see it."

For almost an hour the rusty old truck cruised the neighborhood, sometimes stopping so Moses Simmons could speak to folks cooling themselves on their stoops. No one had seen a red bike. And no one knew who might do such a thing.

In the wee hours of the morning when Will's mom returned home, he was asleep in front of the television set, its wide eye broadcasting a cloud of light and a hum. She gazed down at her son's innocent face and covered him with a sheet.

At first light Will was out on the streets searching every yard and alley and stopping everyone he saw. And it occurred to him that the one place he'd failed to search was the town cemetery. But why would anyone leave a bicycle there? He'd no idea, but he felt a need to look anyway.

From one end to the other he searched but saw nothing but gravestones, markers, and various monuments. New remembrances lay strewn here and there, some fresh, some plastic. And some graves were adorned with nothing more than weeds and crabgrass. And then something caught his eye: a fresh mound of dirt, a new grave. Mr. Feldman. It was still too soon for any markers to be placed here, but he was sure this hillet represented the final resting place of his former employer and friend. He could see the old man's wrinkled smile. Do I still owe you? You don't happen to know where my bike is? In the stillness, the only sound he could hear were two wrens fighting over a tidbit below a tree nearby shading the new grave.

Over the summer Will's discouragement festered into anger. He'd get even. Somehow he would. Every evening he'd sit on the porch steps watching people pass, wondering who in the neighborhood had betrayed him.

Late one evening in front of the television set an idea came to him. He was watching the Friday Night Fights. He'd become a boxer, an amateur and then a pro. He'd show them.

Unknown to his mom, on Saturday morning he showed up at a gym where local boxers trained. He begged Nick, the owner, for a chance to train. But that would cost money, he was told.

Recalling the words of the old grocer, Will agreed to dispense towels and sweep floors afternoons and weekends in exchange for an opportunity to learn to box. He was determined. And Nick was pleased with his work. He described the youngster as thorough and energetic, tenacious even. He did not need to be told twice to do something.

Winter afternoons and weekends found Will in the gym. And the memory of the red bike began to fade. Sometimes he'd think of places he'd not searched, and fellow classmates who did not like him. But he never looked for it again. And in some ways he secretly hoped it'd never turn up. His demeanor had coalesced into a burning determination to win in the ring. The fight game had become his passion.

When Nick paired Will with a fighter for training that first Saturday, he'd picked an older boxer, a seasoned veteran who'd seen better days. Nick watched them spar. Will was quick and caught on fast. The next Saturday Nick selected a younger boxer to work with Will. The results were the same. The boy was good. And each blow he took produced an equal or harder punch in return. A few weeks of this, and Nick decided he'd handle Will's training himself.

"Will, you have to expect to win…at all costs," Nick said, "and you can never leave your guard down. You got that?"

Will nodded as he danced and weaved, waiting for his new trainer to throw a punch. When it came, it glanced off the side of Will's head. And then another, and another until the young fighter began to tire. He'd been dazed by a couple of punches, but he never fell to the mat. At the end of his first lesson, Nick asked him if he had any questions.

"What if he's bigger than me? What do I do?" Will said.

Nick stared at him in disbelief.

"Will, do you want to win?"

"Yes, sir."

"Do you expect to win?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then why the question?"

The lesson was over. The trainer turned his back on the boy and walked off. Will knew what the expected answer would be, but he wanted the real answer.

Nick continued to add strategies to the young boxer's repertoire, and he told him,

"Will, a good idea has power, is power, and, if nurtured in a cauldron of angst and energy, it becomes an unstoppable force." Will's moves soon became psychic. An opponent would feint left and bob right into a gloved fist that would meet his head like a freight train at full speed. For some unlucky opponents, one solid punch was all it took.

Over time Will grew in breadth, height, and zeal. And he won. Time and again. Nick continued to match him with faster, larger and more powerful boxers. And like a Rembrandt, a Michelangelo, or a Botticelli, he'd become a master of his art: the art of movement, poise, and stamina. And raw determination. And a time came when few youthful fighters wished to face him in the ring.

At first his mom had been reluctant to allow him to fight. "Will, you could get hurt. Your face could be scarred for life, baby."

"Momma, it's me. It's my future. It's what I want to do."

In time she became his most ardent supporter. And he won the youth division title with no losses. By the time of his eighteenth birthday, the opportunity Nick had whispered in his ear so often was at hand: tryouts for the US Olympic Team.

Later his defeated opponents in this grand tournament would talk about their initial encounter with the young boxer. There was something mystical about his gaze. Every hopeful amateur knew there would be a faceoff and a moment when each would attempt to intimidate the other. A fighter was prepped for this moment, but with one look into Will's eyes, they knew. And he knew.

And perspective mattered. No amount of ingenuity on the part of the opponent could stop him. In Will's case, he'd embraced a discrete goal: every breath, every flinch, and every move was designed to be part of a singular force of destruction he'd unleash on his enemy.

By the time Will faced his first opponent in the Olympic trials, memories of the treasured red bike had waned, and the reasons for his competitive edge were no longer within his conscious processes. While he awaited the announcer, a thought flashed through Will's mind. Why am I here? As the din rose, his muscles tightened, and he peered across the ring at his opponent, a young sandy haired fighter from an Eastern bloc nation who stared back at him. What Will saw was a broad shouldered, tall youth who exuded total confidence. And for the first time in his boxing career, Will hesitated. Something was missing, but he couldn't say what.

The bell rang and the two Olympic hopefuls moved to the center of the ring, bobbing and weaving. And his body responded with the rote moves he'd practiced so many times with Nick. He thought he heard a voice and he blinked. In the next moment he felt himself falling. Everything moved as if part of an angry sea. Imaginary gnats danced across his eyes, and he remembered what Nick had told him if he took a fall. Stay put on the mat and breathe deeply until the referee says "six." Then rise and continue the fight. But Will had never been knocked to the mat. This was all new to him. And he wondered again why he was even there.

He shook his head and breathed. His vision cleared and he realized his opponent was nearby bouncing in bright red trunks. And in a flash the obsession that had driven him through all the steps that had brought him to this moment returned, and he heard the voice of the old grocer once again. He peered out into the animated crowd and thought he could see him shouting at him. The din was too great for him to have heard anyone, but he knew what Mr. Feldman would have been telling him.

He sprang to his feet at the count of eight, his arms and legs limber, his belly full of fire, and his energy bursting from his chest. The blow had changed him. It was a new game, a new quest.

Will danced backward and shook his head as if to clear it. His eyes narrowed, but his opponent didn't seem to notice. He shook his head again, and the sandy haired giant threw a wild punch just as Will connected with a bomb. The big man's legs buckled and he fell to the mat. Will's resolve then crystallized once and for all. No one would ever take anything from him again, nothing he'd ever worked so hard to earn. Nothing. Ever.

Fred Miller is a California writer. Over thirty of his stories have appeared in various publications around the world. Some of these stories appear in his current blog.

Voyeurs at Asnières /

John D. Ersing is a copywriter, journalist, essayist and poet. He lives in Brooklyn and just wants to remind you that Shonda Rhimes wrote the movie Crossroads starring Britney Spears. Find him on Twitter @jersing.

too small town /

I can’t stand people in this small town. They’re so content with the hand they’ve been dealt rather than ask for a re-shuffle. Some new cards, a new hand to help carry them out of the monotony of complaining about their mindless job or getting high in public or getting so drunk they can’t remember my face that used to loom down synthetically lit hallways lined with the evergreen metal lockers hardly anyone used.

Even meeting people from the small town over proves more exciting than going to the same bar and trying to carry out a conversation with someone who doesn’t care for their own life, much less mine.

The initial interest fades when I learn they, too, are sitting on a hand they’ve had for over twenty years with no signs of movement. Tricked by the new information only to learn I’ve heard the story been told, just from a mouth that dripped with liquor from age fourteen and is just as acerbic.

Because I’ve outgrown this way of living, have always strived to do more, be better, discover new things, I can’t simply sit on the same barstool and listen to the repetitive drivel. There’s not much else to do. So here I sit, resisting the urge to scream, imbibe, cry, and smoke, as the hours drip slowly from the etap and hit the bottom of the glass, hissing sarcastically and with an air of self-important knowledge only a fool could muster.

***

Julia Berke is a New York City ex-pat living on Long Island. She's a Library Assistant who doesn't shush students but still instills fear and is a frequent instagrammer (@joliajerky). She has collected all but two Neko Atsume special cats and maybe, hopefully, someday, will be pursuing a Master's Degree in Secondary English Education at [Insert School Name Here].

Selected Artwork /

Hong Kong bred, Sydney based. Henry’s artworks are personal, intentional, with a focus on storytelling. He always strives to assemble a full body of work, gathers scattered life stories, memories to form a collection piece by piece. With each individual art collection, usually consist of multiple pieces, often in the same style, grouped by specific themes, concepts or stories. By utilizing digital tools, a variety of styles can be seen across collections matching their subject matters. To view more of Henry's work, visit henryhhu.com

I Don’t Know What To Do With My Apologies /

Almost a week after Yom Kippur, I think about my relationship with the holiday, with my sins, with my guilt, and wonder if atonement is enough.

—

I started fasting on Yom Kippur when I turned 13, shortly after my Bar Mitzvah, and stopped my first year of college. It had gotten to a point where the ritual, although beautiful in some respects—as a cleanse, as a meditation, as an opportunity to get to know the parts of the body we rarely pay much attention to—often felt more like self-flagellation. The image of Paul Bettany in the Da Vinci Code film— skin painted white, eyes heavy and blood red, kneeling in a sparse room inflicting lash after lash upon his back…Yom Kippur became this. It became guilt, a punishment, and an occasion to offer up what felt to me like disingenuous remorse for sins past—sins that would be made tomorrow, early in the morning, before the coffee cools.

—

It had been a series of difficult mornings, and although I was grateful that the nights were easier after a challenging summer, getting up still proved to be a task. Even with the weather beginning to change, I’d wake up in a pool of sweat, possessed by a kind of anxiety that felt unfair to have before I was fully conscious of myself or any conception of anxiety. I often think this is the difference between those who have a disordered relationship with anxiety and those who do not. It’s a real problem when it’s in you all the time.

Taking the advice of a specialist who was convinced that the sooner I could cut off the anxiety the easier the rest of my day would be, I created a ritual that began with convincing myself of ten things I had to look forward to in the day. Anything from lunch with a friend, a bath I would take later that evening, the black sweater I’d wear to class. Mundane things made spectacular. Then I would breathe, making sure my exhales were twice as long as my inhales. I would do this until I felt good enough to get up, walk to the bathroom, and look in the mirror. This was part of it too. I had to see myself to ground myself. I had to say, “You are actually not a collection of dangerous thoughts but a full being with a physical form. Your feet are touching the floor. Your scruff looks good today.” When I would laugh or smile, I had to see myself laughing or smiling.

Yom Kippur morning was a particularly upsetting one. It had nothing to do with the holiday itself but the dream I had that night. It was a sex dream with someone I should not have been having sex dreams about. He called my teeth a work of art and asked if he could chisel the edges to make them completely even. He was naked and holding a blade. Dreams have a way of marking a day, and I woke up on the holiest day in the Jewish calendar feeling ridiculously horny.

I generally find my libido to be mostly unextraordinary, and as a result of this I am inclined to mistrust the few times where I have an intense desire for sex. The things I feel to extremes are not necessarily about that thing but often a product of another desire.

—

My sophomore year of college I was rejected by this guy I had feelings for; a guy who perhaps inadvertently, perhaps with intent, had me feeling like my sexual inexperience was a roadblock, a factor that made a romantic relationship between us improbable. I see this as tremendously stupid now. But at the time, it was the kind of devastating that made me go up to my then roommate and say, “Hey, I feel like shit. We should do something reckless tonight.”

So we did. We drank a lot, more than we usually drink. We snorted some things, even though neither of us had ever snorted things. At around 5 AM I opened up a sex app, which I had on my phone only because I had recently fallen into a routine of messaging strangers, letting them flatter me about something or other. Then I would block them when they asked if I wanted to come over or get a drink or smoke pot or—most crudely but often most respectably—if I was horny and just wanted to fuck. It was safe, undoubtedly annoying to the block-ees, but pretty inoffensive.

That early morning I did not want to fuck, was probably incapable of fucking, but found a guy who disarmed me with photos of him with his dog, a cute mutt. The man was about ten years older than me, lived just a few blocks away, and was chatting with me in a way that seemed innocuous enough. I am not the kind of person who enjoys sex without any form of established intimacy or communication. Yet suddenly, I was consumed by this intense yearning. It now feels incredibly misguided in a way so linear, so obvious, that I feel embarrassed at how oblivious I was to it all: I was rejected for my innocence and now wanted to be everything but.

He opened the door and—aftershave. That was all I could think about. It is all I remember. Not a name, not even a clear face. He was balding; holding two beers, but all I could think about was how overwhelming his aftershave was. There was also no fucking dog. I refused the beer, not wanting to risk losing grasp of the illusion of sobriety I had masterfully set up for this stranger, and walked into his tiny East Village studio.

We went straight for the bed, and by that point I already knew I didn’t want to be there, that nothing about the experience I was about to have would be exciting or satisfying or liberating. So I shut down. I became this sort of automaton, performing everything to the best of my ability but with no feeling or investment. He kissed and I kissed back. He went down on me and I did the same. It was not great, but I figured it was a rite of passage to have bad sex, to have sex with someone you shouldn’t have had sex with. It was something I could forget about. There was also a mild pride in my ability to do this, to detach when everything about me usually screams “here to stay forever.” I could have casual sex, hate it, and move on.

After a while of messing around, he suddenly held my wrists back and looked at me with an intense desire that piqued my interest if only because it was a divergence from how passive things had been going. Despite my repulsion of this dude and his aftershave and his ghost dog, it was nice to be looked at hungrily.

“I’m going to fuck you, little boy,” he said. I knew of the game, had seen enough porn to know of the power dynamic he was trying to set up, but I was not interested, had not agreed to any of it. I told him no, laughing it off, but he started rubbing himself against me, believing that I was onboard with his teasing. “Come on, little boy. Open up.” I repeated no several times then, and he didn’t budge for what felt like more time than had probably passed. He then released me, unconcerned, and we resumed doing what we had been doing. Ultimately he finished, I feigned too drunk to finish, and I left. I left with him asking for my number, in which I provided him with a fake, and shivering after he swore that we’d have plenty of other good times together. The last thing he said to me came out as a promise. He was going to fuck me, soon.

It took me a few months to think about that night, in full, to realize the incredible beauty of the nervous system and how it responds to threats—perceived and real. I may have been powerless for no more than ten seconds but it was enough to feel a pit in my stomach, for alarms to go off. A microsecond of not feeling in control, of feeling like someone could make you into something else, could destroy you, is enough. I felt ashamed and guilty and stupid.

—

I had just finished showering when I received a text message from a former co-worker, also several years older than me. He was in town for the week from Los Angeles and wanted to grab a coffee, but I knew he wanted more than caffeine and conversation. We had this back and forth thing, for a while, heavy flirting birthed out of the unethical. He was older, technically my superior, and for a while we played out these roles, entirely online—the boss and his younger employee. But he wanted to meet, today, on Yom Kippur. After catching up, he wanted to go to a nearby luxury hotel that had large, public bathrooms where we could mess around.

I knew I did not want to do this but I also knew I wanted to replace one set of preoccupations with another. The teeth. The chisel. A fantasy about my parents and his parents grabbing dinner, getting along, my mother whispering into my ear. “I’ve never seen you as happy.”

—

There was one year, when I was still in high school, where I woke up just a little dizzy on Yom Kippur day and convinced my parents that I was too weak to go to morning services. I still wanted to fast, but I wanted to stay in bed, rest; connect with God from the comforts of my bedroom. They budged and after they had left, I got up, took a long hot shower, and got right back into bed wearing nothing but a towel around my waist. I was just going to watch TV and read a little bit, but the solitude reminded me of a morning when I was four or five, a faint moment that lingers in part because it remains one my purest and holiest memories.

I am up early. My parents, still married, although maybe not happily, are asleep. I walk to our playroom, aware that our wooden floors creak, that I must walk on my toes. I do not want to wake my parents. I walk past our kitchen. In this memory, our house is filled with so much natural light. I don’t remember the house exactly, but it feels right to fill this scene with light, sharp lines penetrating our windows, revealing dust particles floating over the floors. I sit on our playroom floor, take out some toys, and begin to play. It is quiet but pleasant. Suddenly I hear a deep male voice, a baritone, whisper my name. I look around for my father but he’s still asleep. I instinctively know the voice came from outside and look out to our backyard, to the inflatable kiddie pool, the flowers my dad planted. It came from them, I’m sure. It came from the flowers, the ones with little green buds that, when you squeeze them, turn inside out, releasing a clear liquid and seeds.

I thought about this for a while, how sacred it all felt. And although at 16 or 17, Yom Kippur had been in a phase of my life that was about questioning and rejecting everything I had been taught, this was real and special and as warm as anything.

—

We met at a nearby Starbucks at around noon, and a part of me didn’t want to order anything because I already had a nervous stomach, and had not eaten since the day before. I was, technically, fasting. We talked for a bit but I could tell his mind was elsewhere. Mine was too. Ultimately we went to the hotel, to a private stall, and he began eating my face. I knew, as soon as I entered the room, before he grossly and inexpertly put his mouth over mine, it wasn’t what I wanted. I once again shut down, put on a show; I let him do whatever he wanted to me. When he finished on my face, he was proud he got some onto my clothes. I walked home marked in this way. I also realized I had swallowed some of it. I had not completed the fast.

I spent the holiest day of the Jewish calendar blowing someone I didn’t really like in a bathroom stall. My name would not be inscribed in the Book of Life. I had not repented. I had not apologized for my sins, and even if I did, I was not prepared to start the New Year fresh and free. This dwelled on me for some time. It first appeared to me as comedy, haven broken so many laws and committed so many crimes against God: gayness, breaking the fast, avoiding prayer, having sex out of wedlock, having sex out of reproductive necessity. I was overwhelmed by all that I committed against others but mostly all that I had done, and continue to do, to myself. I felt guilty and ashamed and stupid.

Eventually I felt less of these feelings; they were not replaced by anything else, were not rationalized into nonexistence, but simply dulled with time. I look back at last year with contempt, and despite being a non-observant Jew; I am still plagued by a fear that I have committed the ultimate form of disrespect. I did not atone. I had sinned and sinned again. I had committed self-harm, and had committed self-harm again.

A part of me will always feel this way, burdened by mistakes, unable to move forward, unable to sit down—famished—and reflect. I can’t do Yom Kippur justice. I can’t be sorry in a way that will suit my family, my religion, or the God I was raised to believe in. My apologies to myself unfortunately don’t do much. Often they just magnify the guilt, invite awareness that human behavior cyclical: I’ll constantly put myself in places I shouldn’t put myself in. People will get hurt. I will get hurt.

But another part of me thinks of the flowers, and the heat, and the safety of my childhood home and its floors, and the warmth I have to come to realize I cultivated from within. I think of it as a ball of hot, divine air, spinning like a skater on ice somewhere between my heart and belly. That is what I focus on, what I try to hold close and reflect upon. Hearing that voice is the most sacred, the most sustainable, the most enduring. To again feel that warmth is the most honest way to celebrate a year gone by, a year full of regrets and longing and misplaced desire and the millions of other things that are and always bound to go wrong.

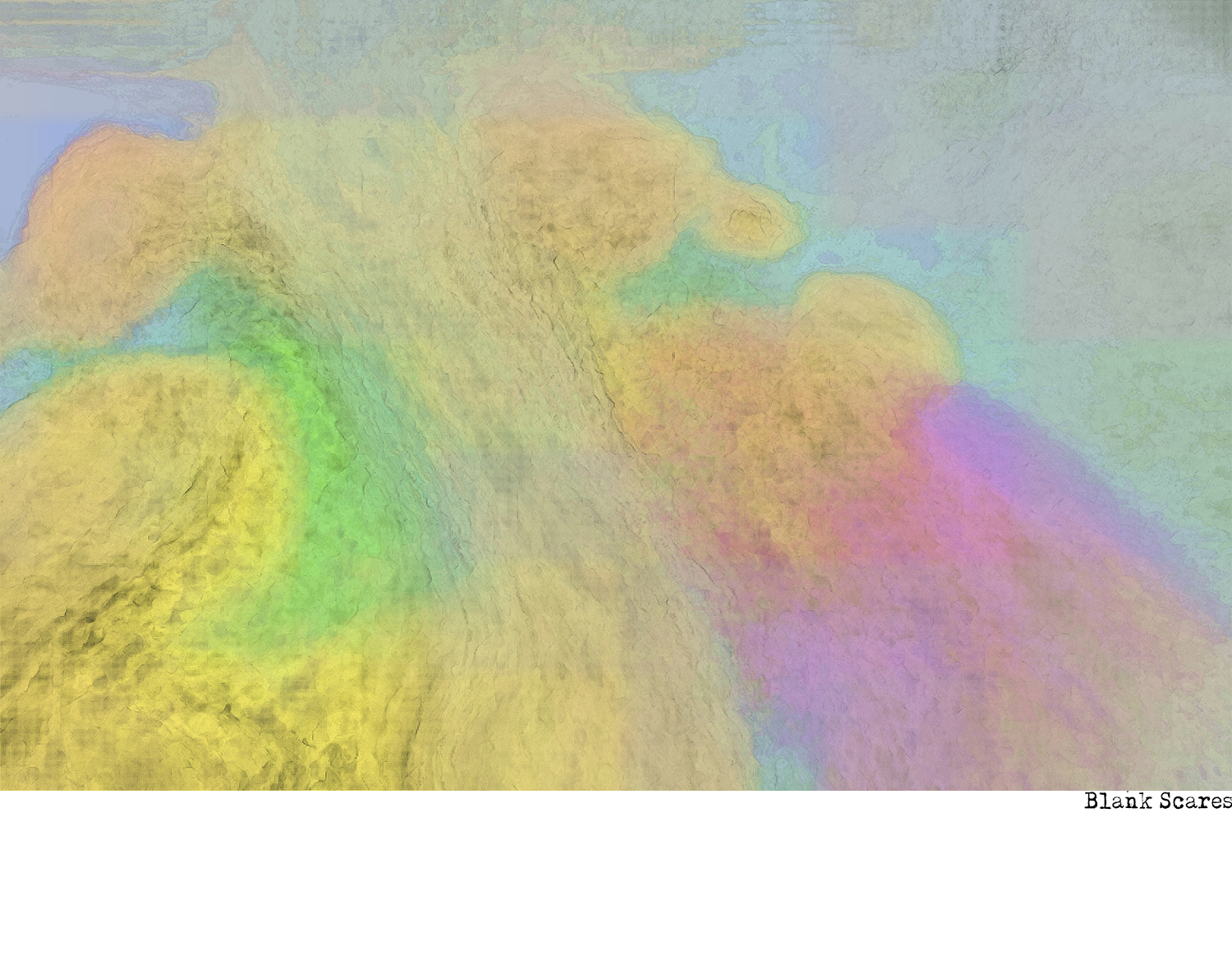

The Official Debut of FATHERS EP /

Artist A.O. Gerber, former singer and songwriter of the New York-based collective, Little Sur, has returned to her native West Coast with a new solo-project: a six-track EP titled, Fathers.

Written mostly in Bennington, Vermont, Fathers is an investigation of identity and selfhood, exploring the often fraught relationships that shape us and the actual and metaphorical fathers that raise us. Gerber recorded, produced and mixed the EP herself.About the album cover: Samuel Burhoe is an artist working in books, installation, and performance. He researches ritual practice, particularly as it relates to community, sacredness, and death. He attended Bennington College in Vermont and is currently baking bread in New Hampshire.

You can also stream the EP here.

turkish baths la fitness /

the warm, wet naked of

doctors, of cousins

of us in the baths

of the big gym on gower

language, we choose.

we assign it to touch-things.

sex is to naked,

as mammary's flesh-lump

as culture's to practice, to practice, to practice.

towel off,

soap up,

soak.

decision

as liquid

as water

on skin.

FIVE: Selected Poems /

Julia Lans Nowak is a poet in Los Angeles, currently completing her MFA in Creative Writing @ the California Institute of the Arts. She is co-organizer of the LA reading series WHAT WERE YOU EXPECTING, a sometimes Polish-English literary translator, a new associate editor for Semiotext(e), a non-practicing musician. Her website isagglutinations.org but it needs an update so she recommends looking at it in like a week.

Her new chapbook American Poems/Unamerican Poems is being published this month by Calico Grounds.

FOUR: Selected Poems /

Julia Lans Nowak is a poet in Los Angeles, currently completing her MFA in Creative Writing @ the California Institute of the Arts. She is co-organizer of the LA reading series WHAT WERE YOU EXPECTING, a sometimes Polish-English literary translator, a new associate editor for Semiotext(e), a non-practicing musician. Her website isagglutinations.org but it needs an update so she recommends looking at it in like a week.

Her new chapbook American Poems/Unamerican Poems is being published this month by Calico Grounds.

THREE: Selected Poems /

Julia Lans Nowak is a poet in Los Angeles, currently completing her MFA in Creative Writing @ the California Institute of the Arts. She is co-organizer of the LA reading series WHAT WERE YOU EXPECTING, a sometimes Polish-English literary translator, a new associate editor for Semiotext(e), a non-practicing musician. Her website isagglutinations.org but it needs an update so she recommends looking at it in like a week.

Her new chapbook American Poems/Unamerican Poems is being published this month by Calico Grounds.

TWO: Selected Poems /

Julia Lans Nowak is a poet in Los Angeles, currently completing her MFA in Creative Writing @ the California Institute of the Arts. She is co-organizer of the LA reading series WHAT WERE YOU EXPECTING, a sometimes Polish-English literary translator, a new associate editor for Semiotext(e), a non-practicing musician. Her website isagglutinations.org but it needs an update so she recommends looking at it in like a week.

Her new chapbook American Poems/Unamerican Poems is being published this month by Calico Grounds.

ONE: Selected Poems /

Julia Lans Nowak is a poet in Los Angeles, currently completing her MFA in Creative Writing @ the California Institute of the Arts. She is co-organizer of the LA reading series WHAT WERE YOU EXPECTING, a sometimes Polish-English literary translator, a new associate editor for Semiotext(e), a non-practicing musician. Her website is agglutinations.org but it needs an update so she recommends looking at it in like a week.

Her new chapbook American Poems/Unamerican Poems is being published this month by Calico Grounds.