The same dust that blew young Ida McCarren into town gutted her father’s 1942 Ford truck overnight. When the storm rose up, tall as the hand of God on the horizon, Mr. McCarren held on longer than you might expect. He made it another mile through the dark wind before he drove the truck, and the family in it, into a deep ditch. When the storm ended, some hours later, men driving past on the way to fill their tanks spotted the Ford, and then they came to pull it out.

It was stripped all over to the rust. In some spots the doors were filed straight through. The crew said they could see the bodies before they walked down the bank. Ida McCarren herself was barely in rags when Bea Garvey swept her out from under the porch, after the storm broke. Naked, but not a scratch on her. No one could explain it, so they called her a miracle because they needed one.

She was real quiet. And they liked her that way. No, they loved her that way. The town was in love with the violence of her quiet. They flocked to it, the way crowds throng around a crash. But ever since Boots McCoy had come last year and killed Old Paul and left again faster than he came, Ida’d been less of a fender bender and more of a three-car pile up with the baby screaming and the mother gone. It’s painful to watch, wrecks like these, but that doesn’t stop anyone. So a deep uneasy had settled into to town to take Boots’ place.

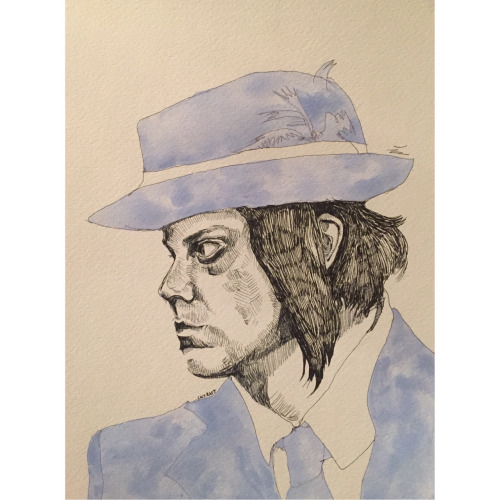

“They told me you were bad news like I didn’t already know,” young Ida whispered to the wanted sign at the post office. Her neck was craned back so far to look at it that the bottom of her chin rested on the wall, just below his mouth, which the sketch artist had got tragically wrong. Mr. Witacher, the postal clerk, was not sure young Ida should be looking at pictures of Boots McCoy like that. He was most definitely sure she shouldn’t go around talking to pieces of paper, so when he went to pick up licorice on his way home he told Bea Garvey to keep a better eye on her girl.

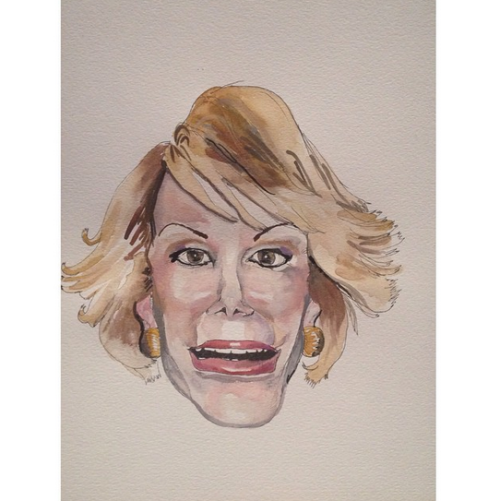

Bea Garvey had taken the girl in after she swept her out from under her porch – she took her in quick - almost before she’d washed the dust off Ida enough to tell what she was. Bea loved distant catastrophes. Bea loved the idea of the storms. Ida is all of these things. She has storm all curled into her young body like an extra intestine. All Bea has to do is look at her and the hairs rise on the back of her neck the way they do when the dust is coming and she hurries to line the windows with rags.

To Bea the dust was a righteous coming, like the flood. She daydreamed sometimes, that she was wife to a new Noah. She dreamt she and him built an underground arc with the hull facing the sky and let the wind bring the dirt and cover them safe. To the Lord looking down on them it would be like peering up through water at the bottom of a boat, And wouldn’t that be a gift to the Lord? to experience looking up at something, for surely that is the only thing the Almighty cannot do.

She said nothing of this to anyone, but sometimes she dreamt it in her sleep too, and sometimes she muttered and young Ida heard.

“One time the storm was coming in and I didn’t get into the house quick enough to miss it. My poor eyes,” Bea likes to tell anyone who will listen, and most who won’t. “They saw the storm set the whole horizon growling. It looked like the hand of God come to scrape the evil from the earth.” And then she shivers, in delight or terror no one knows. Except Ida. And God.

When Boots McCoy had come back to town last year every house locked its doors and put their daughters in the corner. Everyone who had ears had heard about Peter McCoy’s lowdown, no good, nephew, with the face that could make an angel swoon.

Ida, being nobody’s daughter, was right there on the store steps when he walked up. Anyone will tell you how the air itself crackled. They shook their heads and clucked their tongues, how could she have known? Poor little disaster.

“They think I didn’t know what you were,” Ida whispered to the wanted sign. “I knew, I knew, I knew exactly.” She smiled with wide proud teeth. “I have good eyes. It’s just that you kick the dust clean when you walk, and those cheekbone – ooh, they're sharp enough to build a house out on. So I did. And then I stayed a while.”

Boots had told her she wasn’t the kind of miracle they thought she was. That she wasn’t just everybody’s good luck charm – a public thing so worn with wishes the bronze wears green. No, she was a personal miracle - just his - which was good timing because he had some plans to make it big – (or in truth to dig himself out of debt before the sharks dug him six square feet of soil, but that - to him - was not the point).

Old Paul’s garage was at the edge of town. Ida did not go there. She had no reason to. Most every one who had a truck went there but Ida didn’t ride in trucks, at least not any more. Old Paul was a gray green man. Gray for the dust and the age. Green for the money. He sat on the last thing people needed. Aside from food, I suppose. But then some of the farmers would go hungry on the bad weeks in order to buy fuel for the tractors, so you tell me.

Either way you answer, Old Paul had a weakness for peppermint sticks and came to Bea Garvey’s every four days for a new packet. This is the only place Ida would see the gray green man and as she packaged the bright red sticks she used to wonder if, in large part, his taste for the sweets had to do with color. The vibrancy he had lost somewhere in the age and the dust and the money. She wondered if he rubbed the sticks on his skin if there was a chance he might turn brown again.

Times of catastrophe are heaven on earth for the entrepreneur, Boots McCoy told her. Especially one outside the law. And had she been to see those cowboy movies? He wanted to know. And how did she feel about masks and the color black? He had told her the dust bowl was ending and with it, their window of opportunity – the chance to do something big – real big. That’s what he said.

After he left she started walking late at night sometimes. Once she was walking past the wanted sign on the fence post by church. “You can stop looking me like that,” she muttered, glaring at it. She walked five steps past it and then doubled back. “You told me I could have everything and everything was all that I took.” And then she stared at it, waiting for an answer.

When they next storm came puttering up the horizon they went to Old Paul’s because they figured he would be in his cellar, waiting out the dust. They also figured that his garage would have the most money in the town. They figured incorrectly on many things. That isn’t the point. Ida hadn’t been this far out of town since she blew in. When they reached the turn in the road just before Old Paul’s came into view, she saw the ditch.

They just turned the turn, as Boots had said they would and she had expected and then quite unexpectedly there she was, traveled back into the mouth of the mystery. The tragedy that had loosed her. There was the crash, and the dust, and the limbs and the dust, and the teeth and noise and dust and there was her gone, and the family gone, but her gone first.

Then they were inside the garage and Boots and Old Paul were yelling and it didn’t matter and through the window, and across the street from Old Paul’s the ditch yawned open across the road, where they found the truck, and her family in it and she hadn’t been there.

She watched it like a sleeping beast. All that was left alive of it was knocking around in her skull. All that was knocking was that dark miles high hand. A night come too soon and all on fire. The hand of God, Bea said, come to scrape the evil from the earth. She wanted to be that hand. Or at least a digit. She wanted something to scrape.

“I wanted to pull the trigger, you know, just to feel the recoil,” she whispered to Boots’ face. She pressed a guilty forefinger against the rusted nail head until it bled. “So, I did, you know.

“And you were so concerned. It was sweet really. How you fluttered around the body, and breathed too quick for your lungs and warned me I was going jail and then to hell. But I couldn’t go to prison, I had only just begun. I ran my eyes all up and down your face, every plane of it, every room of the home I had built up there, and figured I had a way to keep that house locked up safe now. I turned the gun to my shoulder, pulled that trigger again, and slipped it into your limp hand quick before I fell. I did it. I did it. I know.” She pushed her forehead up against the post and moaned.

“It’s just I knew there was all this gray in his head – Old Paul’s head. There was gray all up in Old Gray Paul’s old gray head. All this dust caught spinning in his skull. I could see it. I had to let it out. Turns out it was a red dust. But that’s not the point.

"The weather’s gotta be left be. The weather’s got to go where it will. That’s the only thing we got left to worship, you know. The only thing. I’m sorry, baby, the only - I’m real sorry. I am. It’s just I have a job to do. I have a storm to keep brewed, without it, where would we be? What new balance would we scramble for? What new power would we bow to? It’s unthinkable.”

Her neck drew back briefly to give her room to giggle. Then she pressed her cheek sharp against his and sighed. “Unthinkable. But the good news is, with your face on every wall, this whole country is my front door.”

Kate Guenther is a millennial living in Brooklyn. She reads a lot and is the reigning foosball champion at that bar around the corner. Ask anyone.