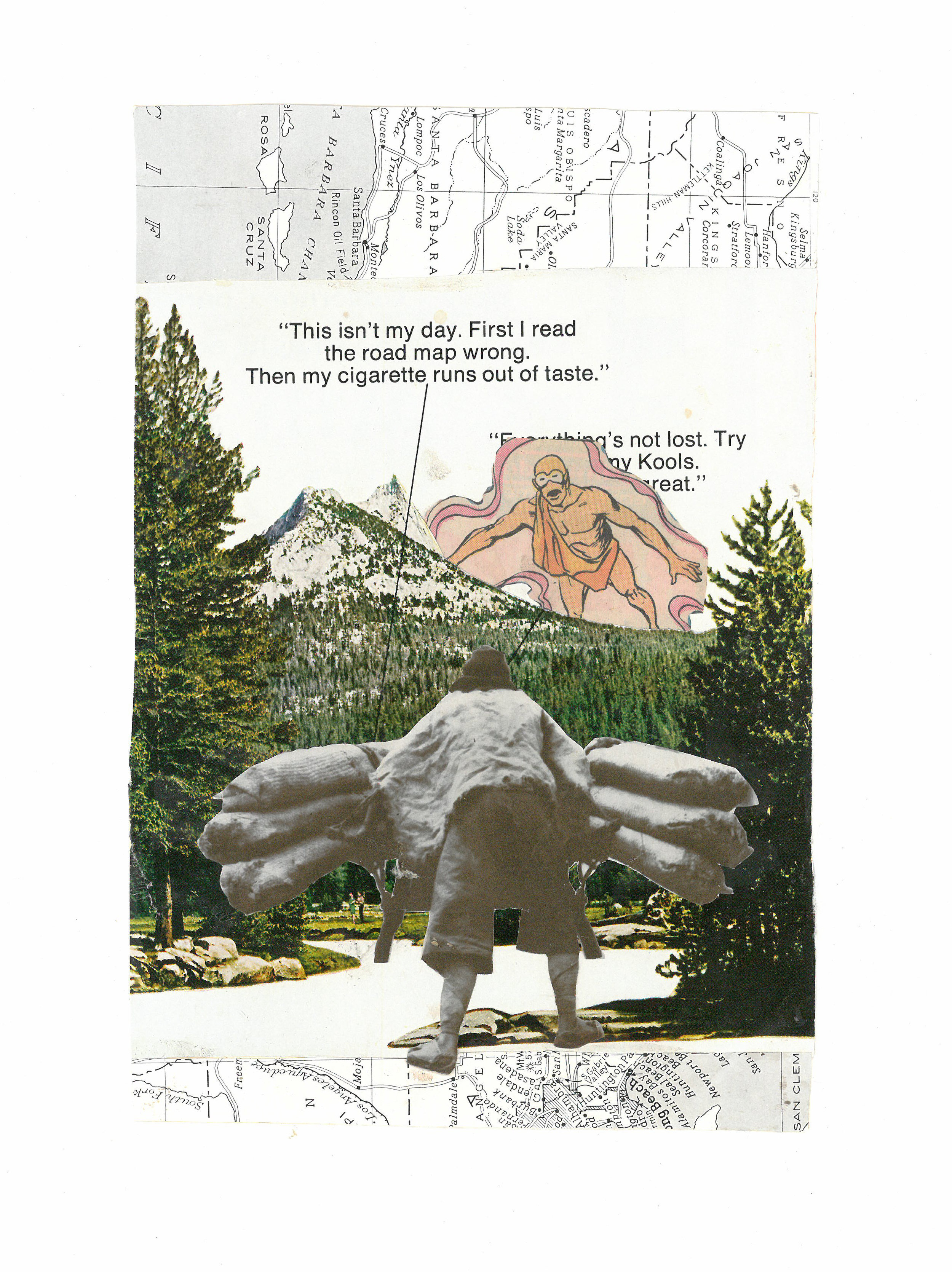

Battling rush hour traffic on his way to Marisa's place in Santa Monica after a rotten day at work, Schecterman couldn't stop thinking about a joke.

Her version: My boyfriend came by with the weight of the world on his shoulders. In the hope of cheering him, I put on mood music and lit candles. Then I opened a bottle of wine and tried to make small talk while serving a lovely dinner. At last he unwound sufficiently so that I could boost his spirits by luring him to bed.

His version: Shitty day at work, then some douche bag nearly plows into me on the way to her place. So what do I get when I finally arrive? Corny music and candles. Then something prissy instead of real food. Least I got laid.

For reasons Schecterman could neither understand nor explain, what Marisa referred to as their relationship remained, in his eyes, a holding pattern, with every aspect qualified by the word enough. It was fun enough, comfortable enough, and at times even sexy enough. Yet rarely did enough feel like enough.

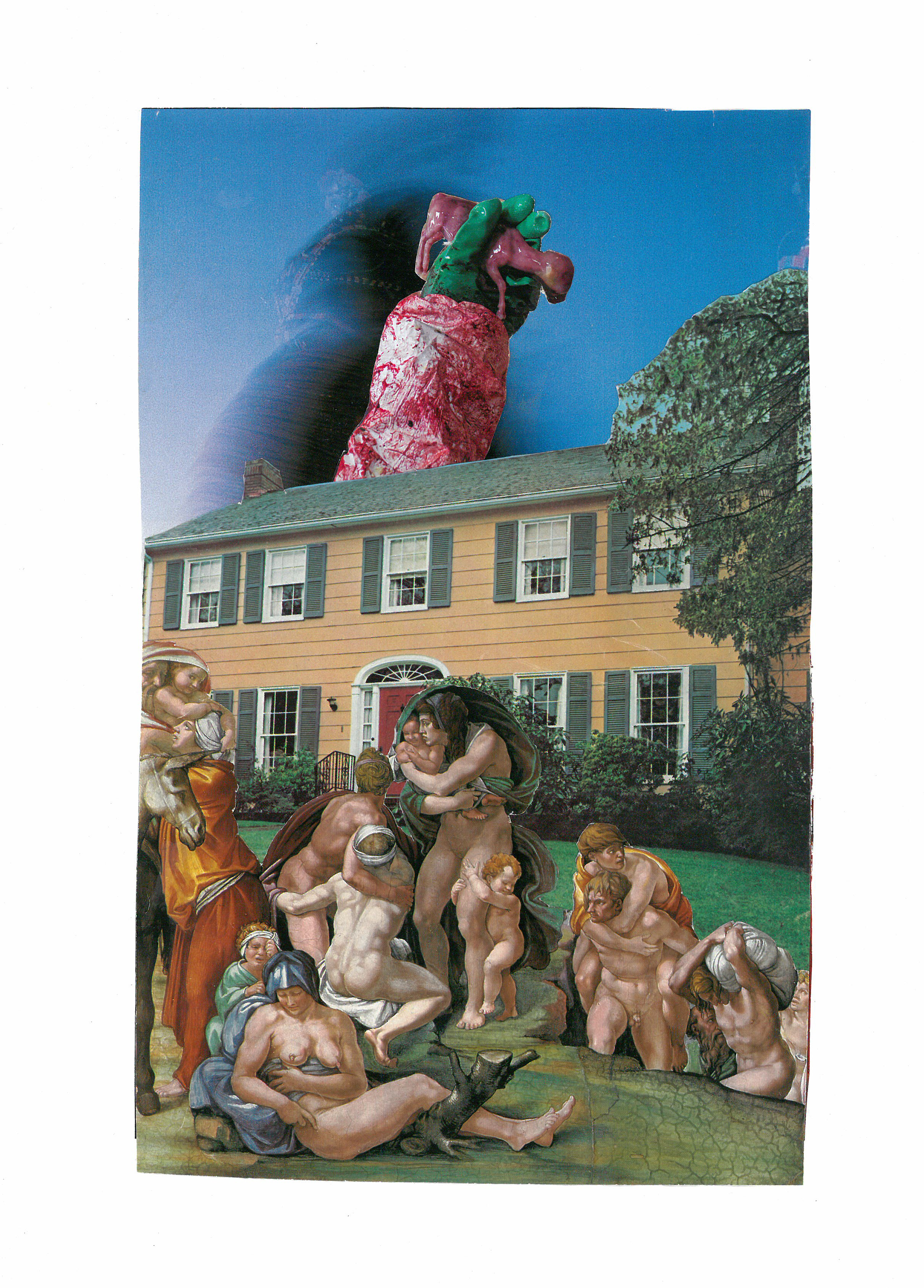

At times – too many times – Schecterman found himself wondering why, almost a year after they started dating, Marisa was still part of his life. Much of it owed to her sense of humor, which continued to surprise him. She could make him laugh by quoting Dorothy Parker (You can lead a whore to culture but you can't make her think). Or by improvizing about Godzilla showing up in her childhood neighborhood in Oakland and getting mugged. Or by putting chopsticks in her mouth like a pair of fangs. Nor did it hurt, thanks to her spinning classes and Pilates, that she was always in great shape. But despite those pluses and others, including a personality far more upbeat than his own, he couldn't quite squelch the sense that the glue, so to speak, between them was either lethargy or a fear of change.

After the break-up of an ill-advised marriage, which unraveled when his wife turned into a hypochondriac who squandered most of her time – and nearly all of their cash – searching for cures for psychosomatic ailments, Schecterman spent time on what he dubbed the bimbo circuit. That meant a whirlwind of would-be actresses, singers, and dancers – plus a magician, and even a ventriloquist – all of whom had, as their primary topic of conversation, themselves.

Next came another well-defined L.A. group: women, as Schecterman put it, who hadn't, as he put it, just fallen off the turnip truck. Closer to his own age, they were excellent company the first couple of times together, waiting until the third or fourth date to reveal their membership in what he termed The Walking Wounded. The common denominators in their tales of woe, Schecterman learned quickly, were two-timing exhusbands, insufficient child support, excessive shrink bills, and, with surprising regularity, messy flings with narcissistic yoga teachers.

Little wonder that Marisa was a welcomed change. Not burdened by obvious neuroses, nor filled with rage against a father, brother, ex-boyfriend or husband, she seemed satisfied with her job as a voice-over agent, free from addictions to pharmaceuticals or alcohol, and not in the least bit beholden to a guru, cult leader, or TV evangelist.

Marisa made no effort to convert Schecterman into a tree-hugger or a meditator, nor did she proselytize a vegan lifestyle. There was no waxing rhapsodic, as was the case with one of her predecessors, about healings, whatever they were, and no attempt to read his aura. Still on the plus side, she never bothered him about conversations with Jesus, or messages emanating from the center of the earth. And on top of that, she was a fastidious recycler, drove a Prius, and shared his affection for a gelateria in Culver City and a Persian ice cream place in Westwood.

The only real problem with Marisa, as Schecterman saw it, was that despite all of her virtues, he was not – and likely never would be – in love with her.

Which made him wonder if he was even capable of love. Certainly he could think of times when he was interested in a woman, or enamored of, or even, as he occasionally phrased it, in lust with. But love? To him was an enigma – something even more alien than the GI Joe gene that was absent from childhood on, or his total lack of interest in opera, the Oscars, or science fiction.

He could be aroused by, turned on by, and even enjoy the company of a woman. But to feel in love as portrayed in films or books or in popular culture? Not with Marisa. And perhaps, he'd come to feel, not with anyone.

That, in moments of introspection, was disturbing, for it made him feel that he was being less than fair. He didn't want to be a stinker who was using Marisa, nor a creep who was taking advantage. But by allowing what he thought of as their situation to continue, he couldn't help but feel that he was creating the impression that it might ultimately be permanent. And that, as he saw it, was not only incorrect, but also selfish.

No matter how awkward, difficult, or painful it might be, it was appropriate, Schecterman decided, to stop denying, and prolonging, the inevitable. He would, at last, tell Marisa the truth: that it was time for both of them to move on.

Hoping that Marisa had simply stopped somewhere for take-out food, Schecterman's heart sunk when she opened the door wearing the apron she donned only when, as she termed it, she felt like fussing.

“Here's my favorite guy!” she chirped, giving him the kind of affectionate hug and kiss that made him feel even worse about the tidings he was bearing. “Thirsty?”

“More or less.”

“Then guess who's got a mojito ready, just the way you like it.”

“You didn't have to.”

“Says who?” asked Marisa with a smile.

Dashing into the kitchen, she returned a moment later with a drink that proved to be just what Schecterman had found on a trip to Havana, unlike the overly sweet concoctions served in far too many local bars.

“I hope you're hungry,” Marisa then added. “But if you're not, I suggest you take a jog or something, because somebody around here cooked up a storm. So if you'll excuse me for a few minutes...”

Fearing that his plans were going up in smoke, Schecterman simply nodded.

Not wanting to be a bad sport, Schecterman refrained from divulging what was on his mind during the Caribbean feast served by Marisa. First came cod fritters with a mango salsa, followed by chicken cooked with red peppers and ripe plantains. So it was only when out came a tres leches cake, plus tiny cups of Cuban coffee, that he stopped procrastinating.

“There's something I've been meaning to say,” Schecterman said softly.

“Me, too,” Marisa replied.

“Really?” he asked, praying that maybe, just maybe, Marisa had reached the same conclusion.

“You go first.”

“No, after you.”

“Sure?”

“Wouldn't have it any other way.”

“Well,” Marisa said, taking a breath, “Okay if I spare us a preamble?”

“Absolutely.”

“So the big news is --”

“Yes?” said Schecterman hopefully.”

“I'm expecting.”

“Expecting w-what?” Schecterman babbled.

“You know what I mean. Happy?”

“More like amazed.”

“How come?”

“You always said you didn't want kids.”

“Until I was ready. Say something, please.”

“I-I don't know what to say.”

“How about 'Wow!'? Or 'Goodie!'? Or even 'Congratulations.'?”

Schecterman studied Marisa for a moment, then rose to his feet. “We talked about this.”

“I know.”

“And both of us said we weren't certain we wanted 'em.”

“Still --”

“And frankly, I thought you were on the pill.”

“I was,” Marisa said with a shrug.

“Was?”

“Up to a point.”

“And then?”

“C'mon on, don't you think it'd be great? And exciting? And wonderful?”

“Marisa --”

“Imagine a kid lucky enough to have the two of us as parents.”

“I-I've got to think about this,” Schecterman said softly.

“What's there to think about?”

“A lot.”

“But what about what you wanted to tell me?”

“It can wait.”

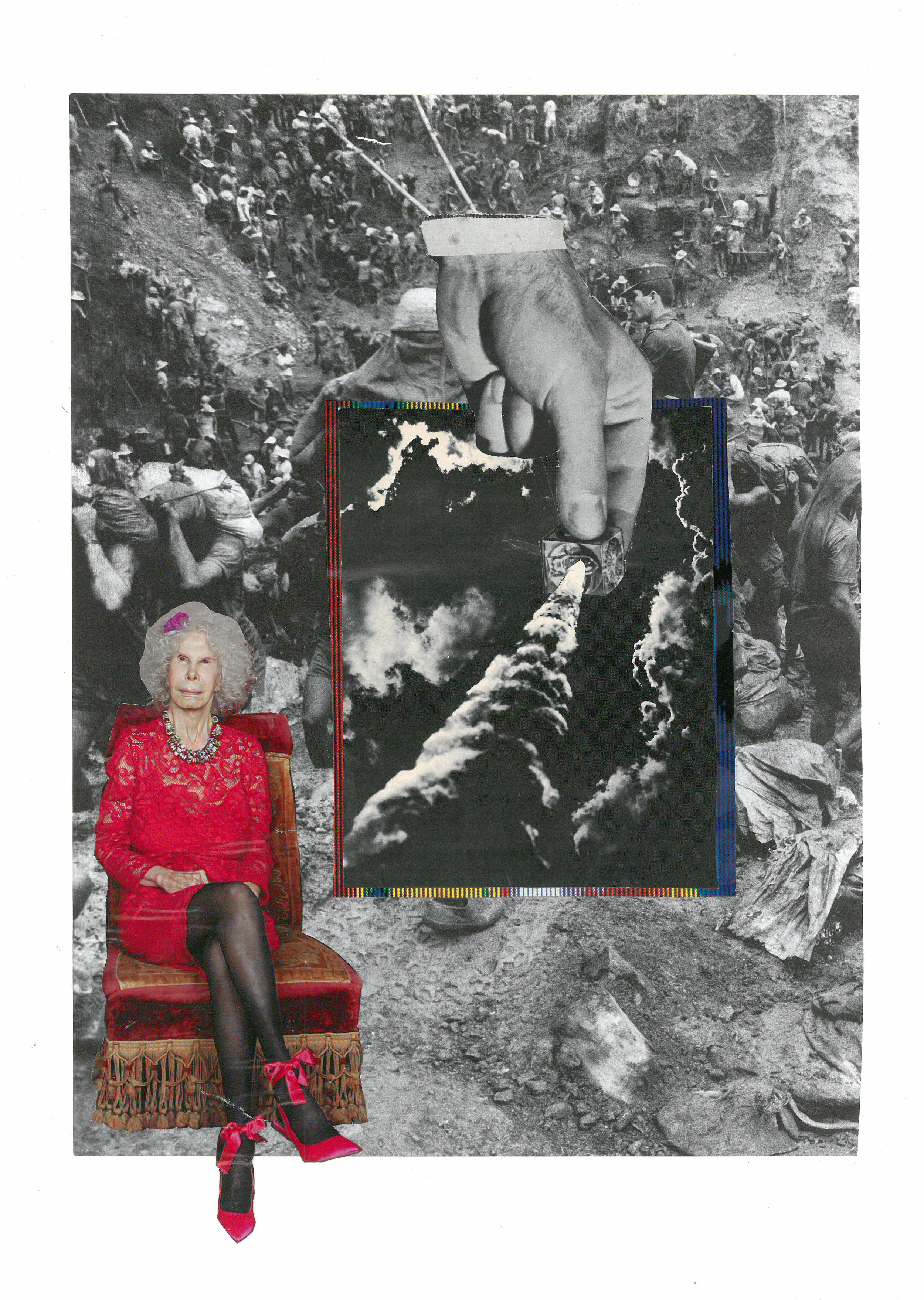

Having heard far too many stories about women tricking their boyfriends into parenthood and marriage, Schecterman found himself thinking of Marisa's revelation as part of a fiendish, gender-specific plot. But then he realized that perfidious behavior was hardly the exclusive domain of womanhood. In fact it was only a month or so before that he had learned, to his dismay, that an ex-boxer he knew had knocked up a girlfriend after feeding her a bogus tale about a vasectomy.

The issue, in truth, had little to do with women, men, or even humanity. Indeed it came down to three simple words – her, as in Marisa... him, as in himself... and them, as in couple – plus the potential for a fourth: family.

Try as he might to justify, or even understand, Marisa's reasoning – that a child might solidify their relationship by figuratively and literally adding new life to it – Schecterman kept hitting a wall.

He was in a state of confusion by the time he got home, torn by conflicting emotions that weren't helped by an hour-long stint on his treadmill, or by downing an overly large snifter of cognac.

A sleepless night, in which Schecterman wrestled with whether Marisa's decision was naïve and optimistic, or simply willful and disingenuous, did little to help his frame of mind. Though he knew the best and most grown-up approach would be to sit face-toface with her and have a calm, rational, grown-up discussion, he feared that doing so prematurely would almost certainly result in acrimony.

So despite Marisa's repeated entreaties by phone, text, and email, it was not until several days later that they met at last, and on neutral turf: the patio of a funky Santa Monica coffee house referred to by Schecterman as the anti-Starbucks.

After several strained attempts at small talk, Schecterman looked Marisa in the eye.

“So,” he said.

“So,” she repeated.

“How do we start?”

“I guess it comes down to whether you've got thoughts. Or ideas. Or best of all, a decision.”

“Seems to me that you're the one who's made the decisions,” Schecterman mumbled.

“How do you figure?”

“Stopping the pill without telling me, then getting pregnant.”

“Seems to me you had a part in it.”

“The act, yes. The decision –?”

“There's such a thing as a tacit choice,” Marisa announced. “I think that has more to do with, say, keeping the same dry cleaner, or going out every Friday for lobster rolls.”

“You've made your point,” Marisa said with uncharacteristic coldness. “So how do we proceed?”

“I won't presume to tell you what to do.”

“That's noble."

“But as for we --”

“Is this a declaration of war?” Marisa asked.

“I beg your pardon --”

“Because if it is, I hope you're fully prepared,” she said icily, displaying a side of herself that Schecterman had never before seen or even imagined.

Subsequent contact came only via email, beginning with a lengthy one that Schecterman sensed had been ghosted by an attorney. Based upon our nearly yearlong intimate relationship, which both of us acknowledged to be exclusive, it began, giving Schecterman such a case of the chills that he turned off his iPad.

Only later in the day did he have the wherewithal to finish reading an epistle that proved to have two objectives. The first, which Schecterman found to be both disappointing and distasteful, was clearly an ultimatum: that he come on-board or else. But it was the second that was even more troubling, since it was without any doubt meant to serve as the prelude to a lawsuit. If you and I can not proceed amicably, it said, I reserve the right to seek all appropriate remedies.

Unable to decide whether Marisa had suddenly changed, or that he simply had not known the real her, Schecterman did his best to put that part of his life out of his mind. Yet no matter how much he immersed himself in his work, taking on assignments on which he might otherwise have passed – promotional work on a documentary about epilepsy that, though well-intentioned, he could never force himself to watch all the way through; a PR campaign for a political group whose stated ideals were far superior to the personalities of the members of the Board – there were thoughts, issues, and questions that couldn't fully be ignored.

How Marisa could possibly believe that extortion would ever reunite them was at the top of Schecterman's list. Next came how she could expect him not to recognize what were clearly attempts to put together a dossier for her lawyer – which is why he made certain to reply to every email with carefully worded rebuttals. Then there was his own role in what had transpired, which led to constant self-examining owing to his total and complete failure to anticipate such a turn of events.

In his moments of anger, confusion, and self-doubt, which were not the least bit abated either by evenings spent with other women, or by the commencement of weekly sessions with a shrink, Schecterman's only solace came from an unlikely source. For years his dream of putting aside P.R. work so as to write a novel had been kept at bay not merely by financial realities, but more importantly by the absence of something crucial: a story that he wanted to tell. But that, thanks to Marisa, seemed no longer to be the case.

Yet while his reveries about down-scaling and at last doing something that was personal, meaningful, and most importantly his, helped buoy him through a trying time, there was still something unavoidable and inescapable that he couldn't deny.

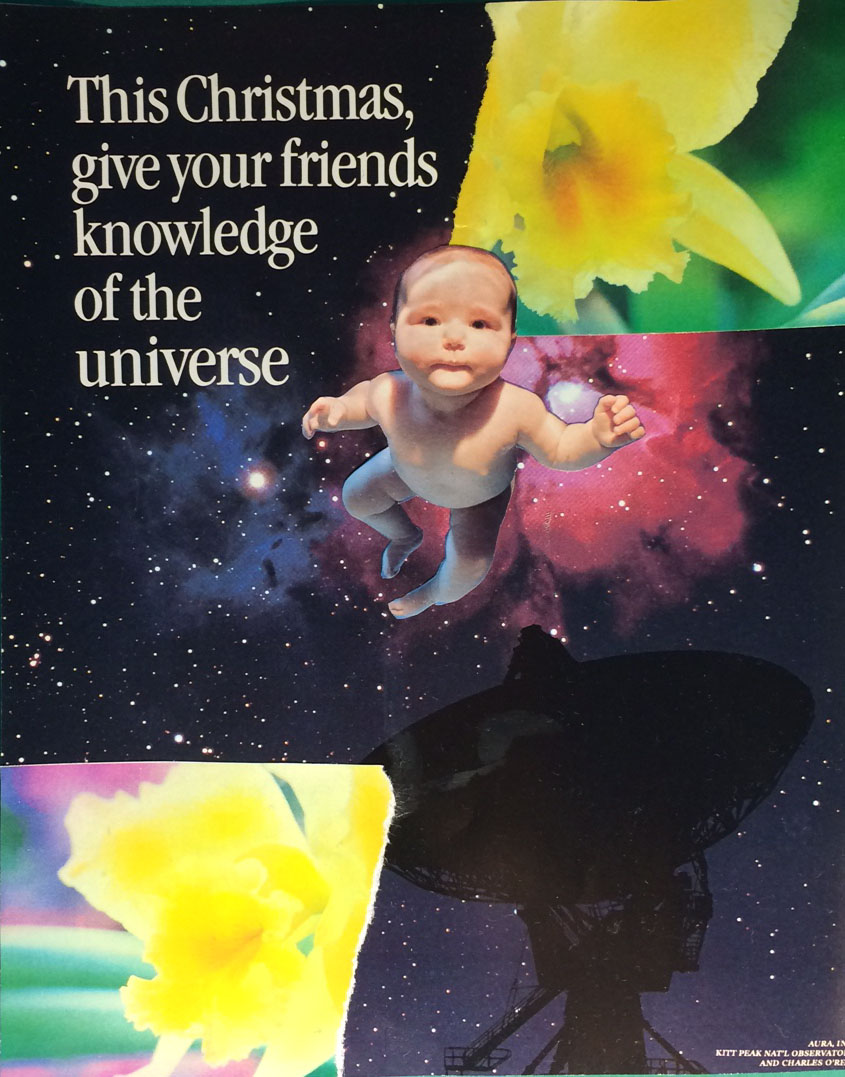

The problem was not, and would never be, simply an issue involving Marisa, or even a potential lawsuit. Far more important was an ever-nearing event: the birth of a baby.

Despite his resentment, rancor, and rage, Schecterman would not – could not – allow his negative feelings to extend to a child. And especially not to one who was his.

Though Marisa's use of the baby as a pawn exceeded Schecterman's definition of dirty pool, he would not, he vowed, let her rage mar a new life. Nor would he let her ruin his relationship with his soon-to-be-born son or daughter.

Retaining a lawyer of his own, Schecterman turned Marisa's demands and threats into a negotiation – one that keyed not merely on her needs, but also on his.

Though Marisa fully expected a girl, it was to a son that she gave birth in late September – one who, from the very beginning, which meant entering the world by peeing all over the place – insisted on things being his way.

Whereas Marisa tried her best to create what she called a gender-free environment – which meant dolls and girly things in addition to cars and trucks – Benjamin, as she named him, found immediate joy not in cuddling, but in breaking things.

Instead of diminishing, the tension between Marisa's realm of Kumbaya and Schecterman's rediscovered boyhood world of rough-housing and pranks, only increased as their son discovered sports.

Initially, that meant an obsession with Nerf baseballs, basketballs, and footballs, plus ballgames watched not just on TV, but also at Dodger Stadium and Staples. Then, as Benny, as he liked to be called, grew older, it meant more and more father-son time. Playing catch and shooting hoops led to participation in local leagues, with Schecterman, drawing upon his jock past often serving as coach, then as Benny grew older, to travel teams, which left Marisa even further in the lurch.

Was that payback? Or punishment? With no certain answer, Schecterman at times found himself wondering.

Rarely, though, did the thoughts linger, since he was having so much fun with the son he never thought he'd have.

In giving of himself, Schecterman found a greater sense of fulfillment than he ever dreamed possible. Did that mean he didn't cringe when Benny had a less than perfect day on the baseball field or the basketball court? Or that he didn't chirp when a ref or ump made a bad call? Or when Marisa grumbled about a game conflicting with an activity she'd planned? Not in the least.

But even as Schecterman found his dream of being a novelist going the same route as his hope of being in love, instead of grumbling about the possibility of a lifetime of public relations, he found himself surprisingly contented with his life.

Alan Swyer is making his living as a filmmaker -- of late, mainly documentaries. His fiction has been appeared in Ireland, England, and in several American publications.