Agnew needs to pay rent. Unfortunately, he's a radio journalist. Unemployed and almost entirely inexperienced, Agnew tries to make up for his shortcomings by being as unprincipled and shamelessly click-baiting as possible. Over 8 “radio bulletins” Agnew reports the most off-beat stories he can find and offers misguided self-help to other aspiring journalists.

***

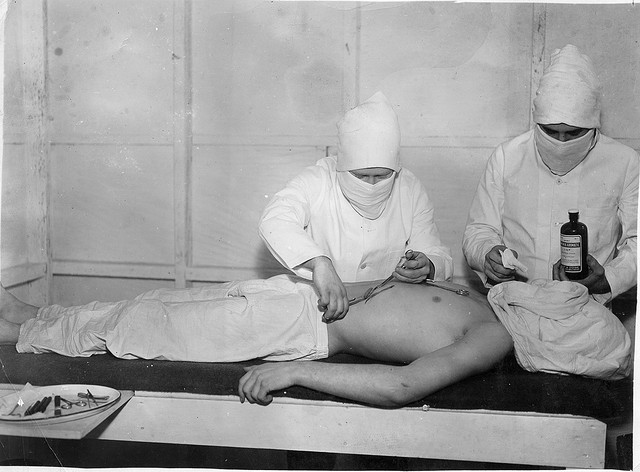

I’m standing once again on the steps of Dr. Drexler’s School of Surgery and Dissection. You listeners may remember my last report from this hall of anatomical study, or at least the great controversy that it caused. It seems the world was not ready for such an honest look at how those who save our lives learn their craft.

Critics decried the scenes I described here as distasteful, gruesome, and journalistically unethical. The manner in which students fetched their cadavers from oversized refrigerators, one listener thought “glib.” That they elbowed for room around the bodies whose lifetimes of hardships were evident in mangled joints and ruined organs, some found to be “too much.” And that I reported young women putting make up on the specimen that used to be Bob Young of N Street and 23rd (who shot himself in the head last year and was only donated to science because his church refused to bury him) may legally constitute “defamation” and “libel.” There was some debate regarding trigger warnings, too.

In any case, several professional associations of broadcasters and radio journalists, to which I formerly belonged, found it to be grounds for “expulsion.”

The impact of my raw reporting on the realities of medical pedagogy was severely negative for everyone involved. (The sole exception being, touchingly, the wife and children of Mr. Young, whose church relented, collected his body, cleaned it up, pieced it together again, and it gave it proper rites in a private ceremony. Private insofar as they threatened to call the police when I showed up.) But unquestionably the worst burnt, and least intended victims of the media firestorm fanned by my fervor for story telling were — no, not the gaggle of corpses from the meth lab explosion — but the very students of Dr. Drexler’s School of Surgery and Dissection.

I have learned that as a result of my story donations of new cadavers have stopped completely. Whereas upon my last visit they were coming in thick and fast, arranged by pigmentation and stacked five by five, cremated en masse at the end of every semester so the school wouldn’t have to run the freezers over break, they now have none.

It is a sad reflection on the state of education today. How will this development affect our nation’s future medical practitioners? Have they begun to rely solely on owl pellets? Will one day, when your heart stops and you’re brought to the emergency room, the surgeon open you up and, out of habit, look for rodent bones? And would he find them? Keep listening.

The corridors are quiet. The operation theaters: empty, but from deep in this old stone building, the familiar voice of the old stony doctor leads me to the storage freezer in the basement. At first glance through the little window in the door, it seems my research may have mislead me. A peculiar room choice, no question, but there the doctor is at the front of it, lecturing on a platform beneath a large angled mirror, one hand in the pocket of his bloodied white coat and the other inside a young man’s head.

He’s naming nerves and digging around the gray matter to find synapses. His students are nodding and taking notes. It doesn’t look so different from my last visit. The smell has even improved; last time I was here, the stench of formaldehyde and carcass reminded me too much of the whiskey I’d been drinking for the last several days and I vomited. Now, there’s no smell at all.

Dr. Drexler spots me in the little window and puts everything back in the young man’s head just as he found it. He reattaches the bit of skull he’d removed with tiny metal plates. One of the students even sews up the scalp and when she’s finished, you wouldn’t know someone had just been poking around beneath it. If nothing else, perhaps their sense of economy has improved.

Dr. Drexler opens the freezer room door. He tells the students to keep working on their labs and shakes my hand. His is gooey.

“Agnew,” he says.

“Dr. Drexler. I hope you don’t mind if I visit?”

“Why would I mind?” He brings me in the freezer and closes the big metal door behind us.

“I heard you’ve fallen on some hard times,” I say and he nods his head.

“It’s true that since your last visit, we’ve had to tighten our belts a bit.” We’re walking through groups of students around operating tables, standing close to each other to keep warm. They’re wearing thermals under their scrubs and I don’t want to get brain goo on my madras blazer. “But we’re making do,” the doctor says.

There are no cadavers, but all of the groups are tearing apart some organ or limb. A grave looking student across the room sees me and uses a detached arm to point me out to her friend. “Yes,” I say, “looks like it.”

“Well thankfully the worst of it is over now,” he says. “The bombs.”

“Bombs?”

“Or little grenades. I don’t know. Didn’t get a chance to see them. Blake tried to look at one though.”

“Oh?”

“And it killed him.”

“Oh my God.”

“Yes,” Dr. Drexler says. “It was the Papists, so there was nothing we could do.” The doctor stops walking and shrugs.

“I don’t understand.”

“But, Agnew,” now he turns to me and takes my shoulders. “Those attacks were the best thing to happen to us.”

“Not for Blake.”

“Yes, Blake, exactly. You see Agnew, we were in quite a position when the bodies stopped coming in. But all of a sudden, we had Blake.”

“You used — ?”

“Of course.”

“And you’re still using Blake? This is all Blake?” I look around at all the students cutting up bits of their former classmate.

“No. Please. That would have never worked. There was hardly anything left. Those bombs were small, but they were powerful,” he says. “Here, I’ll show you.”

Dr. Drexler brings me to an operating table. “Meet Rosie.” It’s the grave looking girl from across the room.

I introduce myself and go to shake her hand but she’s only got one. Her entire right arm is missing. Actually, it's on the operating table in front of us. She had pointed to me with her arm and now calipers are pulling back its skin and fat to expose the bone. Dr. Drexler asks how she is. “I’m good, doctor. I found where I fractured my radius in high school.”

“And it looks like you had some trauma to the elbow too, dear.”

She smiles. “That’s growing up with brothers for you.” Dr. Drexler chuckles sensibly and pats her on the nub.

“Yes, well, be sure your classmates have a look.” She nods. “And any phantom pain?”

“Not yet, but I’m still in shock.”

“Very good, girl. Keep at it.” Dr. Drexler pulls me away from the table and I realize that I’m leaning on the old man.

The students dissecting legs are wearing prosthetics: eyes, eye patches. A pale looking Indian is cutting open what looks to be a kidney and the young man whose head Dr. Drexler was just poking around inside drops some calipers and says “I can’t bend down.” I run to a garbage bin and throw up. It’s full of innards up to my nose. I throw up again. Dr. Drexler pats my back.

“Don’t worry, Agnew,” he says, “we mainly use pig testicles.”

The students are packing their organs and limbs into coolers with ice packs and Dr. Drexler tells me that he’ll be just a minute. He goes back to the platform at the front of the class and says “Excuse me, everyone,” and all the students turn to watch him. “As you know, there’s just one month left in the semester. Hooray.” He waves his finger around and the students laugh. “But, that means you are responsible for your final assignment. In order to demonstrate all you’ve learned this course, I’ll require from each of you a complete dissection and analysis of a human body. You will use your own. It is to be submitted by the end of the term.”

One student starts shouting. “This is too much,” he says. “You’ve gone mad,” and runs out of the freezer without his books. The rest of them accept the assignment like any students would a paper a few pages too long. Some write it down in their notebooks, then climb onto the tables and cut themselves open. Rosie helps the young man whose head was cut open lift his legs onto the table and then climbs onto the one next to him. He holds her incision open for her as she pulls out her liver, lungs, and heart with her only arm.

Some of the students realize that they smoke too much or drink too much, but for the most part they all maintain a medical distance from their subjects as they bleed out and their bodies shut down. A few scream out in pain or cry for the world they’re leaving — the rest roll their eyes at them as they roll to the backs of their heads. Dr. Drexler takes me into the corridor.

“Do you think you have enough for a story, or would you like to come back Agnew?” He helps me up the stairs.

“I’ve seen everything,” I say.

“And do you have any questions for me?” We’re outside his office.

“I mean,” I say, “are you worried about what you’re doing?”

“I am not.”

“The students cutting themselves apart? Killing themselves?”

Dr. Drexler sighs. “Agnew,” he says, “I could have easily starting robbing graves or paying prison wardens or going to the slums or what have you. My profession is no stranger to that. But consider the students.”

“The killed-themselves ones?”

“Yes, exactly. They had a month to complete the assignment, Agnew, but they all arrived at the same conclusion.” He looks at me. “Hm?” he asks and I shake my head. “Why put it off?”

It was a strange visit, but I still make my way down the steps of Dr. Drexler’s with a bit of a hop. I am back on the horse , in some regards. All I need to do now is unload this piece on some chump for two hundred bucks and I’ll be able to mostly pay rent. To get the inside scoop on how to sell a radio spot in The Delph, tune in next week.

***

Nicholas Santalucia is at nicsanta.com.