This is a new ongoing series from Potluck. Every Friday, Ray Belli will provide us with another piece in his puzzle. It's kinda like 'Serial' but not sponsored by MailChimp.

Enjoy!

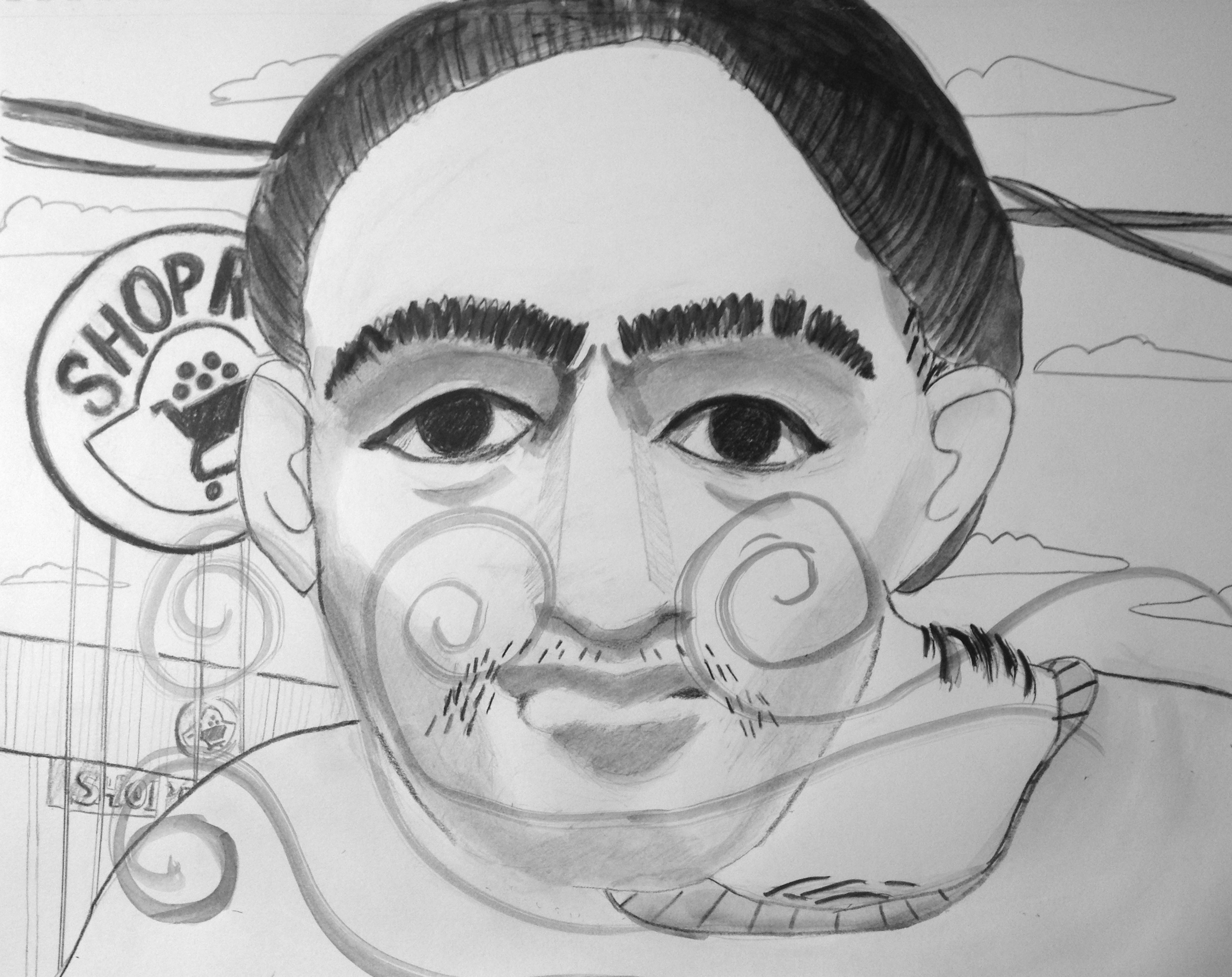

Illustrations by Mariela Napolitano

Time has left the diner alone as far as you can tell. The TV’s still muted, the barstools still creak. For fifty cents you can still have your fortune read by the electronic machine out in the lobby: Squeeze the Joystick and Let Genie Read Your Fortune. As a kid, you found the harder you squeezed, the better your fortune turned out to be. Decade-old fingerprints still blacken the menus. For all you know, the fingerprints are yours. Really, time has left the diner alone—until you open the menu and find that most of the prices have been scratched-out and rewritten by hand. Pen marks have turned “2’s” into “3’s”, “7’s” into “8’s.” Your eyes scan the fine print above the “Breakfast Specials” to see if the complimentary coffee is still included. It is. But in even finer print below the fine print, the words “Maximum: Two” have been scribbled by an unsteady hand.

The waitress reappears, neck jumping, arms jiggling. Still the same after all these years. Like the TV and the barstool and the fortunetelling machine. Time has stood still.

Do you know what you want yet, honeys?

You order the Township Special, no meat, double home fries, and Phillip orders the same with no home fries, double meat.

I’ll be riiiight back with that coffee, the waitress says. Jumping, jiggling. Phillip waits for her to disappear into the kitchen, then wags a finger in your face.

Now you take it easy with that coffee, he says. One sip at a time. Every sip counts.

Phillip Dombrowski, still the same after all these years. Now and then, when time stands still, a good thing can actually become better.

Two cups.

Two fucking cups!

It’s almost as crazy as the metered parking down at Centennial Park, which apparently costs a dollar an hour now. You wonder out loud if Mr. Dewitt paid the parking meter when he’d take Samantha into the front seat of his car to fuck her after softball practice. What was she, seventeen then?

Phillip tugs at his pale blonde moustache, still unconvinced the rumor’s true.

But it is, you insist. Too widespread, no contradictions. Multiple eyewitness accounts. It would have made local headlines soon enough—High School Softball Coach Scores Real Homerun—if Dewitt hadn’t already lost his job for showing up drunk all the time.

The waitress returns with your coffee and sets the saucers down on the table.

First of two, Phillip says.

Excuse me?

First of two. We only get two.

Oh! Yes, there is a limit of two, but—the waitress stops, peers over her shoulder—I’ll get you honeys as much as you want as long as no one’s looking. She butters the end of her sentence with a wink and a smirk.

Phillip lifts his coffee, pinky delicately outstretched. Cheers, he says. Cheers, you say, and coffee leaps carelessly out of the cups onto the placemats.

… to the kind of woman who knows that the rules only apply when someone’s watching.

Mr. DeWitt would be proud, you say.

Phillip shakes his head. Too fat, he says. He remembers: Lunchroom, fourth period, sophomore year. Mr. DeWitt was smiling—no, grinning—under that pencil-perfect goatee of his. See those girls over there? Look at them eat. He blew out his cheeks and went cross-eyed and shoveled one, two, three imaginary forkfuls into his mouth. They try so hard to keep up with the hot girls at track practice. When they run they look like fat little turkeys and I laugh at them behind their backs.

He actually said that?

Actually.

You can’t remember exactly what he called the kids struggling to pass his class—Fucking dummies? Dumbass fuckers?—but what you do remember is the way the corners of his mouth curled up as if aroused when he said it. At the time, none of it seemed wrong because Mr. DeWitt was in fact a good teacher who, on the surface, had everything a small town hero could ask for: Cleverness, athleticism, good looks. Good-looking wife, too. You remember her from a picture on his desk standing arm-in-arm at a Yankees game dressed in matching jerseys wearing matching caps eating matching hotdogs.

Yeah, but that guy has a dark side outside the classroom, Mr. Wilson mentioned in passing. Give him two drinks, that guy becomes a nut.

Wilson and DeWitt were teacher-pals, maybe real-life best friends, but something about Wilson’s remark that day stuck with you. The way he rolled his eyes. The way he sounded like he was beginning to get fed up with something.

… I don’t know, maybe the Samantha rumor is true, Phillip says. The hair above his upper lip is more of a toy for him than a mustache. I remember—

All riiight, honeys, the waitress interrupts. She sets down your plates with a graceless clank and says she’ll be riiight back with some more coffee. Wink, smirk. Jumpjiggle.

You poke the scrambled eggs, stab the plastic home fries. Apparently, time has passed in the kitchen, too. Phillip inspects his lukewarm meat, says he could have done better with a microwave. But you’re hungry and the food’s not as bad as it looks, though the picture on the menu looks nothing like the real thing.

… you know, at least DeWitt never bragged about drinking to seem cool. Do you remember in French class when—?

Phillip nods his head before you finish. Because who wouldn’t remember Mrs. Guenet’s story about blacking out at a college party and waking up the next morning half-naked under a bridge? Murray, Wilson, Adams. The list goes on. You run out of fingers trying to count the number of teachers who voluntarily stopped teaching in the middle of class to share nostalgic stories of their own drunken stupidity. Not just stories, but recommendations for the future too: No, that beer is piss-water. No, that wine’s too sweet. At the time, the stories were exciting and daring and baffled the prudes in class with wide-eyed wonder, but at this point in your life, you can only wonder: Why?

To get their students to respect them as real people, Phillip says. Duh. All the teachers you just named are idiots. You never heard diFranco or Suzuki talking about getting drunk. The only thing that teachers like Guenet or Politti had going for them was a shot at being cool.

By the end of a year with Politti you’d learned nothing about sociology and everything about her hubby—yes, hubby—who had several important business trips to … what’s that country that’s sort of like Africa? With all the beautiful mosaics? Morocco? Yes, Morocco! That’s it! But Ms. Politti? Yes? Morocco is in Africa. Oh? Oh!

—that is not the problem with this town!

An enormous man at the bar slams his fist down on the counter. Beside him, a second enormous man gazes with strained, squinty eyes into the muted TV screen where a news reporter stands outside an old blue door.

Phillip nudges you, pointing at the screen. Is that … ?

The camera shifts point of view to a hallway packed with high school students, then to a close-up interview of a dark-skinned teenager with a nose ring and dreadlocks.

Now that is the problem with this town!

Blocking his enormous mouth with his enormous hand, the enormous man whispers into his enormous friend’s ear. Again an enormous fist comes down on the counter, this time accompanied by enormous phlegmy laughter.

The principal’s face appears on the muted TV screen, mid-interview. She shakes her head Yes, definitely, then No, definitely not, before her mouth abruptly stops moving and she looks like a stumped game show contestant. Her eyes float away from the camera, balloons set free into the air. Her blank eyes blink as her head shakes left to right and the balloons burst into nothingness: No, no, most definitely not.

The camera jumps to a stock image of a school uniform superimposed over a question mark. One by one, bullet points materialize next to the image. You’re too far from the screen to make out the words, but you get the gist. The camera jumps again, this time to a list of test scores. An imaginary marker draws a big red ring around something at the bottom of the list.

Look at that, the enormous man says. Kids in this town can’t even do basic math no more! He pulls out a toothpick from behind his ear and violently works at the notches in his grey-yellow teeth.

His enormous friend raises his enormous hand and calls over the waitress, asking for the check. The men look at each other and their faces become boy-faces, excitable and naughty. Like the dog-kicker, Phillip says. The dog kicker, the nameless kid in elementary school who loved kicking his dog.

Will that be all for you honeys today? the waitress asks, hovering at their tableside.

That’s a great perfume you got on, the enormous friend says.

My perfume? Oh! Thank you, it’s my favorite. An uncertain grin appears on her face, then disappears; appears, disappears.

… so will that be all for you honeys today?

You get our hopes up when you call us that, the enormous man says. He looks at his friend and they laugh together, turning her powder-red cheeks redder. She looks down to hide her flickering grin and burrows through her apron for the check. Grinning, not grinning, grinning, not grinning; jumping, jumpjiggling.

Poor lady, Phillip says. As she passes your table she morphs her grin into the smirk that signifies more coffee, but there’s no turning off the color in her cheeks—or the jumpjiggling.

More coffee? she asks.

I think we’re okay, you say. Phillip nods, and she takes away your dirty dishes, sets down the check. Your eyes follow the enormous men’s eyes following the waitress into the kitchen. The spectacle of her jumpjiggling from behind gets them jumpgiggling.

Back to the lunchroom, fourth period, sophomore year: Look, says Dewitt. He points with his finger and your eyes follow. Dana Minto, jumpjiggling from behind, walks from the lunch table to the garbage can and dumps a greasy cardboard tray into the garbage. See? Fat little turkey.

—damn good turkey!

The enormous man shoves a final piece of meat into his mouth, then indulgently sucks the grease off his fingers. So whadda we got here, eight and six? he says, lifting up the check. That’s fifteen for the two of us.

Fourteen.

Fourteen? The enormous man opens his enormous hand, using his enormous fingers to count.

… thirteen, fourteen—oh, fifteen. You’re right!

The enormous man’s friend counts his money, twice to be sure, then tosses the stack of bills onto the table. He glances up at the clock on the wall. It’s broken, and if you remember correctly, it always has been. He shakes his head and rolls up his sleeve and checks his wristwatch instead: Noon and he’s got to get going. The clock on the wall says half past seven, a stagnant seven stuck still.

I’ll be dead before they fix that thing!

He starts to lift himself out of his seat, slow and heavy like a planet moving through space.

You just reminded me of something, the enormous man says, standing up with the same planetary slowness. His tongue probes his lips for any grease he might have missed. The flesh on his cheeks rumbles from a close-mouthed burp.

The other day I picked up my granddaughter from school, he starts, and this kid in the hallway comes up to me and points to the clock on the wall and says, Tell me what time it is. I can’t tell time. I’m standing there dumbfounded thinking, Ain’t this the saddest thing in the world that a third grader don’t know how to tell time? I go, What’s wrong with you, kid? You’re gonna have to learn to tell time if you ever want to be a man! He says, Sorry, I only tells time on digital clocks. I only tells time. That’s how he said it. The whole time he’s talking real bad like this to me. For God’s sake, what the hell are they teaching kids in school nowadays?

Which beer is piss water, of course, and which wine is too sweet. You scrape up the last bit of yolk with the side of your fork and slide the metal between your teeth. It helps you keep your mouth shut as the enormous men—celestial bodies in orbit, really, minus all the beauty but just as astounding—walk by. Their mouths keep flapping until the door behind them slams shut with a careless bang. A few heads turn, then immediately turn away. A mindless knee-jerk reflex.

… is the real problem with this town, Phillip says, shaking his head slowly.

You ready to get out of here?

Let’s go.

Phillip looks at the check, takes out his wallet, and puts money on the table. Ten and ten is fifteen, he says. You owe twenty.

I think you mean twenty-one.

Oh, right. Sorry.

Phillip goes to the bathroom before leaving, says he’ll meet you outside. You stand up and look around for the waitress. You’d like to say thank you. You’d like to say more than thank you, but as she emerges from the kitchen doors jumping and jiggling with a plate of soggy burritos in hand, all you can do is smile, barely.

Come again soon, honey. I’ll be here waitin’ for you!

And the TV will be muted and the barstools will creak. Genie will be there to tell you your fortune. It will be about half past seven o’ clock.

* * *

The End

Raymond Belli is a professional drummer and writer originally from New Jersey. You can email him at ray1018belli@gmail.com.