This is a new ongoing series from Potluck. Every Friday, Ray Belli will provide us with another piece in his puzzle. It's kinda like 'Serial' but not sponsored by MailChimp.

Enjoy!

Upon Returning Home

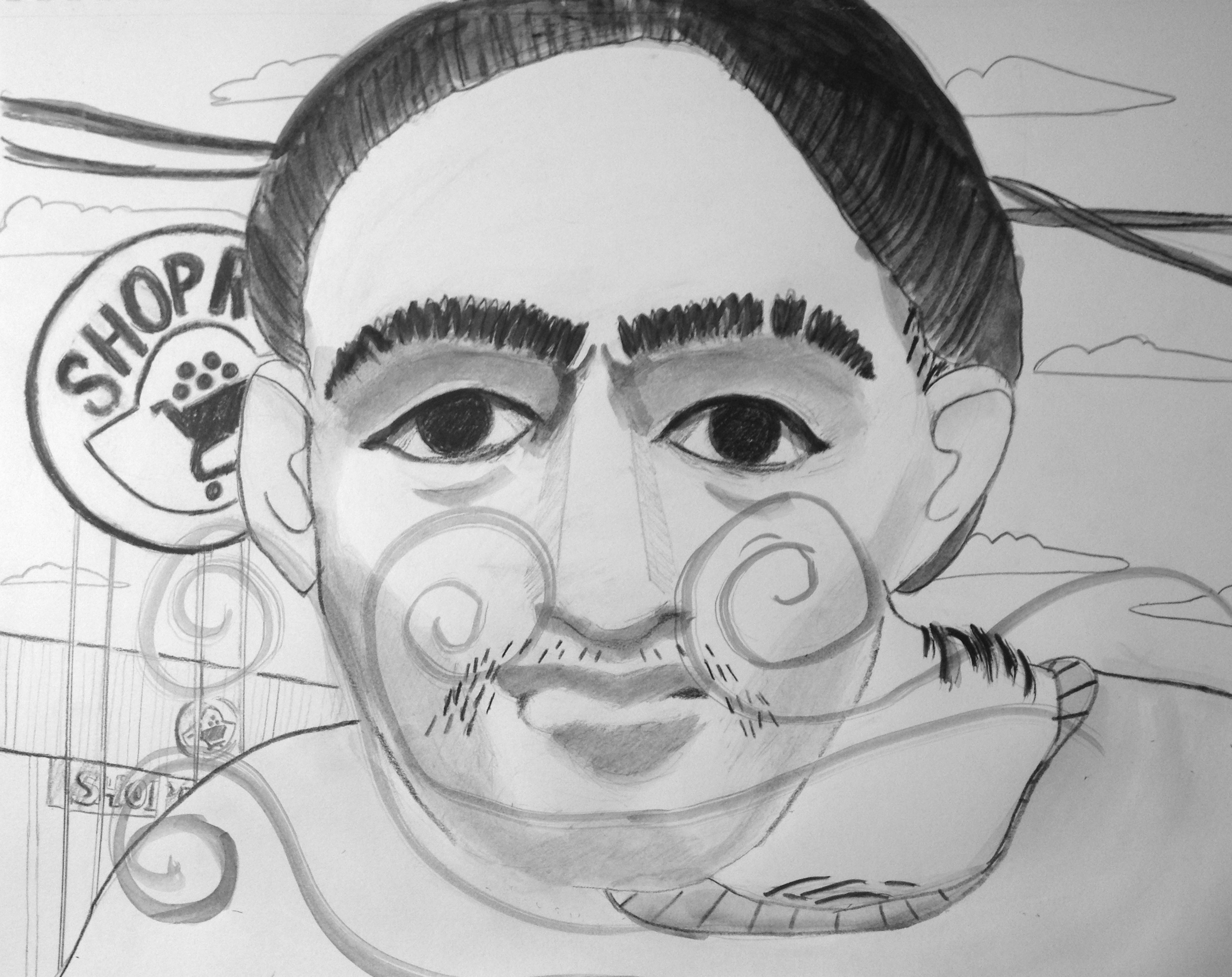

Illustrations by Mariela Napolitano

On the sign on the side of the road where you turn off the highway, then again on the banner that hangs from the bridge that crosses Essex Street: Welcome to Lowe Township. Big, golden letters that assume you’ve never been here before: Welcome to Lowe Township.

But it’s been a while for you and things have changed. Main Street’s changed, the highway’s changed. Ma says the people have changed too. You tell her things are changing all the time, but she says a town like this is never supposed to change. You probably shouldn’t repeat the rest of the things she says.

Jen turns her perfect blue eyes out the passenger’s side window. Tides of cars along the highway. Traffic.

I can’t believe that people sit through that every day, she says.

It’s her first time in this part of New Jersey. You’ve tried explaining that in places like this, it’s the little things that matter—your favorite pizza place, the batting cages, the parks. Jen says that’s how it is everywhere. But everywhere isn’t here, you remind her. Nostalgia, she says, but the truth is that people here give you the feeling that no one else in the world is precisely like them.

And what’s that supposed to get you? That’s her father talking. You met her father once. He had the impression of a person for whom things in life need an objective, material purpose, because everything else is hippie shit and that won’t get you nowhere. You don’t entirely hate him.

You get off the highway at Essex Street and approach Petrillo’s Deli—well, what used to be Petrillo’s Deli. It’s The Korner Store now, and the Grand Opening sign is still hanging off the side of the roof. Jen touches your arm, says she wants to stop for gum. You pull over and get out.

Inside, there’s a program on a small TV in a language you can’t understand. You couldn’t understand when Ol’ Petrillo spoke Italian, but there used to be enough Italians in town that you’d recognize words here and there. Fratelli, fangul, fanabala. That’s mostly what Ma means about people here changing, that families like the Petrillos and Andrettis are moving out. Moving out or dying out.

You hear the bathroom door close and Jen’s gone when you turn around. In the meantime you walk the aisles: rice, cereal, beans, detergent. The man behind the counter—tall and dark and leathery with a mustache and eyes that look like melted berries—stares you down without smiling, without speaking. When Jen comes out, he stares her down too. He keeps on staring until you step outside to leave.

* * *

It’s only for a second that you catch the Redhead throwing punches in the rearview mirror before someone beeps and shouts Move. It’s the echo of her fists slamming into the sandbag that turns Jen’s eyes out the car window. Even at a distance, the punches are loud and clear, short and mean.

Bad day at work, you tease, but the truth is that the Redhead showed up two or three summers ago here in Lowe Township and has been beating the living hell out of that sandbag ever since. No one knows her or where she came from, but of course, everyone knows of her and where she is now. She’s hard to miss on the corner of Main and McKinley with the way she sets that thing up in the middle of her lawn.

Jen gazes into the rearview mirror until the Redhead becomes a tiny speck and a lawnmower drowns out the distant sound of her fists.

Now I’ve seen a punch or two in my day—you remember this from a friend’s father—really, a good punch or two, but never from a young lady that I’d call beautiful. Really, just beautiful. The first time I saw her, I had to drive ’round the block to get another look at her ’cause I couldn’t believe my eyes.

You pause, for effect, and Jen’s face pinches into a small knot as if physically bracing herself for what you’ll say next. For what the Redhead will say next.

She stopped punching and gave this guy the finger, you say. She said if he didn’t get moving she’d shove her sandbag so far up his ass he’d never believe it came from a woman.

The pinched knot loosens and Jen ponders the story, eyes glued to her toes. The eyes stay glued there until you ask what’s wrong.

I bet someone hurt her, Jen finally says. She thinks about it for a few seconds, then nods. Someone hurt her. Physically, I mean.

Huh. Well that’s one theory, you say. Jen is probably right. That sure would explain the sandbag up the ass.

* * *

The door won’t budge, you have no keys, and you’re stuck outside upon returning Home. Ma’s out food shopping and won’t be home for an hour, but the weather is perfect so you take Jen for a walk around town.

She’s regretting it, you think, regretting coming here for the weekend before spending the summer at her parents’ house in rural Pennsylvania. Maybe regretting it puts it harshly. But she’s not used to houses like these, houses side-by-side with fake grass and lawn decorations out front—or sandbags, for that matter. Ma’s house isn’t too shabby, but it’s nothing like Jen’s with a Jacuzzi and a gym and a hardwood floor in every room. Around here, you got Jimmy Feducia to come in and furnish your home with whatever you needed at the friends and family discount. But then they put him in jail for tax evasion, and the business went under after his son tried taking over.

… so the kid tried being a cop, but word on the street is he couldn’t fire a gun to save his life.

And then?

And then, you chuckle. And then he got a job as a clerk at the gun shop on the highway. But now he’s in jail too for smuggling handguns on the black market.

The chuckle hurts because you knew the kid and his dad. You hiked and fished with the kid and his dad. But telling the story to Jen somehow makes it funny.

You put your arm around her waist and start walking.

Welcome to Lowe Township, you say. Welcome to Lowe Township.

* * *

You take the path alongside the river that cuts down to Main Street. A smell drifts up from the water, a smell that wasn’t there when you were young—or maybe it was there and you never noticed. You notice new things about Lowe Township all the time, things you couldn’t have noticed as a kid. Not just the things that Ma complains are changing, but the things that’ve stayed the same. Exactly the same. Girls becoming their mothers, boys becoming their fathers. Patterns of nepotism beginning anew. Again, Jen says, that’s how it is everywhere, and, again, you insist that everywhere isn’t here.

Now you’re being a hypocrite, she says.

What?

You just are. You talk about this place like everyone lives behind a peephole or something. I mean, I get it, sort of, but you take it too far. Everybody lives in the center of their own universe no matter where you go.

The way she says it makes you slow down. You stop altogether. Now that’s a thought: Lowe Township, Center of the Universe—well, their universe. Your universe? You guess that’s where the peephole comes in. But peephole sounds cruel, and it is. Maybe that’s what the look on Jen’s face is for, the look she’s been wearing since you’ve gotten to town. You tell yourself it’s more like a doggie door popping open and closed. Because no one could fit through a peephole, anyway.

* * *

Down on Main Street, crouched over an untied shoelace: That you Jay?

Jay knows the voice and turns. Aw shit, he says. He gives you a knock in the chest, asks what you’re doing back home. The way he talks makes it sound like a big deal.

Visiting my Ma for the weekend, you say. Jay, this is Jen. Jen, Jay.

His eyes roll all over her body. You know exactly what he’s thinking—what she’s thinking.

You a famous rock star yet?

Working on it, Jay.

When I see you on TV, I’m gunna say, I used to know that kid! I used to party with that nigga! When you a millionaire, remember Afro Jay, aight?

And you will. You’re not sure about the millionaire part, but you tell him you’ll never forget the people in Lowe Township, the people you grew up around. He says to watch out for cops nowadays ’cause they don’t care if it’s two grams or two ounces anymore. It’s been three years since you’ve quit, but you say you’ll be careful anyway. Less to explain.

He hoists up his pants, says he’s got to get going. Business, ya know? You expect him to say more, but he’s less enthusiastic than you remember. Droopier, crustier.

When he leaves, Jen asks if that’s what all your friends from around here are like.

Not all. Some. What do you think?

Oh, Jen laughs. He’s great.

But for all you know it’s her father laughing. Jen’s family is used to lawyers, engineers, politicians. Yet Jen’s fallen for you, a musician from a town like this. But that’s not the weird thing. The weird thing is that after living in New York, touring the world, and getting a good start to what you’d like to think of as a career as a professional musician, you like being here in Lowe Township. It is home, whatever that’s worth. You still like to see what happens.

The Morning of Skunk’s Arrest

Jay lived illegally in a single room on the second floor of an old house covered with ivy. Tippity’s mom let him stay there. An extra two hundred a month kept her happy, and no one said a word.

Jay dragged himself into the kitchen for breakfast and noticed a clump of eggs in a pan on the stove. He chased away a fly and poured the cold, hardened egg-stuff onto a plate. Two spoonfuls was enough. His stomach churned, his head throbbed. Everything hurt from last night’s combination of chemicals.

He brought the eggs to Tippity’s door and knocked.

“You want your ma’s leftovers?”

Tippity opened the door. His eyes were heavy and glazed. His shirt was on backwards, inside-out. He stood there silently for a few seconds, then took a step back. The step back was the strange thing.

“Whatsa matter with you?” Jay asked.

Tippity took the plate and set it on his bed. He gazed downward at nothing, half-turned away from Jay.

“They arrested your brother this morning,” he said

“Say what?”

“Yeah. Check your phone, it’s been ringin’ like crazy.” Tippity hesitated, then said, “That’s all I know. But you can’t stay here anymore.”

“What?”

“You heard me.”

Jay’s heart stopped beating. His stomach stopped churning, his head stopped throbbing. Everything stopped completely until his heart kicked back to life.

“I’m sorry, but—”

Jay punched Tippity in the face. Tippity fell backwards into his bed, spilling the eggs onto the floor. He grabbed Jay by the wrists and tried shoving him out of the room, but Jay squirmed loose and punched him again, this time in the side of the head.

“Yo, chill out!” Tippity said.

“I live here,” Jay said.

“Yeah, not any more. Me and my mom live here.”

“I pay you, nigga. You can’t just kick me out.”

“I swear to God, Jay,” Tippity said.

He got up and pressed the back of his hand to his mouth. Blood, red and foamy. He flicked it off his hand and slammed the door shut. Jay violently shook the knob, pounded the wood. Eventually, the sound of a video game resumed on the other side.

“Are you forreal?”

But in less than twenty minutes he was out of the house. In his backpack were some clothes, his laptop, and two ounces of pot that he planned to get rid of by tonight. The TV, the bed, and everything else he used belonged to Tippity’s brother who one day disappeared and never came back.

On the way out Jay threatened to break Tippity’s face if he ever saw him again.

From the window in his room, Tippity watched Jay’s shape shrink down the street. Eventually the shape disappeared. He wondered if kicking Jay out was an overreaction. It was a terrible thing, really. Everyone knew that Jay and Skunk were like family to him, and for precisely that reason, he wanted nothing to do with them.

* * *

It was after their mother overdosed that Jay and Skunk came to Lowe Township. They moved in with their aunt who lived in an old woman’s basement, and for a while things looked like they’d turn out okay. A year later their aunt died of an undiagnosed medical problem. Then the landlord kicked them out.

“ … and it’s what we gotta do now, you hear?”

Skunk was sixteen when he said that. They were down by the river, Jay and Skunk, smoking cigarettes like old friends past their age. As kids, they went down to the river to hang out and get high.

“ … as long as we don’t end up like Dad. We’re gonna quit while we’re ahead.”

And back then, he meant it.

Jay gazed into his reflection in the river now. Desperate black rings clung to his eyes, the eyes themselves stained red with insomnia. The shallow water moved gently, licking the tips of his sneakers. He kicked it.

“… then where’s my fucking money, Jay?”

But Jay never found the money—never had the money, he swore. Skunk had pinned him to the kitchen floor and beaten him over nothing, really. That had changed things. When Skunk left town, it marked the end of something. The start of something, Jay had hoped, but here he was, yet again, at the riverside.

He sat in the dirt, knees to his chest, tugging at a stubborn root. He tried to think about nothing, but all he could think about was Skunk’s face gazing out at the world from behind prison bars. The face resembled his own. It had the same eyes, the same nose. The same stubbornness in the mouth.

He tugged on the root harder and it popped out of the ground. The whole thing was much larger than what shown at the surface. Most of it was buried beneath the ground, gnarled, black, and cancerous. He flung it into the river and it landed upright, lodged between two rocks. It began to sway gently, gracefully even, until the water snapped it in half and carried the broken pieces out of sight.

* * *

Jay emerged from the riverside at the back end of a Shop Rite parking lot. An employee with unkempt hair and a bored-to-death expression was smoking a cigarette a short distance away. His nametag said, “Gerber.”

“Got another boge?” asked Jay.

“Last one,” said Gerber, indicating the cigarette in his hand.

“You the law?” asked Jay.

“Huh?”

“I said are you the law? Like the police.”

Gerber looked down at Jay’s mud-stained knees, then up at his sweat-soaked face. “I’m just out here on a smoke break, man,” he said. Gerber’s face twitched with a smirk. He tapped the nametag on his chest. “I work here.”

“Something funny to you?” asked Jay. “I’ll kill you.”

Unfazed, Gerber drew another smoky breath into his lungs. The smirk was hard to hide away.

“You tell me what’s funny, you piece of shit.”

Jay shoved Gerber against a metal pole, then slammed his fist into the side of the nearest car. He grunted in pain or rage and started walking toward the street.

Gerber bent down and picked up the cigarette that had fallen out of his mouth. He continued smoking calmly. Junkie, he thought. Good-for-nothing dickhead junkie. He felt the smirk crawling back onto his face. The smirk turned into a chuckle, the chuckle into laughter. He couldn’t put his finger on what was so funny. But he supposed it didn’t matter. He stomped out the rest of his cigarette and walked back inside, wondering what the good-for-nothing dickhead junkie could have been doing down there by the river. He supposed that didn’t matter, either.

To Be Continued...

Raymond Belli is a professional drummer and writer originally from New Jersey. You can email him at ray1018belli@gmail.com.