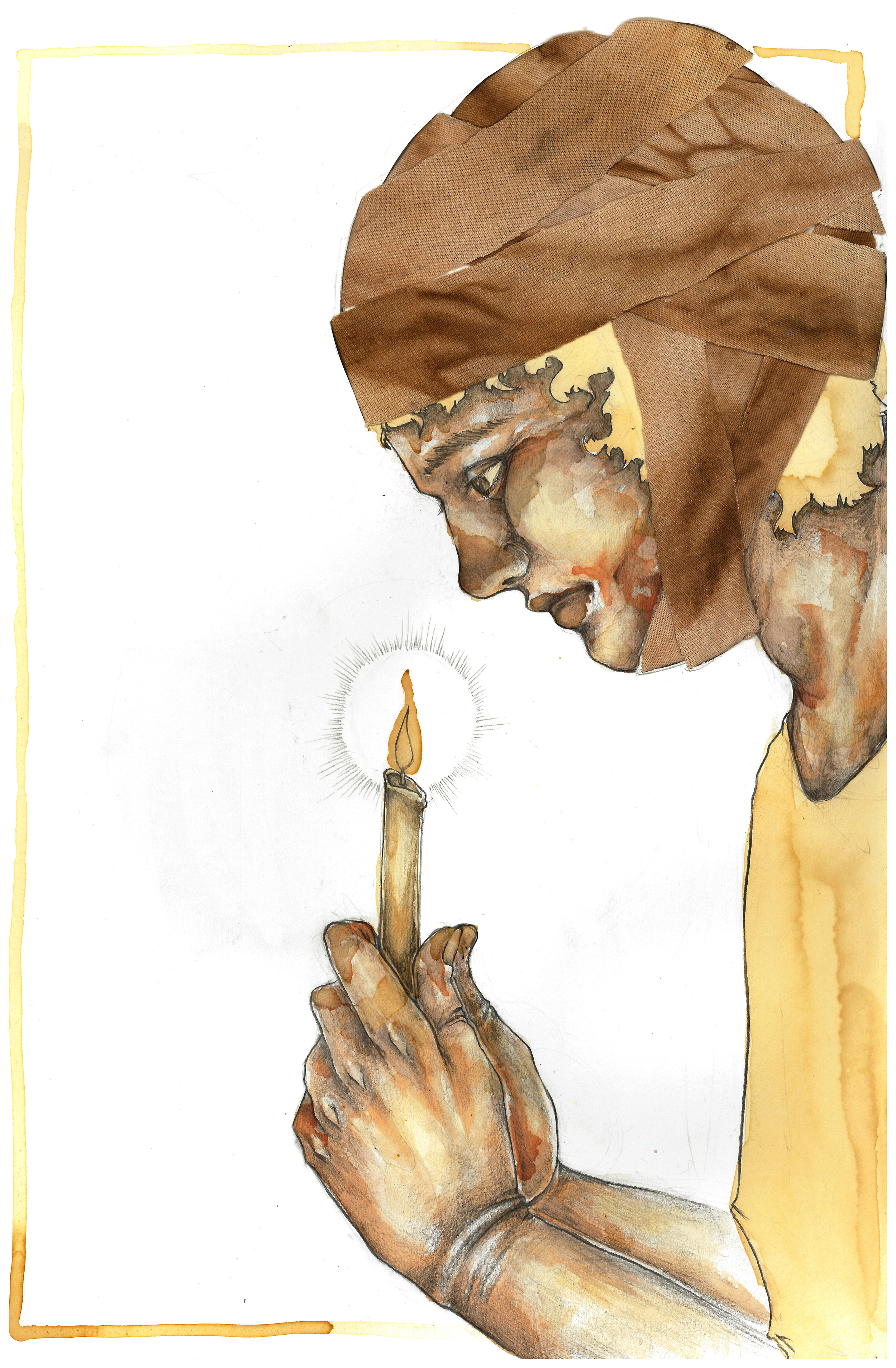

The progression is going to be strange because it’s going to move forward and then it’s going to come back as if nothing had happened in the first place. Remove the idea (the elliptical); we aren’t going anywhere; haven’t been moving. If I have, I don’t know. I’m sure by this point that I’m not much for seeing (can’t do it, can’t bother). In the air of the moment, I realized how little I know. No body, no place, no scene, no set, no company, no eyes, no legs. All I think I’ve got is a mouth; don’t exactly know where to find it, but I’m sure I have it because I’ve constantly been using it. It must be floating around here somewhere; the volume wavers from ear to ear--never really in the similar. What was the word? Yes. I’m without images. I can’t find them. I’ve been without them and so now I’m stuck here listening or trying to listen or pretending to listen and I’m faced with the fact that I’ve been running out of tenses and that I’ve been keeping too loose a grip on the leash and so now I’m practically without language. No. That’s a lie. I have language; I’ve just lost the sense of it; don’t know where to look for it either; don’t know how to move about or look about; just been listening. The objective of it all has been just as loose as I have. But let me try this: I’ve lost a grip on the sense of things and I’d like to find it (don’t like the gibberish, don’t like the gibberish, don’t like the gibberish, don’t like the gibberish). It’s all been flossing my ears and now I feel too clean for it. I have language; I have punctuation. I need for it all to be sensical. I think it’s driven me ill; if I could find a bed around here (my way around here) I’d take to it and stay there forever. That might be the same as I’m doing now. Maybe I wouldn’t be blind if I was in bed (I could look up at my ceiling and all), but then again it wouldn’t matter whether I was blind or not because I’d be in the bed still, and so it in this purgatorial hell it doesn’t much matter whether I’m blind or not. Images lie and beds are bad for backs (would’ve had a back in a bed). Now I’m stuck in a standstill with the language and the punctuation and we’ve been stammering around conversation; they’ve been stammering around conversation. I’m floating about in the abyss of it all, searching for the euphoric side of oblivion, but with company, I don’t think there’s much to find (which is a shame because I’d like to see the way it moves). I can’t see. Right. The language said this to me:

“A word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word is a word.”

I didn’t know the way to reply and so I didn’t. The tone carried along melodically and it went on long enough that it’s all white noise to me now. I don’t recognize (my ears are deaf to it). They aren’t deaf in the whole of things. They’ve been peering about for something outside of three repeated words in an infinite loop indulging themselves. It’s sickening and mundane and one of the few things I’ve been out to avoid. More than that I’d like to meet the speaker if I could because I think it would be a moment for me to see the way that things move about (and they do); we’d say ‘hello’ and ‘hi’ and then part ways and maybe I would see again; maybe he/she/they could introduce me to the sense of it all (because I’ve lost it). If the image is fleeting, put me in oblivion next to any author you like--images of coffee cups and waiters and light conversation. I can still speak (it’s evident). That’s the only way I know how to move along and so it’s the way that I plan to continue. Language continued on; punctuation to explain things to me. It said that the author in oblivion was a modernist and I told it that I’d like to meet him. He isn’t real and so I can’t. The reality of the situation is stuck between language, me, punctuation, and an audience (if any)--moving about in the way it does. At some point I think my mind will disappear. I don’t think I’ll lose my mouth, but my mind might not stay around. I don’t know what I’ll sound like when it happens, but I imagine it’ll be the best part of me. I’ve tried to further my distance (my mind from my mouth); they don’t much like each other; the endeavor of getting them in the same room together would be a nightmare and so I won’t. They can go on ignoring each other, occasionally conversing and agreeing and disagreeing more. And I’ll continue on in the nothingness of whatever a place I’m in. It’ll go on and I’ll listen as my mouth circulates around my body and I’ll look for something good in it all (won’t find it). I’ll look and I’ll find it. Nothing ever moves forward (it’ll all continue in that elliptical circle; moving forward and back and so on; empty as it is). The punctuation heard me and shook me and said:

“..,’.,’,.’,.,’.,’,.’,’.,.’,.’,.,’.,’.,.,.,..,.,.,’.,’.,’,.’,.’,.,’.,’.,’,.,.,’.,’.,.,’.,’,.,..’.,’,.’,.’.,’.’.,.’,.’,’.,.’’.’..’,’.,’.’.’.’.,’..’,’.,.’,’.,’.,’.’.,’.,’.,.’’..’’.’..’,’.’.’’.’.’’’’,’’,..,.,.,.’,.’,.,’.,’.,.,.,..,.,.,’.,’.,’,.’,.’,.,’.,’.,’,.,.,’.,’.,.,’.,’,.,..’.,’,.’,.’.,’.’.,.’,.’,’.,.’’.’..’,’.,’.’.’.’.,’..’,’.,.’,’.,’.,’.’,.’.,’.’.,.’,.’,’.,.’’.’..’,’.,’.’,.’.,’.’.,.’,.’,’.,.’’.’..’,’.,’.’,.’.,’.’.,.’,.’,’.,.’’.’..’,’.,’.’.,’,.’,’.,.’,.’,.,’.,’.,.,..,’,.’,’.,.’,.’,.,’.,’.,.,..,’.,’,.,.’,.’.,.’,’’’.,.,.’,’,.’,.’,’.,’,.,’.,.’’.,’.,.’,’.’.’’’.........,.,.,.,’’’,.,’.,’.,’.,’.,’.,’.,’,.’.,’..’...’,’..’’’.,.’,’,....,’,’.,’.,’,.’,......”

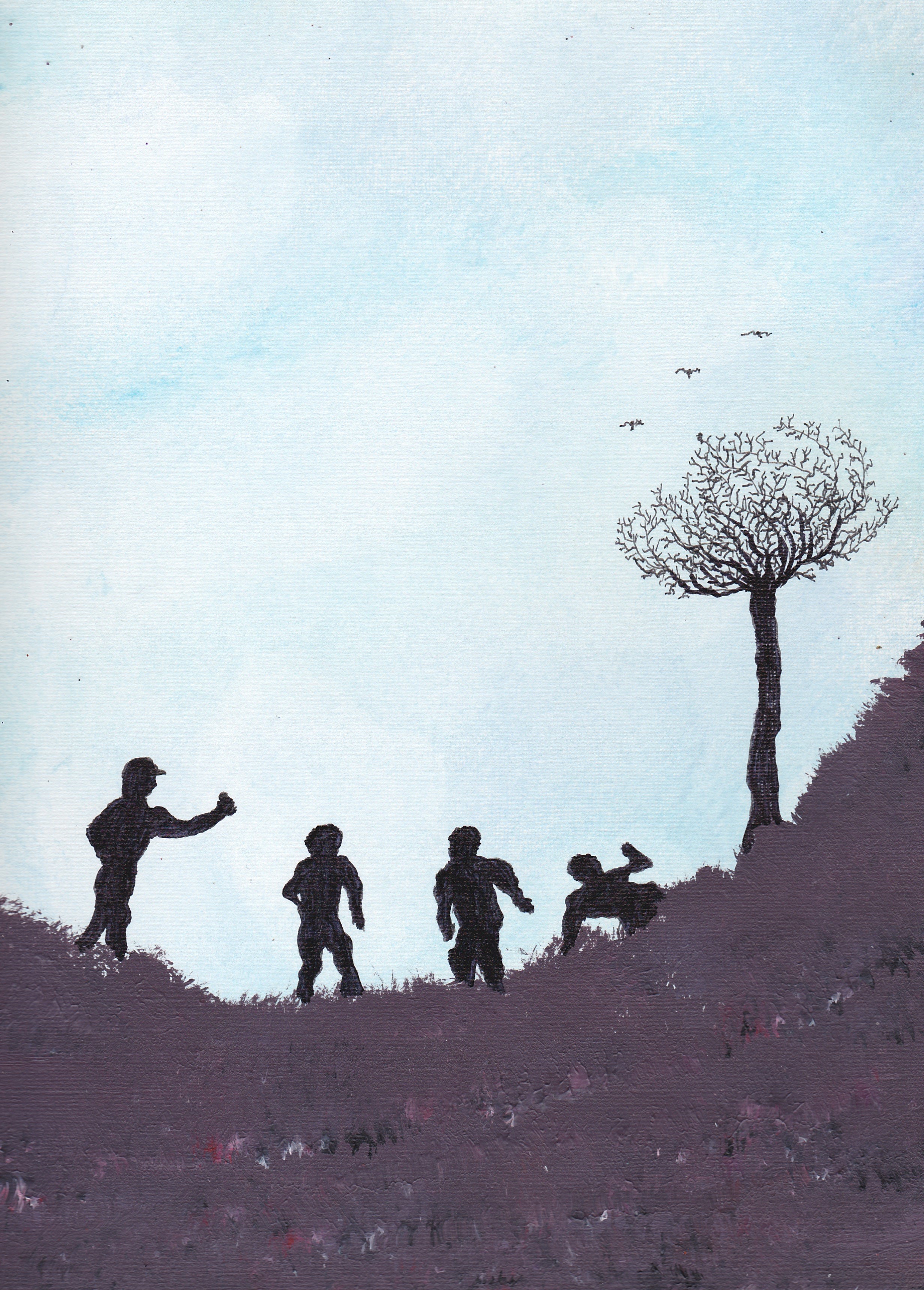

Nothing meant anything and so I didn’t bother listening. The white noise (language and the such) played about still and occasionally I would try to catch it and hold onto it and listen to the words and remember them clearly, but I couldn’t. I let it all go and wandered around without. More than that: the letters are strewn about. Language left them aside and only took the seven or so it needed. If I knew where my feet were, I think I’d be stepping in them. Where has my body gone? It might be strewn about like the letters--limbs littering whatever blackness. Stop. They’d move around, in search of each other (call it a love story; call it spite). They’d find one another and build up to a whole without me and leave. Might have already happened. I haven’t seen them and so they might be gone and I might be alone with the words and the punctuation and the language and the letters and that mouth floating around (also abandoned). I’d be honest and I’d be alright, because it’s the way that things go. Back and forth. They’d be back on the ground again (strewn about) and then they’d be together and then not and repeat. Okay. Now (present tense). What about this (a.): a letter to the author; a question about my whereabouts and their return and if they’d left language alone with nothing much to do but bother us all. Here:

To the author,

I’d like to leave.

Thank you.

I don’t know if I agree with it--don’t know how I’d send it either, don’t know if I would--but I think that it gets the message across. I’ll leave it here (on the page), because I don’t know where I could see myself putting it. Author might of left, might not of. They’ll see it or they won’t and the cycle will move back and forth and it’ll stay still in the average. I’d like to leave (I’m sure I’d say). Maybe when the prose finds its footing and knows where to put me I’ll be more aware (more about). But I’m not and so I don’t think that the prose has any hope for me. We’re stuck alone together, sitting at separate tables on opposing edges of the room, avoiding eye contact. How did we get here? It doesn’t have a purpose to know; I won’t bother (knowing where I am; how to be). Turn around instead (a direction). Take a moment to feel around; I imagined that my eyes were closed and I listened to the silence and smiled (occasionally coming close to that smile, but mostly staying far from it). Sometimes it wasn’t my mouth; I don’t think. It whispered things like Francis or Franny did. It might have been their mouth completely and I might have been borrowing it whenever it came close to me; or maybe it was a shared mouth that changed owners by proximity. And I forget the author (we move back). I’m unsure of how I could leave. Staying here forever is the way that things go; I can tell now and I could tell before and I’m sure I’ll tell in the future; I’ll continue whirling around my tenses, constantly checking statuses. I don’t know how long I can sustain myself for. Soon I’ll be nothing. The thought has been away from me (a bad thing). I’m glad to know now. If my mind and my mouth don’t want anything to do with each other, then let my mind diffuse and I hope the mouth isn’t mine. It would be beautiful and sublime. This: if I had nothing left around me. It wasn’t true though. The author had just left me be for too long. Things have gone out of hand and this is the state we’re in. The language hates me (and I hate it), the punctuation wants nothing to do with either of us and the prose and the letters are all in disarray. We’re all headless (it’s not profound). The prose saw we were alone and said:

“What a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame, what a shame.”

The motifs continued on repeat; the prose hates me; I don’t mind. No one has anything left to do here; we’re all a little upset. Like this: ugh. I’m tired. I’m not sure where to go from here. It’s all exhausting, I feel like I’ve been here for too long and now I’m stuck without any words of my own; I’ve just been picking up piles that’ve already been used--rearranging them when I can manage. This isn’t my dialect (someone else’s). I’m uncomfortable. The goal was what? I can’t remember anymore. It was something useless and so I won’t bother trying to remember what it was. None of this is for me; I’m just resentful now; I’m tired; I don’t have a body, a place, a person, a scene, a set, any of that garbage from back when (whenever). I could leave all of it alone (fade away) and I’d like to. I will. Sorry to put you alone with the language and the words and the letters and the prose and the punctuation, but so it goes. They all said:

“Motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif motif.”

And the trend continued.

Mike Corrao is currently a student at the University of Minnesota where he is studying Film and English. His work can be seen in publications like 365tomorrows, Pop Culture Puke, Century, Ivory Tower, and Thrice.